As China tightens control over the export of rare earth minerals, India’s automobile sector has raised alarm bells over supply shocks. As policymakers fire-fight the immediate disruption and seek to secure long-term supply, here’s a look at what rare earth minerals are, what caused the shortages and how the government is tapping possible workarounds to sustain growth in key sunrise sectors.

The US Connection!

It all started with Donald Trump’s tariff war! The POTUS imposed trade tariffs on China in April in a bid to arm-twist a trade deal, prompting China to retaliate by tightening the export of its much-sought-after rare earth minerals (REMs). The Chinese government mandated an end-user certification from importers and customers to ensure that such minerals were used only for non-military purposes. As the global leader, claiming two-thirds of global export value and 86 per cent of net supply in 2023, China’s retort to Trump’s gambit has the sunrise sectors, such as EVs and renewable energy (rare earth minerals are widely used in wind turbines and solar panels), on tenterhooks. China accounts for 40 per cent of all rare earth minerals deposits globally and 68 per cent of all rare earth processing. Naturally, therefore, its policy shift has profound global implications.

What Changed?

Thanks to the new Chinese rules, businesses importing REMs must provide a self-declaration and a client declaration, stating that they will not divert their exports for military purposes or re-export them to the USA. This new compliance requirement has increased the time to complete the procurement cycle to 45 days, disrupting industries and creating anxiety among manufacturers. The move triggered a crisis that continues to affect not only the automobile industry but several other key sectors globally. After all, rare earth minerals are widely used in electronics, defence, healthcare, aerospace and energy systems as well.

One of its casualties has been the Indian automobile industry, which has relied too heavily on Chinese rare earth minerals to power its expanding vehicle production capabilities, most notably EVs. This development has created anxiety among Indian vehicle manufacturers who fear a continued disruption could eat into their already slender margins. Several estimates suggest that increased duties and added supplier costs could spike the vehicle costs by 18-25 per cent, impacting sales and growth prospects.

One of its casualties has been the Indian automobile industry, which has relied too heavily on Chinese rare earth minerals to power its expanding vehicle production capabilities, most notably EVs. This development has created anxiety among Indian vehicle manufacturers who fear a continued disruption could eat into their already slender margins. Several estimates suggest that increased duties and added supplier costs could spike the vehicle costs by 18-25 per cent, impacting sales and growth prospects.

The leading industry voice, the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), has urged the government to ease import duties and local content requirements, besides providing a temporary reprieve in localisation norms under the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme and the PM E-Drive initiative. As reported by the Mint, in a letter to the Ministry of Heavy Industries, SIAM said: “In the current scenario, when there is a restriction on the import of standalone magnets, full assemblies, allied components, or sub-assemblies will have to be imported, which will attract a basic customs duty (BCD) of 15%, leading to an increase in the cost of vehicles.”

The clock is ticking as the festive season is around the corner. Months of October and November contribute as much as 30-35 per cent of the total annual vehicle sales. Delayed shipments, fast-depleting reserves of rare earth minerals and the fear of sustained supply chain disruption have created panic among key automobile players, prompting the government to step in. The government is reportedly undertaking stakeholder consultations to assess the possibility of subsidising the domestic production of rare earth magnets. But too much deliberation without concrete action could spell doom for the automobile industry that directly and indirectly employs 37 million people.

Can’t India Create Its Own Supplies?

Chinese suppliers are reportedly asking Indian vehicle manufacturers to import fully built motors instead of building them locally after sourcing rare earth magnets. This arrangement may offer temporary relief, but it could jeopardise the Indian government’s bid to manufacture locally in the long term. The government intends to boost local manufacturing capabilities and negate supply chain disruptions by reducing reliance on unreliable foreign sources. Supply chain disruptions across critical sectors since the pandemic, in the backdrop of a tepid bilateral ties with China, have forced the government to revisit its manufacturing and supply chain capabilities.

Chinese suppliers are reportedly asking Indian vehicle manufacturers to import fully built motors instead of building them locally after sourcing rare earth magnets. This arrangement may offer temporary relief, but it could jeopardise the Indian government’s bid to manufacture locally in the long term. The government intends to boost local manufacturing capabilities and negate supply chain disruptions by reducing reliance on unreliable foreign sources. Supply chain disruptions across critical sectors since the pandemic, in the backdrop of a tepid bilateral ties with China, have forced the government to revisit its manufacturing and supply chain capabilities.

Plus, ‘Make In India’ is a flagship initiative of the Modi government, and agreeing to source key components from a politically averse China is simply a no-go! Indian automakers plan EV sales to account for 30% of total vehicle sales by 2030 – another reason why diversifying supplies is crucial to ensuring that local capacities remain fully utilised.

India holds almost 7 million tonnes of rare earth elements, as compared to China’s 44 million tonnes. But China’s control of global supplies emanates more from its ability to mine and refine minerals – it has invested vast sums over many years to develop these capabilities. While India, too, could look downwards. However, such efforts are expensive and time-consuming. Mining and refining processes lead to air and water pollution and generate radioactive waste. In fact, the ores these rare earth minerals are extracted from usually contain radioactive chemicals, Thorium and Uranium. So, there are also ethical considerations! These challenges are forcing the government to find new partners, and PM Modi is already out to secure the supplies.

A Push From the Very Top to Diversify Supply!

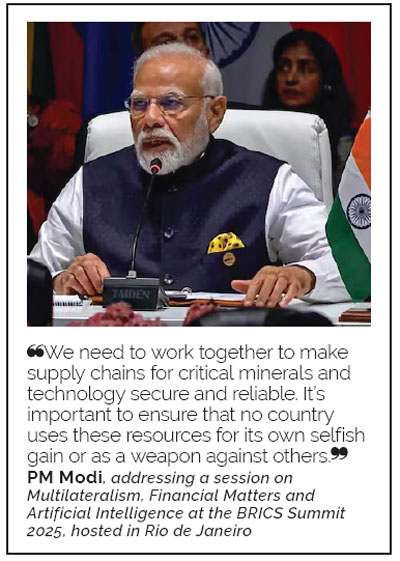

In one of the rare instances when the PM has been out of the country for more than a week, PM Modi undertook a 5-nation tour recently, including participating in the BRICS Summit. One of the key agendas of his visit was to secure the supply of rare earth minerals. In his bilateral meetings with leaders of Ghana, Namibia, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina and Brazil, he stressed the need to boost ties in areas such as critical minerals. Namibia, in particular, has vast reserves of lithium, cobalt and uranium.

In one of the rare instances when the PM has been out of the country for more than a week, PM Modi undertook a 5-nation tour recently, including participating in the BRICS Summit. One of the key agendas of his visit was to secure the supply of rare earth minerals. In his bilateral meetings with leaders of Ghana, Namibia, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina and Brazil, he stressed the need to boost ties in areas such as critical minerals. Namibia, in particular, has vast reserves of lithium, cobalt and uranium.

Brazil has three times more reserves of rare earth minerals than India, with the second-largest reserves globally. Incidentally, the South American nation has recently made significant efforts to ramp up its production capabilities to fill the vacuum created by China and to emerge as the leader in critical minerals. Serra Verde mining company, an American company controlled by Denham Capital, commenced commercial production from its Pela Ema rare earths deposit in Goiás state in 2024. Publicly available information suggests that the company expects to produce 5,000 metric tonnes of rare earth oxide annually by 2026, which would position Brazil as a global leader in rare earth minerals and benefit India as both nations enjoy excellent ties.

Outro

Rare earth minerals are not all that rare at all! In fact, they are found in the Earth’s crust in abundance. The complex process of mining, extracting and refining them for commercial usage makes them extremely rare in the marketplace, giving them their misleading name. In terms of the available reserves, China leads the pack, followed by Vietnam, Brazil, Russia and India. The pecking order changes in terms of the production numbers. China yet again leads the pack, followed by the USA, Myanmar, Australia, Thailand and Nigeria.

17 rare earth elements or minerals, broadly classified into 15 lanthanides, and Scandium and Yttrium are mostly dispersed in the Earth’s crust, mixed up with other minerals. Thanks to this complication, processing them for commercial use takes complex separation and refining capabilities. That the process causes substantial air and water pollution, and generates radioactive waste, makes it all the more complicated for most countries to pursue such ambitions. Managing such challenges while developing mining and refining capabilities requires large investments and significant time.

17 rare earth elements or minerals, broadly classified into 15 lanthanides, and Scandium and Yttrium are mostly dispersed in the Earth’s crust, mixed up with other minerals. Thanks to this complication, processing them for commercial use takes complex separation and refining capabilities. That the process causes substantial air and water pollution, and generates radioactive waste, makes it all the more complicated for most countries to pursue such ambitions. Managing such challenges while developing mining and refining capabilities requires large investments and significant time.

These minerals are used across sectors like defence, renewable energy and high-technology industries. In defence, rare earth minerals are used for precision-guided munitions, fighter jets and radar systems.

In the electronics sector, Yttrium and Terbium are used to make phosphors in LED and computer screens. Permanent magnets used in microphones and hard disks are made with Neodymium and Praseodymium. Meanwhile, elements like Cerium oxide and Lanthanum oxide are used in catalytic converters to reduce emissions in internal combustion engines and in petroleum refining.