Postcolonial India has presented its interlocutors with an existential paradox: on: the one hand, it is considered a rich country in terms of the extraordinary abundance and diversity of its tangible and intangible cultural resources, but on the other, because of endemic rural poverty and its many deleterious consequences, it is bracketed among the poor countries, ‘under-developed’, ‘developing’, ‘Third-World’, in the woke parlance of political economists. During the more than seven decades of planned development and governance after Independence, the government has been alert to the significance of preserving one and modernising the other, but has failed to erase the paradox.

Nevertheless, the country has developed quite remarkably during this period, particularly in terms of its political economy and urban infrastructure. To many it seemed that the country had overcome the stigma of poverty, but it was at the cost of the steady attrition of its heritage legacy and the unconscionable repudiation of the moral significance of Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy to uplift rural India. This has added new meanings to the old paradox, but its significance has seldom motivated policy-makers to critically interrogate it.

However, in a democratic polity, political and social reformers have for long responded to these failings by initiating alternate strategies that are an integral part of India’s development narrative; social scientists in several disciplines have also made their academic contributions by publishing thoughtfully studies that have thrown light on the development that has taken place. These initiatives should have given pause to decision-makers because, in sum, their message was that notwithstanding the growth of the GDP, the historic social, economic and spatial inequities were increasing, particularly between the urban and rural hinterlands, and eviscerating the redemptive promises of Independence. Today, the complexities of old problems are being compounded due to the influence of climate change, and natural and man-made disasters, thus putting to question the quotidian paradigms of development and modernisation that are being followed.

The need for questioning these paradigms, and finding appropriate answers, underpins the rationale for the present conference. While it does not engage with the political economy as a whole, it focuses on the proposition that to upend the enduring paradox that continues to plague contemporary India, it is necessary to link the imperatives of heritage conservation and rural development. More specifically, it proposes to throw light on an important blind spot in the cultural imagination of contemporary Indian body politic by focusing on the future of the unprotected, often undiscovered, Buddhist heritage in rural areas, to explore this proposition to ameliorate rural welfare.

In the routine, it may find little support among government decision-makers and it may also well be opposed by the nascent profession of modern heritage conservation practitioners. Their respective proponents are beginning to find their place on the high table of developed countries, which they would be loath to abandon. The objectives of the conference are, however, not to challenge their achievements but to pick up the slack by focusing on what gets left behind, and thus contribute to the commonweal.

In the routine, it may find little support among government decision-makers and it may also well be opposed by the nascent profession of modern heritage conservation practitioners. Their respective proponents are beginning to find their place on the high table of developed countries, which they would be loath to abandon. The objectives of the conference are, however, not to challenge their achievements but to pick up the slack by focusing on what gets left behind, and thus contribute to the commonweal.

The major lessons that one can draw from the persistence of the paradox is that the problems of post-Independence governance are uniquely complex and require unique solutions to resolve; the mainstream, ‘universal’ ideas of development and modernisation were not sufficient to address the unique challenges posed by a transforming traditional society like India. The overwhelming characteristics of diversity that define India need to be viewed as opportunities, not as problems to be erased to reimagine a future that is more inclusive – socially, economically and environmentally. The objectives of the conference further propose that these insight needs to be purposefully developed by establishing a new Academy that will innovatively engage with the ground realities of rural India in order to explore the potentials of using heritage as a catalyst for development.

In hindsight, one can identify the many ineluctable reasons for the persistence of the paradox. For instance, during the early decades after Independence, there was never enough resources to meet even the essential needs for social welfare and economic development, so sectoral allocations for heritage preservation and rural development were routinely sidelined; typically, they were the last to be funded but the first to be pruned. These sectors were also considered ‘unproductive’ in development terms, and so funding them, it was believed, could be deferred until conditions improved, and in the meantime, hoping that what “trickled-down” would suffice.

These were contingent rationalization, but they had a profound, and long-term impact on the culture of not only governance but the public imagination as well. It consolidated two deleterious beliefs, one, that the imperatives of conserving heritage were opposed to development, and two, the lazy assumption, that it was possible to develop and modernise the nation by following the same well-documented strategies as the West. Faith in these beliefs provided the anodyne to rationalise the loss of the country’s rich cultural and rural legacies.

The genealogy of both beliefs was seldom questioned. The fact that it was rooted in the instrumental nature of colonial practices of conserving the country’s iconic historic monuments and constructing new buildings and settlements to serve their imperial purposes would have cast a different light on these beliefs. For instance, it deliberately ignored the significance of understanding and using the local context to conserve historic buildings or construct new ones, because colonial initiatives were predicated on their innate belief in the superiority of their civilizational values and practices, and by their moral and aesthetic aversion to the attributes of Indian civilization. These egregious attitudes have insidiously seeped into the culture of post-independence governance and stained both the strategies of development and the public imagination, thus giving new meaning to the old paradox.

Not only have these colonial legacies taken toll on the country’s cultural and rural resources, but it has also hollowed-out its potential to imaginatively mediate the processes of modernisation by developing a more organic engagement with the past, present and future. This loss was sustained by the administrative protocols that compartmentalised the sectoral components of development into separate verticals – economic, infrastructure, environmental, cultural, etc., – which made it difficult to introduce inter-departmental and inter-disciplinary practices to pursue reforms.

Not only have these colonial legacies taken toll on the country’s cultural and rural resources, but it has also hollowed-out its potential to imaginatively mediate the processes of modernisation by developing a more organic engagement with the past, present and future. This loss was sustained by the administrative protocols that compartmentalised the sectoral components of development into separate verticals – economic, infrastructure, environmental, cultural, etc., – which made it difficult to introduce inter-departmental and inter-disciplinary practices to pursue reforms.

In the postcolonial context. the perpetuation of this colonial legacies are “mind-forged manacles”. They should have been challenged and broken after Independence, but instead they have been reinforced by globalization. However, as a vibrant democratic polity, there have been many civil society initiatives to find alternate strategies of conservation and development. In 1984, for instance, the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), was set up as a non-government organization (NGO) to stem the loss of the depth and diversity of the country’s cultural legacy and, in the last two decades, it has even spurred the government to introduce several innovative heritage-sensitive development programmes. But even these initiatives have seldom been critically evaluated.

For example, while the intents of these reform initiatives cannot be faulted, the fact is that from a critical perspective, they have not attempted to upend the existing paradigm but only mitigate or soften its harsher consequences and have ended up by reifying colonial legacies in a contemporary avatar. This is evident by critically examining the achievements of contemporary architecture, urban planning and the conservation practices, where ’modernist’ professionals continue to mimic western norms and models. The lesson to be drawn from this predicament is that one cannot break the Master’s house by using the Master’s tools.

It was in this light that the Indian Trust for Rural Heritage and Development (ITRHD) was established in 2011 as an NGO, with the express objective to formulate new ways to resolve old problems. As its appellation signals, it limited its focus to primarily engage with the preservation of the country’s rich rural heritage by developing its economic potential.

Though ITRHD is a small organization, it is currently working in 8 States (see www.itrhd.com) and both the Ministry of Culture and the XVth Finance Commission of the Government of India, have acknowledged its initiatives. By 2019, ITRHD realised that much of the work it had accomplished was routine and it needed to identify a potent theme that would draw attention to the significance of its vision to use heritage as a catalyst for development. After several brainstorming sessions, it was decided to focus on rural Buddhist heritage (PRBH).

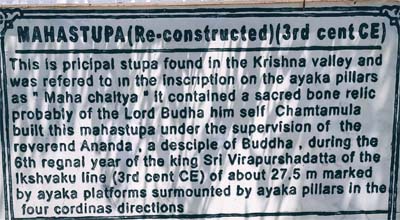

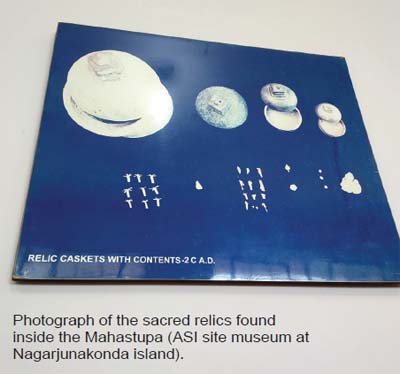

The subcontinent is the birthplace of Lord Buddha and it has many significant sites associated with his life and teachings, that are revered throughout the world, by Buddhist and lay people alike. Many of the iconic sites are already protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), but so deep and embedded was the influence of Lord Buddha and Buddhism in the subcontinent, that the country has profuse evidence of its historic sites that are in ruins or still unexplored, many in mofussil areas. These sites are being obliterated either on account of the ravages of time or the imperatives of modern development. Some are still venerated while others have a complex social and cultural relationship with local, national and international societies. ITRHD has proposed to convene an international conference to draw attention to not only protect the extant legacy, but also ensure that the process productively benefitted local societies.

In important objective of the conference is to set up a multi-disciplinary Academy for Rural Heritage Conservation and Development Training (Academy) to train, on the one hand, administrators, academics and professionals in various disciplines, and on the other, to also upgrade the capabilities of skilled workers, civil society interlocutors, including local residents. The Academy will focus on not only the challenges of conserving and managing the unprotected heritage, but also the many other critical social, cultural, environmental and economic issues that are increasingly being foregrounded in rural areas as the nation develops, transforms and modernises.

The objectives establishing the new Academy are to primarily explore how to link heritage and development as the preferred strategy to alleviate rural poverty and underdevelopment not only in India but also in South and Southeast Asia and thus promote mutually beneficial international dialogue on the subject. By focusing on the unprotected heritage sites, the Academy expects to bypass ‘universal’ protocols of protection and develop new strategies based on traditional knowledge systems and maintenance practices to conserve cultural heritage. This is timely because these new strategies will enable the pedagogy of the Academy to explore local ways to mitigate global problems created by climate change, disasters and conflicts.

Inter alia, the Academy expects to plug two important gaps in the existing education system. First, by focusing on strategies of rural development it will draw attention to the need to understand a neglected area of the transformation taking place in India, which is having a huge impact on the development of the country as a whole. And second, the routine curriculum and pedagogy of education in habitat related subjects are generally modelled on those developed in the West, which perpetuates colonial legacies. For instance, in the discipline of conserving historic buildings it obsessively focuses on preserving their materiality and aesthetics not the significance of its intangible attribute, thus failing to satisfy the cultural imagination of local societies. This will enable the Academy to develop new inter-disciplinary inputs from other fields like tourism, economics, cultural and anthropological studies to contribute to developing innovative rural development strategies.

There are no established models for such an Academy to guide ITRHD for setting up such a specialised institution. It takes into account that the adage that you cannot break the Master’s house by using the Master’s tools, to purposefully follow the principle of “learning by doing”. This strategy envisages that the curriculum and pedagogy of the Academy will evolve, step by step, and at each stage it will reassess its goals and strategies to address the needs of a transforming society. The learnings and recommendations from this international conference will be the first step in this journey.

ITRHD has already initiated dialogue with the Government of Andhra Pradesh to establish the Academy in their State. ITRHD has been offered a five-acre plot of land adjacent to the Nagarjunakonda archaeological site, to construct the Academy, which is in active consideration.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Prof. AGK Menon is Vice Chairman of INDIAN TRUST FOR RURAL HERITAGE AND DEVELOPMENT (ITRHD) organized the International Conference on Unprotected Buddhist Heritage and Sites. New Delhi on November 28th, 29th & 30th, 2025 at the Dr Ambedkar International Centre.

Prof. AGK Menon is Vice Chairman of INDIAN TRUST FOR RURAL HERITAGE AND DEVELOPMENT (ITRHD) organized the International Conference on Unprotected Buddhist Heritage and Sites. New Delhi on November 28th, 29th & 30th, 2025 at the Dr Ambedkar International Centre.