An unprecedented US$ 1.2 trillion excess of exports over imports is not sustainable

As much as it has been welcomed by its own establishment, China’s mind-boggling trade surplus of US$ 1.2 trillion in 2025 has equally surprised China watchers. For one, the unprecedentedly high net exports have enabled the world’s second largest economy to attain its officially aspired goal of 5 percent economic growth for the year. Equally significantly, the achievement came despite the hiking up of US tariffs on several Chinese imports effected last July. The resilience exhibited was in the face of a host of other challenges and constraints, especially the continuous shrinking of its population and the emerging labour shortage. The number of persons aged 60 years and above, has been rising and by 2035 it is projected to go beyond a staggering 400 million. Their cumulative impact on workforce availability has been perceptible since the retirement age in China, varying between 55 and 60 years, is among the lowest in the world.

The burgeoning exports in areas such as automobiles (especially electric vehicles), batteries and various other renewables, lower grade chips, electronics, and drones reflect the reality that China continues to be the factory of the world. Its manufactured goods still enjoy a high order of competitiveness globally. In the year ending December 2025, its industrial production increased by a notable 5.9 percent. Several analysts around the world have described the strong growth in the production of manufactured goods, together with their exports, as two speed growth.

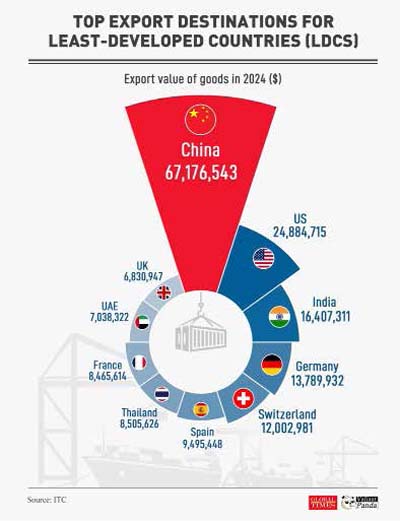

Nations, rich and poor, are finding it difficult to stand up against Chinese prices, as well as the quality, volume and the strict adherence it has to delivery schedules. Consequently, in recent months, more of its manufactured goods found markets ranging from ASEAN to Africa, in addition to Latin America and Europe. As it strives to maintain such a hegemony, particularly in the export of low cost manufactured goods, President Trump’s recent threat to impose another 25 percent penalty, in addition to the existing 47.5 percent tariff, on countries trading with Iran, including China, would undoubtedly intensify its search for new markets.

Nations, rich and poor, are finding it difficult to stand up against Chinese prices, as well as the quality, volume and the strict adherence it has to delivery schedules. Consequently, in recent months, more of its manufactured goods found markets ranging from ASEAN to Africa, in addition to Latin America and Europe. As it strives to maintain such a hegemony, particularly in the export of low cost manufactured goods, President Trump’s recent threat to impose another 25 percent penalty, in addition to the existing 47.5 percent tariff, on countries trading with Iran, including China, would undoubtedly intensify its search for new markets.

An issue of concern regarding Chinese economic growth for some years, has been that despite a respectable full year GDP growth rate of 5 percent, sluggish domestic demand continues to plague the nation of 1.3 billion people. Its Statistics Bureau chief, Kang Lie, admitted last week that “domestically, the contradiction between strong supply and weak demand is pronounced”. Most indicators of domestic demand, from property to retail sales, have remained disappointing. Last December, retail sales, a key measure of consumption, grew by a mere 0.9 percent, the lowest since 2022. This fell short of expectations of 1 percent growth in December alone and 3.7 percent for the full year. Every month until May 2025, when a nationwide programme offering subsidies on cars, solar panels, washing machines and several other white goods was first introduced, and later scrapped for solar panels due to longstanding frictions with Europe, sales had been declining while household savings were edging up. This occurred despite the Chinese leadership making the boosting of domestic demand its top priority. China’s household spending is less than 40 percent of its annual economic output, about 20 percentage points below the global average.

Not only did consumption grow slowly but even the pace of investment declined in 2025. The property industry continues to remain besieged. It has yet to recover from its persistent downturn of almost four years. The country clocked a 17.2 percent fall in property investment last year against a forecast of 16.2 percent. Households continue to store wealth in properties despite their prices declining, as they continually fear further softening. New construction starts also reduced by 20.4 percent year on year. The national fixed asset investment, which includes infrastructure and manufacturing, was lower by 3.8 percent. This was the first full year of contraction since the 1990s and contrasted with a growth of 3.2 percent obtained a year ago.

Unsustainability of the export led Chinese growth

Going forward, the country’s high export growth may not be sustained. The deluge of exports to non-US markets could cause pushback from the affected countries. During a recent visit to Beijing, French President Macron raised the trade issue with his hosts. The European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has also warned that Europe risked becoming a dumping ground for Chinese goods. Mexico has imposed tariffs on imports from China and several well-off countries can be expected to follow suit. To ward off possible allegations of dumping, phasing out the export tax rebate has already begun. This would raise some export prices and dent Chinese shipments. The Chinese leaders are also promising to take other steps to keep trade free and open. Whether this will bring in a rule-based system is yet to be seen. In current geopolitics only allies and friends are being favoured with tariff concessions, and the long followed Most Favoured Nation treatment is being abandoned by most large trading countries.

As revival of fragile domestic demand remains an important priority for 2026 as well, the Chinese authorities can be expected to take a variety of additional measures. Prime Minister Li Quang, speaking on national television last week, called for “proactively expanding imports and promoting the balanced development of imports and exports”. Policymakers will also reinforce their fertility drive, which hit a record low last year with the births of only 7.92 million babies, notably lower than the number of deaths of 11.31 million. Such a decline was for the fourth-year running. Perhaps, it is unsurprising in an environment with rising costs for raising a child, a slowing economy, a property crisis, and high youth unemployment.

As revival of fragile domestic demand remains an important priority for 2026 as well, the Chinese authorities can be expected to take a variety of additional measures. Prime Minister Li Quang, speaking on national television last week, called for “proactively expanding imports and promoting the balanced development of imports and exports”. Policymakers will also reinforce their fertility drive, which hit a record low last year with the births of only 7.92 million babies, notably lower than the number of deaths of 11.31 million. Such a decline was for the fourth-year running. Perhaps, it is unsurprising in an environment with rising costs for raising a child, a slowing economy, a property crisis, and high youth unemployment.

More effectively augmenting the purchasing power in the hands of the young as well as its large middle-class population has the potential to raise the aggregate demand in the Chinese economy. It is also required on grounds of equity for the large number of farmers and rural residents. Alongside this, there is a need to strengthen its weak social security net, to curb high precautionary savings and reduce the average Chinese reticence about spending more freely.

More effectively augmenting the purchasing power in the hands of the young as well as its large middle-class population has the potential to raise the aggregate demand in the Chinese economy. It is also required on grounds of equity for the large number of farmers and rural residents. Alongside this, there is a need to strengthen its weak social security net, to curb high precautionary savings and reduce the average Chinese reticence about spending more freely.

A not-so-inconsiderate fiscal stimulus package would also be required to sustain even the 4.5 percent GDP growth rate targeted for 2026. However, it appears unlikely that Beijing will unleash a major stimulus as it continues to battle with risks tied to local government debt. Also, the top leadership has hinted at a greater tolerance for slower expansion. When growth came in at 4.5 percent in the fourth quarter last year, few heckles were raised within the decision-making establishment.

That said, China’s central bank last week cut sector-specific interest rates and left the door open to further reductions in banks’ cash reserve requirements, as well as broader rate cuts. Action should also be taken to allow the renminbi to appreciate. A stronger currency would lower import costs and help stimulate domestic demand. Another side benefit would be that a transparently valued currency could help its greater acceptance in the world market, an objective China has long aspired for.

Frankly, the Chinese authorities will no longer be able to keep postponing addressing the country’s longstanding structural problem of excess savings. The World Bank and IMF have long urged them to shift towards consumption led growth and rely less on investment and exports, warning that the current model poses long term risks. The K shaped economy has become self-reinforcing and is increasingly difficult to unwind. Much like the post-2007–09 financial crisis response, when a massive domestic property boom was promoted as a temporary fix, only to unravel in recent years, the current push to invest heavily in advanced manufacturing appears similarly myopic. It has the potential to further distort the growth path since the investment building hitherto too has been on construction, machinery and equipment. As such, it cannot be construed as a catalyst capable of turning around the economy. Despite its strong supply lines and the emergence of new sectors, China continues to grapple with unusually weak domestic demand and troubled legacy industries such as property and coal.

The Challenges of Chinese Exports

Such a renewed focus on manufacturing would generate excess capacity, with even higher exports now needing to find additional markets. Its immediate neighbourhood, as well as other developing countries of Africa and Latin America, could continue to provide it with a market for low value added goods. In effect, however, U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports risk undermining the competitiveness of these countries’ own domestic industries by diverting Chinese exports toward them. Chinese mercantilism in the face of American protectionism would thereby cause serious micro as well as macroeconomic difficulties, particularly for small and vulnerable nations. This would manifest itself in multifarious parameters, particularly constrained trade, weakening of currencies and soaring of domestic unemployment.

A degree of economic resilience has been seen recently in parts of Europe and South East Asia, as supply chains get reconfigured, disruptions in rare-earth supplies from China being managed, and jointly developed alternatives gaining ground. These groups of economies are also coordinating efforts to limit the deployment of Chinese technology, especially on security considerations. Chinese technology in several fields – including telecommunication, renewable energy, robotics, drones, batteries, space research and information technology – has undoubtedly come of age. But its tech barons have been compelled to fall in line with the State’s requirements and the wishes of its strongmen, abandoning tech- libertarianism.

A degree of economic resilience has been seen recently in parts of Europe and South East Asia, as supply chains get reconfigured, disruptions in rare-earth supplies from China being managed, and jointly developed alternatives gaining ground. These groups of economies are also coordinating efforts to limit the deployment of Chinese technology, especially on security considerations. Chinese technology in several fields – including telecommunication, renewable energy, robotics, drones, batteries, space research and information technology – has undoubtedly come of age. But its tech barons have been compelled to fall in line with the State’s requirements and the wishes of its strongmen, abandoning tech- libertarianism.

Noticing its increasing preponderance, the EU nations seem to have taken a concerted call to phase these out from their critical infrastructure. No doubt, the cost of completely barring the import of Chinese technology will depend on the availability and pricing of viable alternatives. Simultaneously, as the European Union seeks to also reduce its dependence on technology inflows from the United States, dispensing entirely with the Chinese option may not always work out. The Union has to benignly reckon with the emerging situation where the Chinese manufacturers using hi tech processes have begun to set up their production facilities overseas, nearer the centres of consumption in Europe and Southeast Asia.

While execution will remain nuanced, high risk Chinese suppliers are being identified. Vendors such as Huawei and ZTE are being excluded from the European telecommunication networks, solar energy systems and security scanners. The fragmented national solutions hitherto adopted have been found inadequate to achieve market wide trust and coordination. In recent months, the Brussels headquartered European Commission has launched probes into train manufacturers and wind turbine makers, as well as raided the European offices of security equipment company Nuctech. Since each member nation is in charge of its own security, there may be a degree of asymmetry in the adoption of timelines in the EU for a fuller shift away from Chinese technology.

Nevertheless, the Chinese establishment is already making efforts to market its equipment (particularly the less state of the art technologies) through its efforts such as the Belt and Road Initiative. This seems to be achieving noticeable success with Latin American, African and Central Asian countries. However, this carries the risk of recipient -countries sliding into long-term dependence on China, with potential implications for their economic and security autonomy.

Nevertheless, the Chinese establishment is already making efforts to market its equipment (particularly the less state of the art technologies) through its efforts such as the Belt and Road Initiative. This seems to be achieving noticeable success with Latin American, African and Central Asian countries. However, this carries the risk of recipient -countries sliding into long-term dependence on China, with potential implications for their economic and security autonomy.

As China competes for greater influence vis a vis the United States in Latin America, it is deploying substantial capital and technology in the development of ports, transcontinental railways, and automated construction systems, including unmanned cranes and 5G-enabled infrastructure with both civilian and defence applications. Through such endeavours, it has been able to develop strategic relationships with Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia in South America, as well as with Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia in Southeast Asia. This has not gone down well with the United States, which views Latin America as lying within its traditional sphere of hegemony and regards ASEAN, the world’s fastest-growing economic bloc, as critical to its strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific.

India has to remain vigilant about the continued Chinese thrust on exports. Over the years, it has developed a huge annual trade deficit – driven by ever-increasing imports and near stagnation in exports. At USD 80.2 billion during April–December 2025, this is India’s highest trade deficit with any single country. India imports growing quantities of bulk drugs, especially antibiotics, solar panels, machinery, and fertilisers to support its manufacturing base. By modifying existing restrictions and allowing more Chinese investment in these sectors, none of which pose any significant security concerns, India could reduce its dependence. The rapidly expanding Indian market should, in any case, be of considerable interest to Chinese investors. At the same time, greater diversification of import sources is essential. Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, labour-surplus economies that are rapidly adopting modern manufacturing technologies, should be consciously developed as substitutes. All are ASEAN members with trade pacts with India, and logistics costs for imports from these countries are also competitive.

Another positive sign is that emerging labour scarcity and rising wage costs are compelling China to open up its borders to labour-intensive imports. This has helped India to marginally increase exports of shrimps, electronic components such as printed circuit boards and mobile-phone parts, as well as certain petrochemical feedstocks like naphtha. Going forward, these exports must increasingly shift towards processed and higher value-added products, while also becoming more broad-based to include items from India’s traditional export basket.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ajay Dua is a Former Secretary in the government of India, serving in the IAS for 37 years. A graduate of St. Stephen’s College, he obtained a MSC (Econ) degree from London School of Economics. With diplomas in Business Administration, Marketing Management and Russian Language, he has been on several boards of leading MNCs in India and also the Indian corporate sector. He writes regularly in national media.

Ajay Dua is a Former Secretary in the government of India, serving in the IAS for 37 years. A graduate of St. Stephen’s College, he obtained a MSC (Econ) degree from London School of Economics. With diplomas in Business Administration, Marketing Management and Russian Language, he has been on several boards of leading MNCs in India and also the Indian corporate sector. He writes regularly in national media.