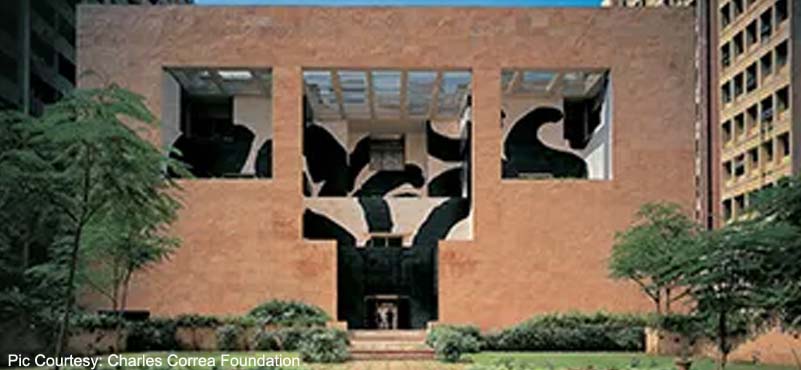

The closure of the British Council Library (BCL) in Chennai on February 15, 2026, is deeply saddening. With this decision, the presence of the British Council’s physical libraries in India will be reduced to just two centres—Kolkata and Delhi. This narrowing footprint marks not merely the closure of a building, but the gradual fading of an institution that once played a vital role in India’s intellectual and cultural life.

Closure of British Libraries- Not a one-off event but part of a clear pattern

The shutting down of BCL libraries across multiple cities is particularly painful because these libraries were once iconic spaces of learning, dialogue, and quiet discovery. However, this process has been unfolding over a long period. The British Council Libraries in Lucknow and Patna were closed nearly three decades ago, in the mid-1990s. Subsequently, libraries in other cities like Bengaluru, Ahmedabad, Chandigarh, Hyderabad and Pune, BCL also closed physical libraries in 2020 and went fully digital, responding to the technological inflexion and possibly as a part of the larger austerity drive. The disappearance of such centers, one after another, often quietly and without much public debate causes concern and consternation among students and teachers in general and the well-informed reading public in particular.

What we are witnessing now is the near-complete withdrawal of a once-flourishing network of public knowledge spaces.

For many Indians of an earlier generation, the British Council Library was far more than a repository of books. It was a window to the wider world.

The Lucknow Center- Personal reflection

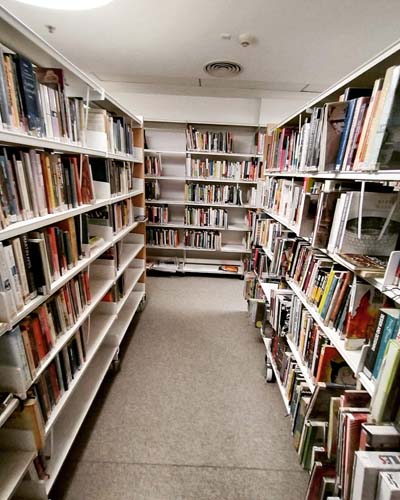

I was a member of the British Council Library in Lucknow for three or four years in the late 1970s or early 1980s. The annual membership fee—possibly around Rs. 100—was considered substantial at the time, yet it felt entirely justified. The reason lay in the extraordinary quality and range of its collection.

The library offered access to books that were otherwise difficult to find: fiction and serious literature, philosophy and economics, science and social sciences, along with an impressive array of journals, magazines, and newspapers from across the world. One could borrow up to four books and two magazines at a time—books for a month and magazines for two weeks—an arrangement that encouraged deep, unhurried reading.

Equally memorable was the physical space itself. The library provided a calm, dignified, and intellectually stimulating atmosphere. Complete air-conditioning made it a welcome refuge from both the oppressive summers and the biting winters of Lucknow. Its location added to its charm—it was housed on the first floor of the Mayfair Building in Hazratganj, the cultural and commercial heart of the city. Visiting the library often felt like a small but meaningful ritual, combining learning with a sense of belonging to a wider community of readers.

Beyond books, the British Council Library symbolised openness, curiosity, and the exchange of ideas across cultures. It introduced generations of students, researchers, teachers, and general readers to global scholarship and contemporary debates long before the internet made such access commonplace. In many ways, these libraries helped shape intellectual confidence, critical thinking, and cosmopolitan outlooks among their members.

Cut to the Present

This depressing situation is deeply worrying in the present context, where the habit of sustained reading has alarmingly declined. A 2024 study in the United States indicates that average daily screen time has climbed to nearly 7.5 hours, while time spent reading books, newspapers, and long-form print has shrunk to just 25 minutes. The contrast is stark, terrifyingly so! While digital platforms offer immediacy, interactivity, and constant updates, they rarely cultivate the depth, patience, and reflection that reading demands. Print may not be as fast-paced or visually stimulating as the internet, but it advances information, insight, and knowledge in ways that fragmented online browsing simply cannot replicate.

Reading Matters- It certainly does!

This argument is powerfully developed in the book Reading Matters by Joel Halldorf, professor at University College Stockholm. In this thought-provoking book, Halldorf highlights the many intellectual, cultural, and even moral advantages of reading, while warning of the serious consequences—if not the peril—of abandoning it. He persuasively argues that reading is not merely a hobby or leisure activity; it is a civilizational achievement that shapes how we think, reason, and relate to the world.

Consider the long arc of human history. It took approximately 65,000 years for humanity to move from spoken language to written language. Writing—and therefore reading—is only about 5,000 years old. Unlike speech, it is not a “natural” human gift that emerges automatically. Reading is an acquired skill that requires sustained effort, discipline, and practice. When neglected, it weakens. Just as unused muscles atrophy, so too does the capacity for deep reading if it is not exercised regularly.

The transformative power of reading is evident throughout history. The approval of the first English Bible in 1539 made scripture accessible beyond clergy and elites, reshaping religious life in England. Likewise, Martin Luther’s printed pamphlets were instrumental in igniting the Reformation, demonstrating how the written word can disrupt established systems and mobilize masses. Later, ideas about liberty, democracy, the abolition of slavery, human rights, and scientific progress spread through books and pamphlets. Print culture empowered individuals to engage with complex arguments and to question authority.

Reading did not merely spread ideas; it transformed thought itself. As Halldorf observes, oral societies tend to rely on memory, storytelling, and formulaic expression. While rich in tradition, they are less suited to constructing and preserving highly complex, layered arguments. Writing, by contrast, allows for clauses, sub-clauses, footnotes, and extended reasoning. It enables careful analysis, systematic logic, and the accumulation of knowledge across generations. By the nineteenth century, Western societies had become deeply bookish. Reading was a widespread habit; people carried books, annotated margins, and engaged in long debates through letters and essays.

However, the twentieth century began to erode this dominance of print. Cinema introduced visual storytelling on a mass scale. Radio revived oral communication. Television added moving images to the mix. And now, smartphones with their endless notifications, short videos, scrolling feeds, and algorithm-driven content have accelerated this seemingly inexorable shift. We appear to be circling back toward a predominantly oral and visual culture, albeit in digital form.

Actions have consequences

Halldorf warns that this shift carries consequences. As attention spans shorten and reading becomes fragmented into headlines, captions, and posts, our ability for deep reasoning may erode. Complex arguments are replaced by sound bites. Nuanced debate gives way to outrage and reaction. The phenomenon sometimes mockingly called “WhatsApp university”—where misinformation spreads rapidly through forwarded messages—illustrates how easily shallow, unchecked claims can thrive in a culture that does not habitually read critically. Social media thuggery, fake news, and viral half-truths flourish in environments where people skim rather than study.

Moreover, reading fosters qualities that digital consumption often undermines: patience, empathy, concentration, and imagination. Immersing oneself in a book requires sustained attention and mental effort. It invites readers to inhabit perspectives different from their own, strengthening empathy and moral reflection. It trains the mind to follow arguments carefully and to weigh evidence before forming conclusions. These habits are essential not only for personal growth but also for democratic citizenship.

The decline of reading, therefore, is not a trivial lifestyle shift. It represents a deeper cultural transformation. If societies lose the habit of deep reading, they risk losing the capacity for critical thought, informed judgment, and intellectual independence. Reclaiming time for books may seem old-fashioned in a hyper-connected age, but it may well be one of the most radical and necessary acts for preserving thoughtful, reasoned public life.

The decline of such institutions raises uncomfortable questions about the challenge of change, and the need for serious study, introspection and debate.

In an age of digital abundance – an age where we are often swamped by digital overkill- we often underestimate the value of physical libraries as public spaces—places that nurture concentration, serendipity, and human connection. Not everyone has equal access to digital resources, nor can online platforms replicate the quiet discipline and democratic accessibility of a well-run public library.

The Significance of Libraries

I have repeatedly argued in my Speeches and writings for the last thirty years that Libraries cannot—indeed, must never—be judged solely by the narrow calculus of cost-benefit analysis, circulation statistics, or membership counts. Their value lies beyond quantifiable outputs. A library is not merely a service provider; it is a civilizational institution. It safeguards memory, nurtures dissenting thought, and offers the intellectual soil from which transformative ideas emerge. Its significance often reveals itself not in immediate returns, but in the long arc of history.

Consider the example of Karl Marx. After settling in London in 1849, he spent more than three decades immersed in research at the Reading Room of the British Museum. That space functioned as his intellectual laboratory—his “office.” There, he examined economic data, parliamentary reports known as Blue Books, historical accounts, and political writings. The result of this sustained engagement was Das Kapital, a work that profoundly shaped political movements, economic debates, and social theory across continents. No cost-benefit ledger at the time could have predicted the global consequences of one scholar quietly reading under a domed ceiling.

Yet Marx is only one illustration. Libraries have repeatedly served as incubators of paradigm-shifting ideas. They provide:

1. Long-term Intellectual Incubation

Great works often require years—sometimes decades—of uninterrupted study. Libraries offer stability, continuity, and access to accumulated human knowledge. Scholars, scientists, and writers rely on this sustained environment to test hypotheses, compare sources, and refine arguments.

2. Equal Access to Knowledge

Libraries democratize learning. They reduce the barriers of wealth, geography, and status. A student from a modest background can access the same classical texts, scientific journals, or philosophical treatises as a university professor. This leveling function fuels social mobility and intellectual diversity.

3. Preservation of Cultural Memory

Manuscripts, archives, rare books, and historical records preserved in libraries protect societies from collective amnesia. Future discoveries often depend on past documents. Breakthroughs in medicine, law, and history frequently emerge from revisiting archived materials with new perspectives.

4. Safe Spaces for Intellectual Freedom

Libraries defend the freedom to read and think independently. They house competing ideologies side by side, enabling readers to evaluate, critique, and synthesize ideas without coercion. This pluralism is essential for scientific advancement and healthy democratic discourse.

5. Interdisciplinary Cross-Pollination

Innovation often arises at the intersection of disciplines. In a single building or increasingly through digital collections, an engineer might encounter philosophy, a historian might consult economic data, and a novelist might draw upon anthropology. Libraries facilitate these unexpected connections.

6. Community Learning and Lifelong Education

Modern libraries host lectures, workshops, literacy programs, and research training. They support not only scholars but entrepreneurs, job-seekers, immigrants, and curious citizens. Knowledge advancement is not confined to academia; it thrives wherever informed communities gather.

7. Quiet Resistance to Intellectual Decline

In an age dominated by fleeting digital content and algorithm-driven information, libraries stand as bastions of depth, patience, and critical thinking. They encourage slow reading, rigorous citation, and evidence-based reasoning—habits essential for serious scholarship.

History offers many parallel examples: scientists drafting foundational theories in reading rooms, novelists shaping literary movements amid stacks of books, reformers grounding social change in archival research. None of these contributions could have been measured in advance by short-term performance indicators.

Ultimately, the value of a library lies not in how many books leave its shelves, but in how many minds leave transformed. It is less a warehouse of volumes and more a workshop of civilization, where ideas are forged, challenged, preserved, and reborn across generations.

Emerging Scenario- Not a pretty picture, is it?

The near exit of the British Council Library from most Indian cities is therefore not just an administrative or financial decision; it represents a cultural loss. It signals the erosion of shared spaces dedicated to learning for its own sake, especially at a time when thoughtful reading and sustained engagement with ideas are more necessary than ever.

As Chennai lost its British Council Library, one cannot help but feel a sense of nostalgia mixed with concern—for what has already been lost, and for what future generations may never experience. The hope remains that institutions, policymakers, and civil society will recognise the enduring value of libraries and work to preserve, revive, or reimagine them as essential pillars of an informed and reflective society.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.