“ऐ ग़म–ए–ज़िंदगी… कुछ तो दे मशवरा…

एक तरफ़ उनका घर… एक तरफ़ मैकदा।”

When Pankaj Udhas renders this couplet, the ghazal does more than mourn love—it stages a philosophical trial. The speaker is suspended between two irreconcilable goals: intimacy and intoxication, commitment and escape, responsibility and release. Classical Urdu poetry has long understood what modern decision theory formalizes only belatedly—that the tragedy of choice lies not in ignorance, but in awareness. One knows too much to choose easily.

This structure of anguish is neither accidental nor merely aesthetic. It is the same existential geometry that animates Hamlet’s soliloquy, Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, and Sartre’s insistence that freedom is a burden rather than a blessing. To choose is to negate; to affirm one path is to extinguish another. Every act of being is simultaneously an act of non-being.

Recast in the idiom of the twenty-first century, the verse mutates seamlessly:

“ऐ ग़म–ए–ज़िंदगी… कुछ तो तस्वीर साफ़ करा…

एक तरफ़ रूस का तेल… एक तरफ़ यूएस खड़ा…”

The beloved’s house and the tavern now stand for oil tankers and alliance structures, pipelines and press briefings, energy security and strategic signalling. Yet the dilemma remains ontologically identical. What has changed is scale, not substance. The intimate tragedy of the self has become the structural tragedy of the state.

Literature and the Universality of the Dilemma

Literature has always anticipated political economy. From Sophocles’ Antigone, where moral law collides with political authority, to Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, where faith, reason, and power tear the human psyche apart, the central insight is consistent: there are situations in which all available choices are compromised.

Urdu poetry, in particular, refuses resolution. The ghazal does not culminate in synthesis; it lingers in tension. This is profoundly anti-Hegelian. There is no Aufhebung, no neat transcendence. The pain is not a problem to be solved but a condition to be endured. In this sense, the ghazal is closer to Isaiah Berlin’s notion of value pluralism—the idea that ultimate human values are many, conflicting, and incommensurable. Liberty may clash with equality; justice with mercy; sovereignty with welfare.

International politics, like poetry, inhabits this tragic register.

Philosophy: Existential Choice and Moral Non-Idealism

At its philosophical core, this dilemma rejects moral absolutism. Kant’s categorical imperative—act only according to maxims that can be universalized—falters in a world where universality itself is asymmetrically enforced. Nietzsche saw this clearly: morality, when abstracted from power, becomes a tool of domination rather than emancipation.

Contemporary political philosophy responds with non-ideal theory, articulated by thinkers such as John Rawls (in his later work) and Amartya Sen. Non-ideal theory accepts injustice, coercion, and constraint as permanent features of human arrangements. The question shifts from “What is perfectly just?” to “What is less unjust, given where we stand?” It’s in this overarching context that we find the concepts of “horizontal equity” and “vertical equity” and “lesser evil” commonplace and resonating the world over.

India’s geopolitical predicament is precisely such a non-ideal situation. It is not choosing between good and evil, but between competing goods under constraint: affordable energy versus diplomatic pressure; strategic autonomy versus alliance credibility; domestic welfare versus external approbation.

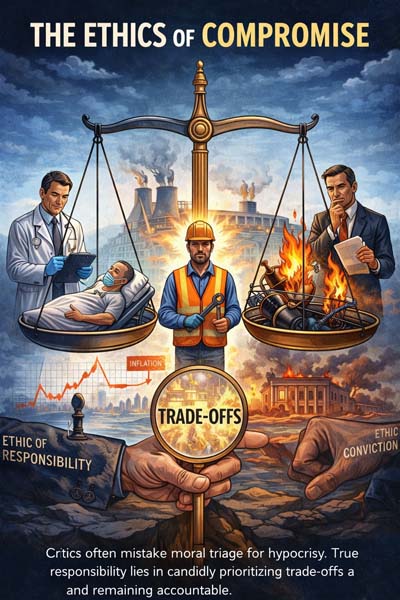

Economics: The Theory of the Second Best as Political Wisdom

Here, welfare economics provides more than technical insight; it offers philosophical realism. The Theory of the Second Best (Lipsey and Lancaster, 1956) dismantles the comforting linearity of optimization. If one Pareto condition cannot be satisfied—say, free and distortion less global trade—then satisfying the remaining conditions does not necessarily improve welfare. Indeed, it may worsen it.

Translated into political economy, sanctions are distortions; power asymmetries are distortions; security externalities are distortions. When these cannot be eliminated, insisting on textbook “optimal” behaviour, such as ideological purity or alliance conformity, may be welfare-reducing.

Thus, buying discounted Russian oil is not a violation of norms but a second-best correction in a distorted global system and stem from the compulsions of the domestic macroeconomic setting. Strategic ambiguity, selective alignment, and transactional diplomacy are not moral failures; they are responses to structural imperfection.

Adam Smith himself was no naïve free-marketeer. He understood that states operate under conditions of rivalry, fear, and scarcity. Economic rationality, in this sense, is not amoral; it is tragically moral, forced to choose the lesser loss.

International Relations: Tragedy, Not Hypocrisy

Classical Realism, from Thucydides to Hans Morgenthau, begins with a bleak but honest premise: international politics is governed by necessity, not virtue. The Melian Dialogue is instructive not because it endorses power, but because it exposes the futility of moral appeals in an anarchic system.

Structural realists like Kenneth Waltz go further: states do not choose freely; they respond to systemic pressures. To expect India to behave as if it inhabits a world of benign interdependence is to misread the distribution of power.

At the same time, pure realism is insufficient. India’s actions are not merely reactive; they are calibrated through domestic democracy, developmental imperatives, and civilizational memory. This produces what might be called strategic pluralism—the refusal to reduce foreign policy to a single axis of loyalty in an era at once of rising multipolarity and increasing inter-dependencies and inter-linkages revealing the quintessential truth of Nobel Laureate Ernest Hemingway’s insightful observation about “islands in the stream”.

Non-alignment, in its contemporary avatar, is not indifference; it is an assertion that autonomy itself is a value worth preserving, even at reputational cost.

The Ethics of Compromise

What critics often label as hypocrisy is, under closer inspection, ethical triage. In medicine, triage does not deny care; it prioritizes survival under scarcity. Similarly, states confronted with energy shocks, inflationary pressures, and security threats must rank harms rather than eliminate them.

To demand moral perfection from actors embedded in imperfect systems is not ethical rigor; it is moral exhibitionism. Worse, it risks what Max Weber warned against: an “ethic of conviction” divorced from an “ethic of responsibility.”

True responsibility lies in acknowledging trade-offs in a refreshingly candid assessment, absorbing their costs consciously, and remaining accountable for their consequences.

Conclusion: Living with the Sorrow of Choice

The ghazal does not end with resolution. Nor does Hamlet act without bloodshed. Nor do states navigate geopolitics without residue—resentment, suspicion, regret.

What matters is not the elimination of anguish, but its comprehension.

To understand why one chooses Russian oil over diplomatic comfort or strategic autonomy over moral applause is to honour the intelligence of constraint. It is to accept that life, like politics, is lived not in the realm of first-best fantasies but in second-best realities.

In such a constrained world, a world of imperfections, wisdom does not consist in choosing the pure path; it consists in choosing with eyes open, with an acute awareness of strategic options and choices on the table and the perception of “national interest”- howsoever loosely defined. For unlike the language of the software, there are no binaries here; we transcend 0 and 1 to arrive at a more nuanced view with multiple hues and shades of grey- not just white and black.

I have long held and strongly articulated my conviction that countries act clearly in their “national interest”- an interest, which is not etched in stone but is dynamic in accordance with the needs and requirements of the period, the set of entrenched circumstances, the national and international financial architecture, the “military-industry” complex and a system of stratification within and across geographies.

For the real tragedy is not that choices are imperfect— but that they are made without understanding the dilemma that made them inevitable. Hence, the choices must be made carefully and wisely lest the process and pattern of development be debilitated in a manner, which makes recovery difficult. Saner counsels must prevail in an environment of constant change and churn, volatility and turbulence. Res ipsa loquitur (Latin for “the thing speaks for itself”) is a tort law doctrine, which emphasizes that sometimes, circumstantial evidence can be powerful enough to shift the burden of proof. I rest my case.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.