India’s energy transition has entered a phase where scale, reliability, and decarbonisation must advance together. Rapid growth in electricity demand, increasingly binding climate commitments, and the limits of variable renewables have sharpened the search for clean, firm power. Against this backdrop, the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025, represents the most consequential overhaul of India’s nuclear governance framework since the Atomic Energy Act of 1962.

The Act consolidates legacy legislation, recalibrates institutional arrangements, and signals a decisive shift from a tightly centralised, state-dominated nuclear regime to a more investment-aware and execution-oriented model, while stopping short of full liberalisation. In doing so, The SHANTI Act, 2025, attempts to resolve a paradox that has long characterised India’s nuclear programme: proven technological capability, but persistently limited scale.

Why a New Nuclear Law Now?

India’s nuclear sector has historically operated under a fragmented legal architecture, anchored in the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010. These laws reflected the priorities of an earlier era, viz., strategic secrecy, technological self-reliance, and a near-complete state monopoly. While appropriate at the time, this framework has increasingly appeared misaligned with contemporary realities.

Despite decades of investment, nuclear power today contributes only about 3.1 percent of India’s electricity generation and less than 2 percent of installed capacity. Operational capacity stands at roughly 8.78 GW, with targets of 22.38 GW by 2031–32. More ambitiously, the government has announced a Nuclear Energy Mission to reach 100 GW by 2047, positioning nuclear energy as a pillar of India’s net-zero strategy.

The problem is not ambition, but execution. Time overruns, cost escalations, limited institutional bandwidth within the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL), and an investment-unfriendly liability regime have constrained expansion. The SHANTI Act, 2025 is an attempt to address these binding constraints through structural reform rather than incremental adjustment.

Opening the Sector: Without Diluting Sovereignty

The Act’s most politically sensitive feature is its calibrated opening of the nuclear sector to private participation, including equity participation of up to 49 percent in certain activities. Private entities are permitted to engage in reactor construction, plant operations, power generation, equipment manufacturing, and selected fuel-cycle activities, subject to licensing and regulatory oversight.

At the same time, the SHANTI Act, 2025 draws a clear red line around strategically sensitive domains. Spent fuel management, reprocessing, high-level waste handling, isotopic separation, and heavy water production remain exclusively with the Central Government or its wholly owned entities. This dual structure reflects a deliberate policy choice: mobilise private capital and execution capacity without compromising national security or strategic autonomy.

At the same time, the SHANTI Act, 2025 draws a clear red line around strategically sensitive domains. Spent fuel management, reprocessing, high-level waste handling, isotopic separation, and heavy water production remain exclusively with the Central Government or its wholly owned entities. This dual structure reflects a deliberate policy choice: mobilise private capital and execution capacity without compromising national security or strategic autonomy.

In effect, the Act breaks NPCIL’s monopoly over nuclear power generation while preserving the state’s control over the nuclear fuel cycle. The expectation is that competition among operators will improve project management, reduce delays, and impose greater cost discipline. These are the benefits that India’s single-operator model has struggled to deliver.

Strengthening Regulation and Safety Oversight

A second major reform lies in granting statutory status to the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB). Until now, the AERB functioned through executive authority, raising persistent concerns about regulatory independence in a sector where the state is both operator and overseer.

Formal statutory recognition enhances the AERB’s credibility, enforcement powers, and institutional autonomy. This is an essential prerequisite for scaling nuclear capacity and building public trust. The Act establishes a comprehensive licensing and safety authorisation regime covering the entire lifecycle of nuclear installations, from siting and construction to decommissioning.

The SHANTI Act, 2025 also introduces a multi-tier adjudication framework, spanning the AERB, a new Atomic Energy Redressal Advisory Council, the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity, and ultimately the Supreme Court. This architecture is designed to provide time-bound, technically informed dispute resolution, critical for investor confidence in a capital-intensive sector with long gestation periods.

Reworking Nuclear Liability: A Necessary Trade-off

Perhaps the most consequential and controversial reform is the overhaul of nuclear liability. The earlier regime, shaped by the 2010 Act, imposed an unusually stringent liability structure that deterred both domestic and foreign participation. The SHANTI Act, 2025 replaces this with a graded liability framework, differentiating operator liability based on reactor type and risk profile, and caps operator liability at around 300 million SDR (approximately ₹3,000 crore), with the government acting as a backstop.

This aligns India more closely with international practice and makes nuclear projects insurable and bankable. Yet the trade-off is explicit: in a catastrophic event, compensation would fall well short of total damages, shifting residual risk to the state. The SHANTI Act, 2025, thus prioritises investment viability over full internalisation of worst-case risks. This is a choice that reflects global norms, but not without ethical and political implications.

Beyond Electricity: Expanding Peaceful Applications

Importantly, the Act recognises that nuclear technology extends well beyond power generation. The Act establishes a regulatory framework for non-power applications in healthcare, agriculture, industry, and research, where radiation technologies are increasingly important. Limited exemptions from licensing for research and innovation signal an intent to encourage technological advancement rather than stifle it through over-regulation.

This broader framing aligns nuclear policy with India’s developmental priorities, rather than treating it solely as a strategic or electricity-generation asset.

The SMR Bet and the Execution Challenge

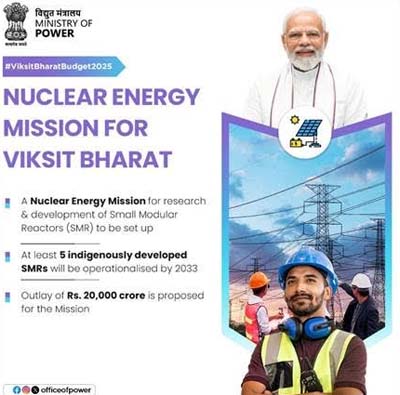

The SHANTI Act, 2025 dovetails with recent policy signals, including the ₹20,000 crore allocation in the Union Budget 2025–26 for Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). Indigenous designs such as the BSMR-200 and SMR-55, along with high-temperature reactors for hydrogen production, are projected as game-changers, with operational deployment targeted by 2033.

This is a high-stakes gamble. There is an eight-year vulnerability window during which private operators may opt for commercially available foreign SMR technologies, potentially locking India into imported designs, fuel dependencies, and supply chains. India’s experience to date, especially the delays associated with the Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor, raises legitimate scepticism about the timely indigenous delivery of advanced nuclear technologies.

Can Nuclear Deliver?

Even if the SHANTI Act, 2025 succeeds on its own terms, hard questions remain. Nuclear power remains costly, with tariffs of around ₹6 per unit, which are significantly higher than those of coal and solar. Full lifecycle costs, including waste disposal and decommissioning, are often understated. Public opposition, shaped by global accidents and domestic protests such as those at Kudankulam, continues to pose a serious political constraint.

Moreover, even 100 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047 would likely amount to only about 5 percent of India’s projected electricity capacity, given total capacity estimates exceeding 2,000 GW. Nuclear’s contribution would be meaningful, but not transformative on its own.

The only true wildcard is nuclear fusion. A commercial breakthrough would radically alter the economics, safety profile, and scalability of nuclear energy. While fusion remains unproven after decades of research, the SHANTI Act, 2025, at least ensures that India’s regulatory architecture would be better prepared should such a breakthrough occur.

Conclusion

The SHANTI Act, 2025, marks a structural shift in India’s nuclear policy, comparable in intent, if not in scope, to the economic reforms of the early 1990s. It removes long-standing legal and institutional constraints, modernises regulation, rationalises liability, and creates space for private participation without relinquishing strategic control.

Yet legislation alone cannot guarantee outcomes. Chronic execution delays, regulatory capacity limits, technology risks, and political resistance remain formidable. The Act creates the conditions for success, yet success is not assured. Whether the Act becomes a historic turning point or another missed opportunity will depend not on its text, but on implementation over the next decade.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Debesh Roy is Chairman, Institute for Pioneering Insightful Research Pvt. Ltd. (InsPIRE), a research and consultancy firm focused on policy-relevant work in economics and climate change. An economist and development professional with 38 years of experience, including over three decades at NABARD, he specialises in macroeconomic policy, agriculture, rural finance, and climate change.

Dr Debesh Roy is Chairman, Institute for Pioneering Insightful Research Pvt. Ltd. (InsPIRE), a research and consultancy firm focused on policy-relevant work in economics and climate change. An economist and development professional with 38 years of experience, including over three decades at NABARD, he specialises in macroeconomic policy, agriculture, rural finance, and climate change.