There are journeys one plans with calendars and reservations, and there are journeys that begin quietly — almost invisibly — in the deeper corridors of memory.

Mine began in the familiar precincts of Navyug School in Delhi, where I had once been a student and where, after retirement, I had fallen into the habit of occasionally returning. Schools possess a strange permanence; even when buildings change and generations move on, something of one’s formative self lingers in their courtyards.

Navyug was shaped by the formidable yet deeply humane vision of Shri Jeevan Nath Dar — an educationist who believed that learning must extend beyond textbooks into the shaping of character, temperament, and perception. Long before educational philosophy rediscovered the importance of environment, Dar Sahib had already embraced it. He was also among the founding Principals of Netarhat Residential School, established on the ancient gurukul model — where the proximity of teacher and student mirrored the proximity of human life to nature.

During one such visit to Navyug, as I watched students disperse after morning assembly, a thought arose with surprising force:

If Dar Sahib invested his educational imagination in Netarhat, what kind of place must it be?

That question soon became a journey. And that journey became an inquiry — not merely into a destination, but into the future of tourism in Jharkhand.

The Ascent to Stillness

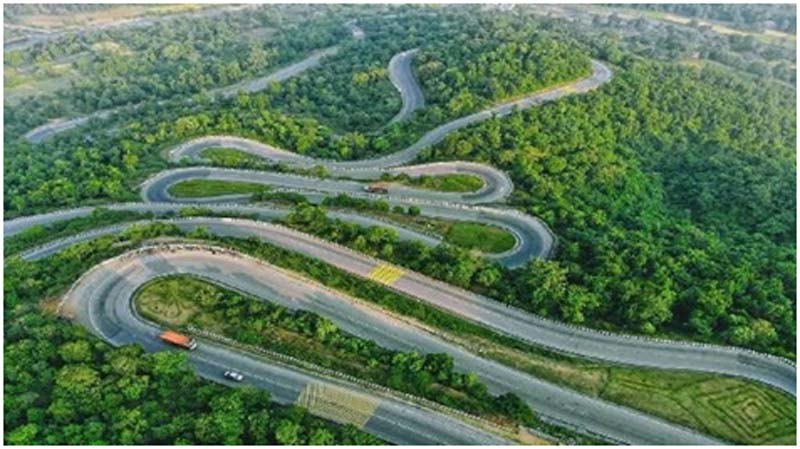

The road to Netarhat does not announce itself dramatically. It rises with composure, as though reluctant to disturb the forests it traverses. Gradually the plains loosen their hold, the air cools, and the horizon begins to ripple into hill upon hill.

Nothing about Netarhat is theatrical. There are no flashing promenades, no impatient marketplaces, no visual excess clamouring for attention. Instead, there is space — physical, psychological, almost philosophical.

Standing at Magnolia Point at dusk, watching the sun dissolve behind layered silhouettes of forested ridges, I felt a rare sensation in contemporary travel: permission to slow down.

And it was there that a larger question emerged:

What if the future of tourism belongs not to acceleration — but to deceleration?

In an age defined by velocity, Netarhat offers the counterintuitive luxury of unhurriedness. It is not merely a hill station. It is a meditation on tempo.

The Idea of Slow Tourism

The phrase “slow tourism” is sometimes mistaken for a niche preference. In reality, it may well represent the next evolutionary stage of travel.

Across the world, travellers increasingly seek immersion rather than itineraries, silence rather than spectacle, and renewal rather than distraction. Netarhat appears almost pre-adapted to this shift. Unlike many hill economies that succumbed to the seduction of rapid commercialization — often at severe ecological cost — Netarhat still retains what economists might call scarcity value.

Scarcity, in tourism, is not a limitation. It is a form of capital.

What struck me most was not simply the beauty of the plateau but the strategic possibility it embodied: Jharkhand could become the Eastern capital of slow, high-value tourism — if it chooses foresight over frenzy.

A State Misread

Jharkhand is frequently narrated through the vocabulary of minerals, industry, and extraction. Yet geography tells a more nuanced story.

Forests stretch across significant portions of its terrain. Waterfalls erupt dramatically from rocky escarpments. Sacred hills draw pilgrims upward in acts of devotion. Tribal cultures preserve ecological wisdom refined over centuries.

And yet tourism here remains less a failure of assets than a failure of articulation. The state does not suffer from a shortage of destinations. It suffers from the absence of a unifying narrative. Consider, for instance, the wilderness that waits quietly in the West.

The Forest That Does Not Perform

Within the expanse of the Palamu Tiger Reserve lies Betla National Park — a landscape that evokes a form of wilderness increasingly difficult to encounter.

Here, the forest does not stage itself for the visitor. One senses instead that entry must be negotiated with humility.

Wildlife tourism worldwide has demonstrated a consistent pattern: it encourages longer stays, deeper engagement, and higher local economic multipliers than hurried sightseeing.

Betla possesses all the ecological grammar required to evolve into Eastern India’s signature wilderness — provided its development is guided by science rather than impatience.

For forests, more than most landscapes, are slow teachers. They reward restraint and punish haste.

When Water Becomes Memory

If Betla speaks in whispers, Hundru Falls speaks in thunder.

Fed by the Subarnarekha River, the waterfall plunges nearly a hundred meters in a spectacle that requires no interpretation. Tourism theorists often refer to such landscapes as carriers of instant awe — places where emotional response precedes cognition.

States are sometimes defined by a single enduring image. Hundru has the potential to become that image for Jharkhand.

Yet the management of such power must be disciplined. Viewpoints must respect the natural skyline; visitor flows must be regulated; infrastructure must assist without intruding. For once visual dignity is compromised, recovery is rarely swift.

The Strategic Moment Before the Surge

India’s established hill destinations offer an instructive caution. Rapid tourist inflows brought prosperity but also traffic paralysis, water stress, architectural chaos, and ecological fatigue.

Jharkhand stands at a more forgiving historical juncture — one in which it can learn without first enduring the damage.

The temptation for emerging destinations is almost universal: pursue numbers. But numbers alone seldom build durable tourism economies. A wiser doctrine would be simple: Value per visitor must exceed volume of visitors.

The Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan demonstrated the viability of this approach by deliberately privileging high-value travel while safeguarding cultural and environmental integrity. Crowding is not a sign of success if it erodes the very experience travellers seek. Once a destination becomes ordinary, reclaiming its mystique is extraordinarily difficult.

Climate, Fatigue, and the Traveller of Tomorrow

Look ahead a decade and a pattern becomes visible. Urban India is heating — meteorologically and psychologically. Summers lengthen, megacities grow denser, and the search for breathable landscapes intensifies.

The traveller of the future may not ask merely, “Where can I go?” The deeper question will be, “Where can I recover?” Elevated plateaus, forest microclimates, and low-density geographies will command growing attention. In that emerging map, Jharkhand is not peripheral. It is strategically placed. The state should resist the urge to become the most visited. It should aspire instead to become the most remembered. Memory, after all, is the strongest engine of return.

Imagining Jharkhand, 2036

What might the state look like if guided by long-horizon thinking? One can imagine a three-tier tourism architecture emerging with clarity.

- First, globally recognizable landscapes — Netarhat as an eco-wellness plateau, Parasnath Hill as an international spiritual ascent, Betla as a respected wilderness brand.

- Second, a scenic engine composed of waterfalls, valleys, and cinematic drives that lend the state visual identity.

- Third, a network of cultural depth — tribal traditions, forest cuisines, craft lineages, and layered histories — creating emotional resonance rather than transient consumption.

Such a framework could position Jharkhand as:

- Eastern India’s premier wellness retreat zone.

- A preferred summer refuge.

- A model of climate-resilient tourism.

- One of the country’s most quietly respected destinations.

Not loud — but lasting.

The Danger Hidden Within Success

Paradoxically, the greatest threat to Jharkhand’s tourism future may arrive disguised as progress. Unregulated hotels, speculative land markets, and fragmented planning can degrade landscapes with surprising speed. Infrastructure, therefore, must learn the art of invisibility.

Eco-lodges rather than vertical hotels. Local materials rather than reflective glass. Skyline discipline rather than architectural improvisation. Prevention is always less painful than restoration. One might call this principle — only half in jest — avoiding the Shimla syndrome.

The Decisive Decade Ahead

Vision acquires meaning only when translated into execution. The coming ten years will likely determine whether Jharkhand matures into a model of sustainable tourism or drifts toward mediocrity. Several priorities appear self-evident. High-value landscapes should be designated as conservation zones before speculative pressures intensify. Access infrastructure — roads, medical readiness, emergency response — must precede accommodation expansion, for travellers forgive distance more readily than inconvenience.

Investment should concentrate on a few anchor destinations rather than dissipating across dozens of minor sites. Tourism grows through gravitational centres. Scientific carrying-capacity norms must guide visitor numbers. Scarcity, properly managed, enhances both ecological stability and economic yield. Private capital should be welcomed, but within firm ecological and architectural codes. Meanwhile, the state must cultivate a unified brand voice — one that communicates coherence rather than fragmentation.

Above all, Jharkhand must pivot from selling sights to curating experiences: forest immersion, cycling corridors, astronomy camps beneath low-light skies, silence retreats, spiritual treks. Increasingly, travellers seek not activity but transformation.

Tourism as Territorial Strategy

As these reflections gathered force during my stay, a deeper realization surfaced. Tourism is no longer merely an adjunct of hospitality. It is a form of territorial strategy. Regions that protect their landscapes today will shape mobility flows tomorrow. In an era of climate uncertainty, ecological stewardship is not simply ethical — it is economically prescient. Jharkhand still retains agency over its terrain. Few places are granted such a second chance.

Returning to the Plateau

On my final morning, I rose before dawn and stepped into the cool hush. The Eastern sky kindled slowly, and the plateau seemed to hover between darkness and illumination. In that suspended hour, I found myself thinking again of Shri Jeevan Nath Dar. Perhaps he understood, long before policy language attempted to capture it, that nature is not merely scenery. It is pedagogy. Netarhat does not hurry the visitor; it educates the visitor into unhurriedness.

And in doing so, it offers a metaphor for development itself — reminding us that progress need not always be loud, that restraint can be strategic, and that preservation is often the highest form of advancement.

The Luxury of Stillness

Jharkhand need not compete with crowded destinations. Its comparative advantage lies elsewhere — in cultivating distinction rather than imitation. For in tourism, as in culture, rarity commands reverence.

If the state chooses discipline over diffusion, value over volume, and foresight over frenzy, its forests and plateaus may yet become sanctuaries for a future India seeking pause.

Years from now, travellers standing at Magnolia Point may not only watch the sun descend beyond the hills. They may witness something rarer — the success of a region that recognized, early enough, that the ultimate luxury of the modern world is not excess. It is stillness. And in that stillness, perhaps, time itself learns to breathe.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry (Retd) is a social observer and writes on contemporary national and international issues, strategic implications of infrastructure development towards national power, geo-moral dimension of international relations and leadership nuances in changing social construct.

Lt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry (Retd) is a social observer and writes on contemporary national and international issues, strategic implications of infrastructure development towards national power, geo-moral dimension of international relations and leadership nuances in changing social construct.