India’s macroeconomic fundamentals remain robust, with strong GDP growth, improving corporate earnings, healthy tax collections, and resilient domestic demand. A strong macroeconomy positively impacts the currency. But it needs no clairvoyance to perceive that it is not the sole determinant. Exchange rates reflect a far more complex interplay of global factors (capital flows, interest rate differentials, commodity prices, and risk sentiment) and domestic variables rather than growth momentum alone.

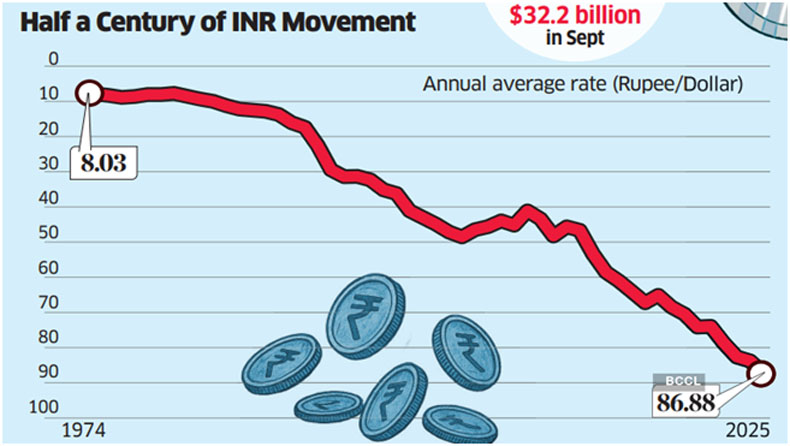

Despite India’s favourable economic trajectory, the rupee has come under pressure. The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) data shows the REER index dipping from an all-time high of 108.1 in November 2024 to 97.5 in October 2025. The exchange rate policy has to adjust to this reality. In the past year, the rupee has fallen 5.6 per cent, from 84.7 to 89.7, against the US dollar.

This weakening reflects several global forces, particularly higher U.S. interest rates, which have pulled capital back into dollar-denominated assets. As U.S. Treasury yields rise, investors rebalance portfolios toward the dollar, triggering outflows from emerging markets like India.

Compounding this, India’s dependence on imported commodities, especially crude oil, creates persistent demand for dollars. Elevated global oil prices widen the trade deficit and put downward pressure on the currency. Geopolitical uncertainties, delays in the US–India trade deal, and episodes of global risk aversion push funds into “safe-haven” currencies, most notably the U.S. dollar, further weakening emerging market currencies. These dynamics, individually and collectively, widen India’s trade deficit and exacerbate currency pressures, even amidst domestic economic strength.

Correlation Between a Strong Economy and a Strong Currency

The relationship between economic strength and currency strength is neither linear nor is there a one-to-one correspondence between a strong economy and a strong currency. While a healthy economy can support a currency over the medium term, exchange rates are primarily financial variables, influenced by capital flows, investment returns, and global risk sentiment.

Several factors explain this disconnect:

- High Import Dependence:

India relies heavily on imports of crude oil, electronics, machinery, and gold. Strong growth increases domestic demand, and consequently, dollar demand, leading to a widening trade deficit. - Interest Rate Differentials:

Even with strong growth, if domestic interest rates are lower relative to the U.S. or other advanced economies, foreign investors may seek higher returns abroad, causing capital outflows. - Inflation Differentials:

Higher domestic inflation compared to trading partners can erode the rupee’s competitiveness over time, contributing to gradual depreciation. - Current Account Dynamics:

Persistent current account deficits put sustained downward pressure on the currency over the long run.

Thus, currencies reflect global capital movements, investor psychology, competitiveness, and balance-of-payments conditions, not GDP growth in isolation.

Rupee’s Fall – Causative Factors

The rupee’s fall, as indeed in the past, is driven more by global factors. Historically, rupee weakness tends to be in sync with a strong U.S. dollar cycle. India’s currency movement is predominantly shaped by global factors, and the current phase of depreciation aligns with historical patterns.

Major global drivers include:

- Strong U.S. Dollar Cycle:

Fed rate hikes or expectations thereof strengthen the dollar and weaken emerging market currencies. - Global Risk-Aversion Episodes:

Geopolitical tensions, financial market volatility, and uncertainty lead investors toward safe assets, prompting capital flight from emerging markets. - High Global Commodity and Oil Prices:

India is disproportionately impacted due to its large crude import bill. Every $10 per barrel increase in oil prices adds billions to India’s import burden.

Domestic factors, viz., inflation, fiscal deficits, and uneven export performance, aggravate pressure but usually act as amplifiers rather than primary triggers. The dominant forces behind rupee depreciation remain global financial conditions and commodity-price movements.

Why Doesn’t the RBI Intervene More Aggressively?

It is not always realised, much less felt, that India’s sizeable forex reserves are not intended to defend a fixed rupee level. The RBI across time periods, Governments and Governors, has consistently (with some exceptions) focused on ensuring orderly movements, not on enforcing a specific exchange rate. Key considerations include:

- Reserves Are for Stability, Not Fixation:

Using reserves to “fight the market” when the dollar is globally strong can be counterproductive and unsustainable. - Avoiding Speculative Attacks:

If markets sense that the RBI is defending a specific level, speculators may target that level, forcing the central bank to burn reserves quickly—an undesirable outcome. - Export Competitiveness:

A moderately weaker rupee improves export competitiveness and supports sectors like IT, textiles, pharmaceuticals, and engineering. - Orderly Adjustment:

The RBI prefers a gradual, non-disruptive depreciation to avoid volatility spikes that could destabilize markets or import-dependent sectors. - Policy Coordination:

Forex markets, monetary policy, and liquidity management must move in sync. Aggressive intervention could distort these dynamics.

In this kind of macroeconomic setting – a setting over which the RBI has little control- heavy intervention is risky because no central bank can conceivably sustainably counter a strong global dollar cycle. Empirical cross-country evidence clearly reveals that “leaning against the wind” does not often work, in fact, mostly it doesn’t. Since a gradually weaker currency also boosts exports, the RBI mainly aims to reduce volatility rather than stop depreciation altogether. Over-defending the rupee can backfire if markets believe the RBI will defend a particular level, speculators may target it aggressively, making it an exercise in futility. Hence, the RBI intervenes selectively.

Rupee Weakening and the Common Man (Aam Aadmi)

A depreciating rupee has mixed consequences for households, businesses, and specific sections of society. Some such negative impacts include imported goods, e.g., electronics, appliances, cars, medicines, becoming costlier; foreign travel and overseas education getting more expensive; fuel prices rising indirectly since India largely imports crude oil; and spiralling inflation due to pricier imports.

The people hit hard are students studying abroad, international travellers, import-dependent businesses, and consumers of imported products. The weakening of the Rupee has, however, a positive or neutral effect on IT and outsourcing professionals with dollar-denominated earnings, exporters (textiles, pharma, software) gain competitiveness, and NRI remittances become more valuable in rupee terms.

Pathway to the Future

In sum, there are diverse forces and factors playing out in the economy today. For the average consumer, the impact is noticeable, but manageable unless the rupee undergoes sharp, disorderly, or prolonged depreciation.

Over the long haul, there are reasons for concern, but not for alarm, because India’s current account, excluding gold imports, posted a $7.8 billion surplus in Q2FY26, strong reserves and surplus, a dovish Fed outlook and the return of equity flows. Elara Capital’s report highlighted a historical pattern in which equity flows tend to return one to two quarters after the REER bottoms out. The rupee is now the most undervalued it has been since October 2018, based on a 40-country REER index. Elara expects this pattern to repeat as domestic growth picks up through mid-2026 and foreign investors turn positive again. Clearly, then, looking at the future with a sense of trepidation is not called for. This too shall pass!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma is Chief Economist, Infomerics, India. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 250 publications and six books. His views have been cited in the Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma is Chief Economist, Infomerics, India. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 250 publications and six books. His views have been cited in the Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.