History and Mandate

As the High-Level Segment of the UN General Assembly is in session and as we wait to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the establishment of the Organization on 24 October 2025, it is timely and useful to reflect on two propositions: first, that the United Nations (UN) is perhaps facing its most challenging crisis since its founding in 1945 because of the undermining of both its Charter and functioning by some of the UN’s most powerful founding Member States and some other Member States supported by the former; second, that notwithstanding these challenges and its imperfections, the UN still remains the world’s greatest and most enduring hope for the provision of global peace and security, human rights and global public goods.

The UN is also still the closest to the type of premier global governance multilateral mechanism the world desperately needs at a time of both accelerating, now Artificial Intelligence (AI) driven globalization and multiple intersecting crises that range from illegal military interventions, genocide and systemic human rights abuses, a potential global tariff war and impending global recession. There is no doubt that the UN needs to be reformed—even transformed—but it also simultaneously needs to be strengthened and properly resourced if it is to address the formidable peace and security, human rights, humanitarian, global public goods, sustainable development and other transnational challenges of the 21st century.

The 2024 UN Pact for the Future and its two related documents, the Global Digital Compact and the Declaration on Future Generations agreed at the UN Summit for the Future in New York by consensus in September last year, are testimony to the fact that the UN will remain at center stage in terms of the world’s current and future global, regional and national governance architecture. The UN Charter’s principles and values are timeless and as relevant today as they were in 1945. While some important amendments to the Charter are unsurprisingly necessary to account for the considerable changes which have taken place from the time it was written and agreed 80 years ago, any attempt to start an entirely new process of creating a new Charter or building a new international Organization to replace the current United Nations would be a mistake and result in mayhem.

That said, High-Leveledented geopolitical and geoeconomic events, especially since Trump 2.0 began on 20 January 2025, and his administration’s undermining of global multilateralism of which the UN is both the anchor and bedrock, require yet another urgent reaffirmation of both the Charter and the Organization this week during the High Level Segment of the 80th UN General Assembly (UNGA) currently underway in New York City. This is necessary because as the current UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres warned the UNGA on 26 June this year, UN Charter Day, the foundational UN document and its principles, written as a ‘….declaration of hope’ are suffering ‘…assaults….like never before,’ with countries following ‘… an all too familiar pattern: follow when the Charter suits, and ignore when it does not’. Guterres added that the Charter ‘…is not optional, and it is not a la carte menu…. We cannot and must not normalize violations of its most basic principles’.

That said, High-Leveledented geopolitical and geoeconomic events, especially since Trump 2.0 began on 20 January 2025, and his administration’s undermining of global multilateralism of which the UN is both the anchor and bedrock, require yet another urgent reaffirmation of both the Charter and the Organization this week during the High Level Segment of the 80th UN General Assembly (UNGA) currently underway in New York City. This is necessary because as the current UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres warned the UNGA on 26 June this year, UN Charter Day, the foundational UN document and its principles, written as a ‘….declaration of hope’ are suffering ‘…assaults….like never before,’ with countries following ‘… an all too familiar pattern: follow when the Charter suits, and ignore when it does not’. Guterres added that the Charter ‘…is not optional, and it is not a la carte menu…. We cannot and must not normalize violations of its most basic principles’.

This needs to be unequivocally accepted by all 193 UN Member States and publicly reaffirmed at the forthcoming September 2025 gathering of Heads of State, Foreign Ministers and senior officials currently underway in New York. It must also be agreed there that if the UN did not exist, it would have to be reinvented and a new Charter and Organization, if created in the illiberal world we live in today, would be far worse than the inspiring UN Charter and Organization which were agreed, created and unanimously endorsed eight decades ago.

Main Achievements

Any objective assessment would conclude that the UN’s three main pillars—peace and security, human rights, and development—have stood the test of time. These three pillars are integrally linked: you cannot have peace and security without development or development without peace and security, and neither will be possible without human rights. Many of the world’s current seemingly intractable problems exist because of a lack of appreciation by both policy makers and ordinary citizens about the importance and interconnectedness of these three pillars.

Any independent evaluation of the Organization will also probably conclude that it has made an enormous, largely measurable, positive and constructive contribution to the world and its citizens over the last 80 years. The list of UN accomplishments is long and impressive and cannot be elaborated in this short article. Only a few ‘big picture’ ones can be enumerated here. At the top of the success list is overseeing decolonization which is, indeed, one of this world body’s early historic achievements. Its other major achievements include, but are not limited to: significant contributions towards preventing a third world war so far; the adoption of universal human rights normative standards and institutions around much of the world; saving millions of lives during humanitarian crises; eradicating life-threatening diseases; significantly facilitating the fastest pace of genuine global, regional and national developmental progress in world history; and achieving an unprecedented global consensus in 2015 by all its 193 Member States on the human rights based Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Agenda 2030, by far the most ambitious global development agenda ever agreed in world history.

In terms of its continuing contributions at a more practical level and on a day-to-day basis, the world and its people should not forget what the women and men of the United Nations do every day. In 2024, they were daily protecting and assisting 123.2 million refugees and other forcibly displaced people who had to flee their homes. As a result of both the World Health Organization’s (WHO) own and its supported groundbreaking research work on vaccines as well as WHOs and the United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEFs) supported global delivery on the ground, 89 per cent of all infants globally had at least one dose of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DPT) by 2024 while 85 per cent had all three; the UN World Food Programme (WFP) provided food assistance to 153 million people in over 120 different countries in 2023; while 76,671 men and women in uniform were providing UN peacekeeping duties in May 2023. These are just a few examples.

Unprecedented Global Challenges

Despite the UNs innumerable, undeniable ‘big picture’ and more down-to-earth past and continuing achievements and successes, the 21st century we now live in is confronted with many challenges, both new and old.

A major concern for the peace and security pillar is the increase in the number and intensity of large-scale crises. Transnational violent extremism has also emerged as a universal preoccupation and concern over the last few decades. In addition, climate related natural disasters are becoming more existential and frequent (with 45.8 million disaster related forced displacements as of 2024), and their destructive impacts are more intense. Every year, the world continues to achieve the wrong set of records, whether on pollution, rising sea levels, or greenhouse gas concentrations.

In terms of the development pillar, addressing climate change remains the world’s most urgent and existential crisis, but growing transnational and national inequalities and the effective governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the public interest for the global public good are equally important. An additional related major set of challenges are the multiple crises of governance fueling disruption and violence. COVID-19 served to compound the world’s challenges and make matters even more dire, also heightening the risk of future pandemics, which no single country, however powerful, can guard itself against as Covid-19 vividly demonstrated.

The world cannot even begin to hope that these multiple and often interlinked crises will be adequately addressed or overcome without a reaffirmed, albeit renewed, transformed and revitalized United Nations for the 21st century.

Trump 2.0 and its Multiplier Effects: An Existential Threat to the Post World War Two Global Liberal Order

The lead and most important founding Member State of the United Nations in 1945, the United States of America (US), has become its most significant threat from within under Trump 2.0. symbolized most recently by his most irresponsible (e.g. climate change, immigration) and unstatesmanlike speech during the High-Level Segment of the UN General Assembly on September 23. Indeed, his second Presidency has the real potential to obliterate many of the tangible peace and security, human rights and development gains resulting from eight decades of global liberal idealism embodied and led by the United Nations. Even George W Bush’s unilateral invasion of Iraq in 2003 under false pretenses, willfully violating both the international rule of law and the UN Charter, did not fundamentally question or irretrievably undermine the existing UN based global liberal world order as Trump’s actions are doing today.

The current financial delinquency of the US to the UN is being made worse, sadly and somewhat surprisingly, by another UN Security Council (UNSC) Permanent 5 (P5) member, the UK, (shockingly under a Labour government) and some middle European powers (e.g. Sweden, Netherlands) who are amongst the biggest beneficiaries of a UN embedded global multilateral system. This comes at a time when they and the UN need each other like never before since the Organization’s founding.

The UK and many European Union (EU) members, preoccupied with their own existential domestic immigration, defense, economic, financial and foreign policy crises, partly created by Trump 2.0 but partly by their own policies, appear to be cutting their aid to both the UN and the poorest countries, viewing such cuts as a soft target, given NATO Members’ June 2025 agreement to increase their annual defense requirements and defense and security related expenditure to of GDP by 2035 and because, for political reasons, they cannot easily cut social welfare programs at home to finance their defense needs.

EU members, such as Sweden, who have been amongst the UNs staunchest and most consistent defenders since its founding 80 years, like the US, under its current right wing government, permanently stopped its core contribution to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in 2024, during the Israeli genocide of Gazans, at the worst possible time. This was unthinkable of Sweden till very recently.

The UK, Sweden and the Netherlands should urgently reverse course. Collectively, together with France, Germany, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Mexico, Japan, the Republic of Korea and key countries in the Global South (e.g. BRICS members such as Brazil, India and South Africa, Turkiye, ASEAN members), they should be prioritizing filling the fast-growing liquidity and financial gap left by the US in support of an appropriately adapted and reformed UN. They need to put their money where their mouth is when they plead allegiance to the UN Charter above all else as the European Union (EU) just did together with Mexico, Brazil and India, in the corridors of the UN in New York this week.

The UK, Sweden and the Netherlands should urgently reverse course. Collectively, together with France, Germany, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Mexico, Japan, the Republic of Korea and key countries in the Global South (e.g. BRICS members such as Brazil, India and South Africa, Turkiye, ASEAN members), they should be prioritizing filling the fast-growing liquidity and financial gap left by the US in support of an appropriately adapted and reformed UN. They need to put their money where their mouth is when they plead allegiance to the UN Charter above all else as the European Union (EU) just did together with Mexico, Brazil and India, in the corridors of the UN in New York this week.

The current illiberal conjuncture and financial gap in core funding to the UN leaves a vacuum which an even more illiberal China can and may well fill across the UN and the multilateral system if the countries mentioned above do not come together and deliver and prove that they are up to the challenge of protecting the liberal, democratic, global world order underpinned by the UN.

China’s contribution to the UNs core budget now amounts to around $680 million (roughly of the UNs core budget) as against the US which has an assessed contribution of $820 million (roughly ). Both powers also make large voluntary contributions to UN activities and programs through its specialized agencies, which China is increasing while the US is cutting. Against this, India’s contribution to the UNs core assessed budget is only a paltry $ 38 million, approximately of the UN core budget’s total, despite its claim to soon become the third largest economy in the world after the US and China.

Unlike the US, China has, so far, been a more responsible UN member state in many ways since it remains committed to paying its core “assessed” contributions, even if its payments are often very late. The US remains delinquent on them in 2025.

Turning Crisis into Transformative Opportunity to Achieve Peace and Security, Human Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals

The UNs sustainable development pillar is increasingly threatened particularly because progress on the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Agenda 2030 is way off track and the US under Trump has disavowed the goals as an infringement on its national sovereignty and Make America Great Again (MAGA) aspiration, despite having endorsed and signed them under President Obama in 2015. Achieving this human rights-based Agenda is vital not just for sustainable development but for maintaining both peace and security and promoting and protecting human rights.

The most important reform initiatives needed for a transformed, “fit-for-purpose” UN for the 21st century are outlined below:

1. Fully implement the agreed 2019 One UN Development System (UNDS) Reform Agenda intended to move towards a One UN and expand it in an integrated and coherent manner to encompass all levels: global, regional and country building on the “Delivering as One” pilot phase of two decades back.

At the global level, this will require merging overlapping institutional mandates, agencies, boards, policies, committees and reducing and merging staff.

At the regional level, there must be an urgent, thorough, objective review of the work of all the UN Regional Economic Commissions (RECs) to enhance and sharpen their value added on the provision of regional public goods and make it more strategic.

Country level action is most important for the achievement of the SDGs. At country level, Vietnam, perhaps, has provided a best practice example of the One UN in practice over the last two decades with demonstrable results in terms of achieving all the 2015 Millenium Development Goals (MDG) early as well as progress on the SDGs.

A key lesson from Vietnam’s experience is the importance of the government leading the One UN on the ground. Without this leadership, progress on achieving the SDGs will be slower than what it would otherwise have been. This remains a challenge in many developing countries.

2. Redefining the Development Pillar to Prioritize Global Public Goods

The UN should declare justified success in terms of its support for traditional development areas such as poverty reduction, basic health and education over the last 80 years since the vast majority of its decolonized member states, with Vietnam again being a prime example, are now able to finish the last mile work in these areas using their national budgets and without UN financial support (a few least developed countries (LDCs) and landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) may require some continuing support in these areas but they are a small minority).

The UN should declare justified success in terms of its support for traditional development areas such as poverty reduction, basic health and education over the last 80 years since the vast majority of its decolonized member states, with Vietnam again being a prime example, are now able to finish the last mile work in these areas using their national budgets and without UN financial support (a few least developed countries (LDCs) and landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) may require some continuing support in these areas but they are a small minority).

Instead, the UNs development pillar should now prioritize global public goods such as climate change, energy security and AI governance as top priorities as well as inequality reduction and good governance.

3. Reinvigorating and Integrating the Peace and Security Architecture

Three illegal invasions in recent years show that the UNs peace and security and nuclear non-proliferation architecture have stopped functioning as they should: it was both undermined and bypassed in Ukraine by Russia and in Gaza, Lebanon, Iran and now even Syria by Israel with US support. The UN Charter and the international rule of law have been abused not only by UN Security Council Permanent 5 (P5) members such as the US (Iraq, Afghanistan, now Iran) and Russia (Crimea in 2014 and all of Ukraine since 2022) but by smaller countries (Israel) armed and effectively backed by bigger powers (USA, Germany, UK).

Making the UN effective in maintaining peace and security again, the main reason for its creation after World War II, will require both the integration of and greater coherence between all of the different parts of this architecture as well as strengthening the UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) to enable it to take up some of the UNSCs agenda, leaving the latter to concentrate on the most important “big picture” transnational peace and security issues.

Making the UN effective in maintaining peace and security again, the main reason for its creation after World War II, will require both the integration of and greater coherence between all of the different parts of this architecture as well as strengthening the UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) to enable it to take up some of the UNSCs agenda, leaving the latter to concentrate on the most important “big picture” transnational peace and security issues.

In addition, addressing the following long-standing challenges and agreeing and carrying out enforceable reforms to address them should be an urgent, top priority.

Broadening UNSC Permanent Member Composition

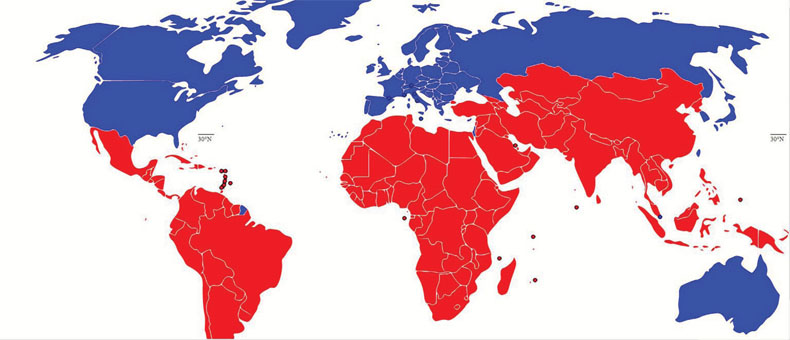

The UN has lost some of its political legitimacy over the last three decades, relative to what it enjoyed in its first five decades. This is a result of structural design flaws that have existed from its inception in 1945 which became increasingly visible and problematic after the simultaneous fall of the Berlin Wall and Soviet Union and rise of some of the larger emerging economies in the Global South in the original BRICS grouping, namely India, Brazil and South Africa.

It is now universally agreed that the P5 members of the UNSC (USA, China, Russian Federation, United Kingdom, France) do not and cannot represent the changed geo-political, geo-economic, demographic or even realpolitik realities in a dramatically changed 21st century world. The P5, visibly and untenably, excludes the Global South which now comprises a significant percentage of the world’s population and economic wealth. It also excludes Germany and Japan.

In the P5 Security Council context, the United Kingdom, France and even Russia are now anomalies, given their significantly reduced 21st century geo-economic and geopolitical weight. They should have been obliged to exit permanent membership long ago, ideally in 1991, when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) dissolved. This was a golden missed opportunity both to reform and transform the UN Security Council. Such an opportunity is unlikely to present itself in the foreseeable future.

The dire need for a more democratically constituted and 21st century relevant UN Security Council, nevertheless, remains urgent and essential. Most UN Member States support a comprehensive reform of the Council which means an expansion in both the permanent and non-permanent categories, not a piecemeal reform.

While India, Brazil and even South Africa’s demands for such inclusion are legitimate in terms of Global South representation, the bar for Permanent Membership of the UNSC should be higher than it was in 1945 at the UNs founding if we want a better future world than what we inhabit today. Each one of the new aspirants needs to demonstrate more consistently and clearly than the current P5 that they can put global and regional interests before their narrowly defined national interest.

UNSC Paralysis and Crisis

The paralysis and crisis of and in the UNSC has been repeatedly and continuously visible from the turn of the century. This was evident in both its inappropriate and inadequate responses, or lack thereof, to the Iraq, Syrian and Libyan interventions by major powers starting more than two decades ago as well as by its inability to do anything of significance to stop the current illegal interventions in Ukraine, Gaza and Iran. It has also not done enough on the world’s existential climate and other major social and economic security challenges.

The P3 (the US, China and Russia), within the P5 of the Council, have also repeatedly undermined both its credibility and effectiveness and that of the UN, through attempts to entirely bypass the Council (e.g. the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the recent 2025 unilateral attack by Israel and the US on Iran) or through the exercise of their veto power in an inappropriate and narrowly self-interested manner (e.g. repeated unconscionable US vetoes in favor of Israel, Russian and Chinese vetoes on Syria to protect the Assad regime as well as the Russian blockage of UNSC discussions and resolutions on its illegal invasion in Ukraine since 2022).

The P5 must recognize, in their own self-interest, even if not because this is clearly in the global interest, that they risk throwing the “baby out with the bath water”, if they do not both broaden permanent Security Council membership and restrict the use of the P5 veto.

Exercise of the P5 Veto Power in the UN Security Council

While there is a strong case to abolish the UN Security Council P5 veto power because of this glaringly narrow partisan record, as well as to prevent further abuse and misuse, this is unrealistic and unlikely in the short term because current permanent member states (the P5) will not give up the veto very easily or quickly. The UN Security Council P5 veto power, agreed in 1945 as a prerequisite to UN Charter adoption, was built into the system as an insurance that the system itself would work and that the major powers would not act outside it. Despite the glaring exceptions mentioned above and the overwhelming use of it to protect one country, Israel, in particular, that probably largely remains true in overall terms even today.

A strong case can certainly be made for restraint on the use of the veto (e.g. its use only for matters which are central for the absolute national security of a UN Member State). This may also be both more realistic and desirable.

There have already been a few noteworthy initiatives in the UN General Assembly (UNGA) to restrict the use of the veto and strengthen the accountability of the Security Council to the UNGA. This was already foreseen and envisaged when the UN Charter was drawn up in 1945, so it does not require any change to the UN Charter.

The most noteworthy of these is Liechtenstein’s 2020 “Veto Initiative,” spurred by deadlock at the UNSC on the Syrian war. While the resolution was delayed because of Covid-19, it was adopted in the UNGA by consensus on April 26, 2022. This was quite a remarkable achievement, led by one of the UNs smallest member states. It was also unprecedented since it “creates a standing mandate for the UNGA to be convened automatically, within ten working days, every time a veto has been cast in the Security Council.”

This Initiative needs to be urgently reinforced, mainstreamed and built upon. It is significant that three P5 members, the UK, France and the United States (during the Biden Administration) supported the Liechtenstein initiative while France together with Mexico, had initiated a declaration seeking restrictions on the use of the UNSC veto as far back as 2015.

Together with the “Uniting for Peace” mechanism, which allows the UNGA to step into and fill serious security gaps left by the Security Council, this should lead to greater accountability of the Council to the UNGA which is a more democratic body with universal membership, one-country, one-vote and no veto power. The 1950 Uniting for Peace resolution has also been increasingly invoked recently, both in the case of Ukraine and Gaza, including in a UNGA resolution and vote leading to Russia’s expulsion from the UN Human Rights Council.

Much more can be done in the General Assembly, nevertheless, but unfortunately, there is a limitation. Any radical reform of its role, for example, giving it the power to pass binding resolutions on matters relating to peace and security, would necessarily require an amendment of the UN Charter. Such an amendment requires the buy-in of the entire current P5 in the Security Council, which is not something which will happen very easily.

The proposal of India and many other countries in the Global South to convene a UN Charter Review Conference, as a first step towards fundamental UNSC Reform, should continue to be pursued. The 80th Anniversary of the founding of the Organization in October 2025 is the perfect opportunity to launch such a Charter Review Conference.

4. Enforcing Human Rights Conventions and Resolutions and Making their Coverage more Comprehensive

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was as pathbreaking and inspiring as the UN Charter. The main challenge remains enforcement of UN Conventions and resolutions in this area, including but not limited to the UNs Genocide Convention against Israel at the current time. Greater comprehensiveness and coherence of what the human rights architecture covers is also needed, especially in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals and the current multiple peace and security and human rights crises.

5. The Continuing and Accelerating Resources Crunch

The UN is arguably the world’s most underfunded multilateral organization given its formidable breadth and depth of global governance and other mandates. The Organization continues to be forced to attempt to address them despite the visible absence of adequate demonstrated political will or even open obstruction by many of its most powerful Member States. This political will deficit has translated into both inadequate core “assessed contributions” which are now strikingly incommensurate to the UNs long and growing list of mandates and responsibilities. This had become a cumulative and growing problem for the UN even before the arrival of Trump 2.0, with negative consequences for the fulfilment of even some of its core mandates such as the 2019 UN Development System Reform and Peacekeeping. As a result of cuts (UK), late payments oftentimes of even what was agreed (China) or, under Trump 2.0, an unprecedented unwillingness by the US to pay its arrears and 2025 assessed contribution, this has now created both an existential liquidity and budget crisis for the UN Secretariat.

To understand both the magnitude and nature of the UNs current liquidity and financial crisis, it should be noted that of the total annual budget for the entire UN family of USD 74.3 billion in 2022, were ear-marked funds. This reflects a retreat from the true spirit of multilateralism. The Organization needs to get core resources which can be used for what the UNs Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks prioritize, not what donors earmark their funds for.

To understand both the magnitude and nature of the UNs current liquidity and financial crisis, it should be noted that of the total annual budget for the entire UN family of USD 74.3 billion in 2022, were ear-marked funds. This reflects a retreat from the true spirit of multilateralism. The Organization needs to get core resources which can be used for what the UNs Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks prioritize, not what donors earmark their funds for.

The already prevailing liquidity and resources crunch at many UN agencies has escalated in the six months of Trump 2.0, forcing the WHO, for example, to freeze all hiring across the world to the detriment and even death, in some instances, of some members of poor, already disempowered and marginalized population groups in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) is in crisis given that it has relied on the US for around of its resources which have now been entirely cut since Trump 2.0 began, with little notice. It now faces a probable sunset clause in 2026.

The UNs transformative reforms outlined in this article remain essential. There are also longstanding, bureaucratic inefficiencies and wastage which need addressing through internal organizational reforms, some of which are currently ongoing. However, neither of these should become an excuse for UN Member States to delay addressing the “bigger picture” liquidity and resources crunch which the UN currently faces, which is preventing the fulfilment of many of its mandates which no other Organization can ever hope to replace or fulfil.

(This article is a shorter version of a full length article by Kamal Malhotra which will be published in the India International Center Journal, Autumn Issue in October 2025, on the occasion of the 80th Anniversary of the United Nations).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kamal Malhotra is currently Distinguished Visiting Professor at the NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad, India. He was a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center between June 2022-May 2025. He has also Guest Lectured at the School of Interwoven Arts and Sciences (SIAS), Krea University, India. Prior to his retirement from the United Nations in September 2021, Mr. Malhotra had a rich career of over four decades as a management consultant, in senior positions in international NGOs, as co-founder of a think-tank, FOCUS on the Global South, and in the United Nations (UN) including as its Head in Malaysia, Turkiye and Vietnam (2008-21). He was UNDPs Senior Adviser on Inclusive Globalization, based in New York, USA, for most of the prior decade. Mr. Malhotra is widely published.

Kamal Malhotra is currently Distinguished Visiting Professor at the NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad, India. He was a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center between June 2022-May 2025. He has also Guest Lectured at the School of Interwoven Arts and Sciences (SIAS), Krea University, India. Prior to his retirement from the United Nations in September 2021, Mr. Malhotra had a rich career of over four decades as a management consultant, in senior positions in international NGOs, as co-founder of a think-tank, FOCUS on the Global South, and in the United Nations (UN) including as its Head in Malaysia, Turkiye and Vietnam (2008-21). He was UNDPs Senior Adviser on Inclusive Globalization, based in New York, USA, for most of the prior decade. Mr. Malhotra is widely published.