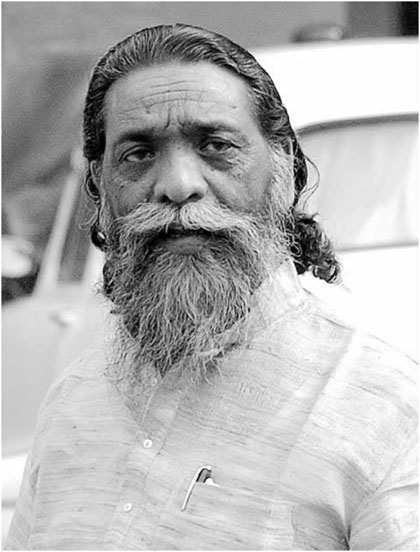

Shibu Soren, the founder and architect of the state of Jharkhand, has moved on. Revered as the Dishom Guru (“the great leader” in Santhali), he leaves a towering legacy of mainstreaming tribal identity and rights, grassroots politics centred on the marginalised communities, and social justice. Despite his turbulent political career, marred with controversies and court cases, his death has left a profound void in the idea of people-centric politics.

As the new millennium dawned, the then NDA government, led by PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, heeded Jharkhand Mukti Morcha’s (JMM) sustained pressure, bifurcating Bihar into two states, Bihar and Jharkhand. Bihar’s state government, led by Lalu Yadav’s RJD, bitterly contested the idea, fearing a downsizing of their political clout, and losing 14 Lok Sabha seats to Jharkhand. Also at stake were cities like Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Bokaro, the nerve centres of India’s steel and coal production, and a source of steady income for an impoverished state. Carving out new states from larger states based on regional identity, language and culture to accommodate varying aspirations has been a striking feature of the Indian Republic.

But Jharkhand was special!

Why?

It was a first when a central government created a large state to accommodate tribal identity.

Jharkhand!

A three-decade-long tribal struggle for self-determination culminated in a landmark political feat. It was not merely a geographical rearrangement but a resounding assertion of tribal identity and rights – and the architect of this tectonic shift was Shibu Soren. Soren was one of India’s tallest tribal leaders. Period. His three-decades-long efforts to mainstream tribal identity and rights, grassroots empowerment and mobilisation and social justice, defined his enduring and unmatched political legacy, making him the poster child for subaltern politics.

But his legacy was equally scarred by controversies and allegations of murders and wrongdoing. While the courts absolved him of these charges, they damaged his public and political perception, repeatedly impacting his fortunes, forcing him to step down as the chief minister of Jharkhand and later as a union minister. Without these controversies to stifle his rise, he may even have occupied the highest office of the land. Who knows? He surely checked all boxes.

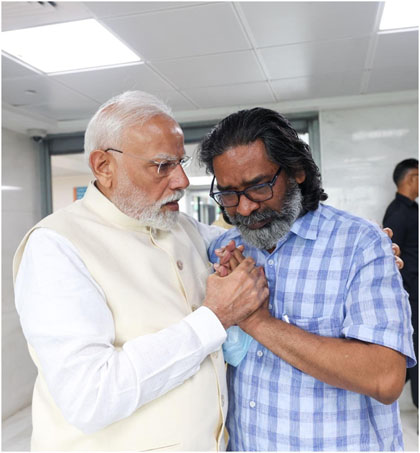

He breathed his last recently, moving on at a ripe age of 81 due to health complications. His passing away led to an outpouring of grief, especially in his home state where he remains the most popular leader, behind only Birsa Munda, a legendary freedom fighter, tribal leader, and a folk hero from the Munda tribe. Leaders across the political aisle paid their respects, led by PM Modi, who visited the Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in the capital to console a visibly emotional Hemant Soren, Shibu Soren’s son and Jharkhand’s current chief minister, calling senior Soren a “grassroots leader.”

A Meteoric Rise

A Meteoric Rise

Shibu Soren did not come from a family of influence or plenty. On the contrary, he lost his father, Shobaran Soren in 1957, when he was only 15 years old. His father was allegedly murdered by moneylenders. This grave injustice and the lack of legal support left an indelible mark on a young Soren. In the early 1970s, he co-founded the JMM with A.K. Roy, a prominent Marxist trade union leader and Binod Bihari Mahato, a lawyer and social reformer.

The JMM was a political party and a social movement dedicated to addressing the aspirations and demands of the neglected and oppressed tribal communities of southern Bihar, now Jharkhand. The JMM organized Santhals and other tribal groups against the moneylenders and landlords who ran rampant in eastern India, attracting the attention of the masses and gaining tremendous popularity. They focussed on highlighting the alienation of the local tribals from their own land, owing to mining and industrialization, by outsiders or “dikus”.

The JMM often resorted to a “shock and awe” style of political activism like harvesting crops on others’ land or cutting government-planted teak trees to reclaim forest land for cultivation, bringing them in conflict with law but endearing them to the locals as they touched a raw nerve. This catapulted Shibu Soren into a league of his own.

Political Journey

Despite failing in his first Lok Sabha election in 1977, where he contested as an independent, he tasted success soon, winning the 1980 Lok Sabha election by defeating the Indian National Congress’s candidate by a slender margin of 3,513 votes. Since then, he won repeatedly in 1989, 1991, 1996, 2004, 2009, and 2014, turning the Dumka constituency into a JMM stronghold, serving as a Lok Sabha MP an impressive eight times. His winning streak came to a halt in 2019, when BJP’s Nalin Soren defeated him by a margin of 45,000 votes, bringing the curtains down on an illustrious political career, spanning five decades and three short stints as a union minister for coal.

Soren was also elected to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house, twice, first in 2002, where he served briefly until 2004. He was a sitting Rajya Sabha MP at the time of his death. While he braved several allegations, his conviction in a murder case involving his former private secretary, Shashinath Jha, in November 2006, sealed his fate, virtually ending his direct stakes in national politics. Even as the courts absolved him, his political capital had diminished significantly.

A legacy Bar None!

A legacy Bar None!

How do you define Shibu Soren’s legacy? A tribal leader? A political organiser? A grassroots mobilizer? A champion political activist whose ideas resonated with a vast majority of the neglected populace of south Bihar? A wily politician who managed to maintain his sway over Jharkhand by bargaining hard with both the BJP and Congress, ensuring that the reins of the state remained with the Soren family, much like other family-run enterprises across Indian states that champion socialist policies and Bahujan ideals?

Most of these are true. However, it is equally true that Bihar in the 1970s was in the grip of a social order perpetuated for ages, where tribal communities had little say in matters of politics or resource distribution. And they were not accorded the rights as enshrined in the Constitution. Soren was able to tap into this vacuum and bring together such communities at the margins of society into a political force to reckon with! His playbook of identity-based politics was widely copied elsewhere with suitable tweaks. Case in point: Mamata Banerjee’s “Maa, Mati, Manush” campaign that dislodged the Left from West Bengal.

The reverberations of Soren’s politics were felt beyond Jharkhand. Jharkhand’s formation catapulted tribal politics from a local matter to a subject of national importance, also reigniting the debate around statehood and the need for smaller states based on practical considerations. Somewhere, it also altered the centre-state relationship, as Jharkhand controlled a massive share of national mineral resources, giving the newly-carved state considerable bargaining power and political importance.

Soren was an old breed of politician whose powers lied not in tweets or Instagram posts but his ability to genuinely connect with the most disenfranchised masses, who lacked education and access to information. He managed to amplify his voice and ideals without any technology or mediums of communication, relying purely on his people connect. Not many boast of such skills. Political activism is a necessary aspect of democratic governance. His brand of politics is waning, and Soren was a master of what is now a dying craft!