While President Trump goes after almost the entire comity of nations for his myopic, yet unattainable, lofty economic and political objectives, the Chinese have accelerated the pace of using trade and finance as weapons for furthering their strategic interests. The countries which the Dragon considers to have such value are being unmistakably favored in trade, investment, and financial aid, while those with disagreements or hostile public stances are at its receiving end.

Of late, the countries being favoured are Pakistan and Bangladesh, while India, engaged in a territorial dispute along its 3,500 km long northern and eastern borders since the early Sixties, finds tariffs and a host of non-trade barriers being used against it periodically. Among the merchandise being discriminated against in recent months is diammonium phosphate (DAP), a chemical-based fertilizer applied before sowing. While domestic shortage in China is cited as the reason for cutting off exports to India, its two neighbours continue to receive the critical input. Similarly, while Indian rice has been subjected to severe import restrictions, no such curbs are imposed on exports from either of the two nations.

The Chinese FDI inflows, significant in other South and South Eastern Asian nations, are marginal and shrinking when it comes to India. The cumulative US $3 billion from China thus far is matched by Indian investment over the years, in China. The pre-inflow permission requirement upon all neighbours with land borders, imposed by India in 2020, has further reduced Chinese investment. Understandably, there are no China-grant projects. The checking of FDI, however, has had the concomitant impact of reducing inflows of technology and management skills into India, while the trade-related impositions have had wider adverse economic and financial consequences.

It is worth noting that China is no longer an exporter of only low-technology goods with comparative advantage based on cheap labour and economies of scale. With concerted efforts, especially over the last two decades, it has turned itself into a global leader in AI, robotics, blockchain, and automation. With about 22,000 industrial robots deployed in 2023—the most in any country—it has overcome the labour shortage that arose from following the single-child policy for almost two generations. Alongside, it has been contracting out labour-intensive manufacturing to neighbours like Vietnam and, more recently, Malaysia and Indonesia, all highly populated countries. Trade agreements, FDI, and financial assistance to create industrial and social infrastructure are being liberally used to lure them.

Using its supply dominance to hurt India

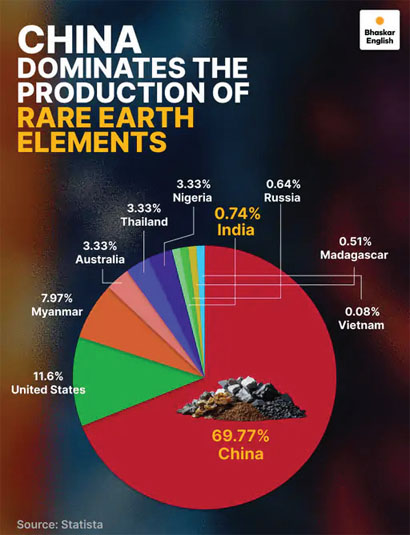

The trade data shows that Sino-India bilateral trade, in fact, has been on the rise despite the more frequent intrusions across the Indian border since the Galwan clashes in 2020. The trade deficit with China is increasingly becoming pronounced. Last fiscal year, it almost hit the US $100 billion mark. This was as much due to the already meagre Indian exports declining to a paltry $15 billion as it was due to imports from China remaining high, totaling around $115 billion. Indian exports of textiles, iron ore, rice, and others have been decreasing for a variety of reasons, including deliberately imposed Chinese trade barriers. On the other hand, despite conscious Indian efforts to check imports and promote the Make in India mission, dependency on Chinese imports remains unacceptably high. It varies from 100% of aggregate imports of certain critical rare earth minerals, solar cells, and APIs for drug formulation, to about a third in other segments like industrial chemicals and plastics.

Of the much-talked-about electronics sector, whose exports from India last year topped $40 billion, imports of electronic end-products, components, and raw materials remain above the $100 billion mark. Their import share from China is still around 40%, about the same level as in 2010–11. This predominantly consists of essential rare earths as well as several end-products. Apple, though shifting production of some products to India—especially iPhones—faces the twin challenges of Trump’s higher tariffs on phones produced in India and Chinese curbs on the supply of critical rare earths. Hitherto, India has concentrated on final assembly but remains dependent upon core designing undertaken in the US, LCDs and microchips produced in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and several end-products from China and Vietnam.

Of the much-talked-about electronics sector, whose exports from India last year topped $40 billion, imports of electronic end-products, components, and raw materials remain above the $100 billion mark. Their import share from China is still around 40%, about the same level as in 2010–11. This predominantly consists of essential rare earths as well as several end-products. Apple, though shifting production of some products to India—especially iPhones—faces the twin challenges of Trump’s higher tariffs on phones produced in India and Chinese curbs on the supply of critical rare earths. Hitherto, India has concentrated on final assembly but remains dependent upon core designing undertaken in the US, LCDs and microchips produced in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and several end-products from China and Vietnam.

The recent imposition of a licensing requirement for export of seven rare minerals required for magnet-making—of which China is almost a monopoly—has globally upped the ante for missile manufacturers, electric vehicle makers, precision equipment assemblers, and windmill producers. That includes India-based ones. With more than a 90% share of global production and processing of rare earth elements, alongside the manufacturing of magnets, China’s ability to distort availability and cost of end-products has become threateningly high. Its leadership seems to be resorting to such tactics consciously, leveraging its supply dominance.

For a variety of plastics, industrial chemicals, and active pharmaceutical ingredients needed by thousands of drug formulators (both large and MSMEs, especially generics) the reliance on China remains excessively high. For example, the future of India’s rapidly expanding solar power industry remains inextricably linked to competitively priced imports of cells and panels. China, the world’s largest oil importer, while striving to reduce its crude oil imports of 11 million barrels per day, is putting vast efforts and resources into expanding its renewable and electric vehicle industries.

With considerable state support, about 500 companies in China make EVs or their components. Battery manufacturing is being encouraged with heavy subsidies. Public electric charging points already number about 14 million—nine times more than in the USA. Last year, government agencies at various levels invested $7 billion in associated R&D. The stated national objective is to make EVs cost about $10,000 each, capable of charging- in under five minutes, with a driving range of 800 km. However, such altruistic goals could compel the Chinese establishment, in the not-too-distant future, to consider checking the export of solar cells and associated materials. Unless new technologies to capture solar energy are developed concurrently, the Chinese could virtually choke off solar-based renewable energy development in India and several other countries.

With considerable state support, about 500 companies in China make EVs or their components. Battery manufacturing is being encouraged with heavy subsidies. Public electric charging points already number about 14 million—nine times more than in the USA. Last year, government agencies at various levels invested $7 billion in associated R&D. The stated national objective is to make EVs cost about $10,000 each, capable of charging- in under five minutes, with a driving range of 800 km. However, such altruistic goals could compel the Chinese establishment, in the not-too-distant future, to consider checking the export of solar cells and associated materials. Unless new technologies to capture solar energy are developed concurrently, the Chinese could virtually choke off solar-based renewable energy development in India and several other countries.

An equally worrisome issue is China’s ability to choke the Indian technology supply chain. A fortnight ago, it compelled its citizens working in Apple’s Indian phone assembly and Foxconn’s component-making facilities to return to China. Causing disruption in the production lines is clearly aimed at hurting India’s competitiveness and exports. First, it was attempted by placing restrictions on sales of high-tech capital equipment, then by limiting exports of critical rare earths, and now by withdrawing personnel supervising the iPhone assembly process. Mobile phone exports last year had soared to $32 billion from $24 billion a year earlier. Such unfriendly acts could also be extended to other electronic items exported from India, though the local value added in many of them is still low, leaving room for further development.

A potential choke point in the offing is China’s construction of a five-layered storage-based hydropower project in the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra River. Though located in Tibet, now an integral part of China, this upper riparian state has not entered into any water management or sharing arrangement with any of the lower riparian nations, including India. In fact, China has no water-sharing pact for any of the rivers originating or passing through its territory, with any of the dozen countries it borders. Blocking the downward flow of water from the mighty Brahmaputra into India’s northeastern states can cause unimaginable human and economic distress. Worse would be the consequences of the deliberate or even accidental release of sizable quantities of water stored at height.

Exploring ways & means to immune itself from Chinese maneuvers

It needs to be accepted that China has gone about systematically and assiduously building its comparative advantages since it opened itself to foreign trade, investment, and technology. The choice of fields of concentration was determined by its strategic interests, both existing and future. There have been sufficient indications to conclude that China seeks to be the hegemonic superpower of Asia and the Indo-Pacific region, and it sees India as a contender in South Asia. India’s history, size, population, and economic potential bother it far more than it admits.

Another recognition is that China, through diligence, patience, and manipulation, has turned itself into the second-largest economic superpower, with a per capita income four times higher than India’s. It has become the world’s largest trader and a nuclear and conventional power of consequence. Its naval prowess matches the USA’s, while its air force squadrons are twice the number of India’s. Despite India’s Neighbourhood First Policy and Look East orientation, China has succeeded in creating around India a ‘string of pearls,’ or countries favourably disposed towards it. This geopolitical situation, combined with the huge differential in economic and military strength, must be accounted for when devising measures to counter China’s hegemony.

It is not being suggested that India can’t lower its economic dependence on China, but rather that the entire exercise demands concerted and well-thought-out measures that will yield results gradually. Several countries, including developed ones, face similar limitations as India in the availability of rare minerals and magnets. Collectively, they can better handle Chinese supply-oriented dominance. The Foreign Ministers of the four Quad countries, a fortnight ago, resolved in Washington to address this issue. Earlier in February, Prime Minister Modi and President Trump had identified it as a segment for cooperation and joint action. India has already launched efforts to collaborate with several African and Latin American nations to explore, mine, and process minerals. Greater success is possible by giving mineral-bearing nations a meaningful stake in ventures. Combining this with “soft power assistance”—such as education, healthcare, and other essential services for local residents—should be an integral part of the strategy.

Going beyond China in trade matters can be partially tackled by India giving up its hesitation to enter new bilateral trade pacts. Currently, there are only a handful of such agreements in force between India and other nations. The recent limited deals with the UAE and Australia have resulted in notable mutual benefits and encouraged India to re-explore engagements with EFTA and the UK. In a rapidly changing global trade environment—where the WTO is weakening in its ability to push a rules-based regime—bilateral and multilateral regional pacts are the way forward. India, which has internally put in place a standard operating procedure for trade negotiators, may need to grant them greater flexibility to strike deals. That would shorten the time required for finalization and help repudiate the impression in the developed world that India procrastinates and raises too many red flags. Freer trade with lower tariffs should certainly help Indian manufacturers and service providers gain entry into global supply chains with a China plus characteristic.

On its own, India would need to ensure that imports of non-essentials from China are eliminated, even if those items are cheaper than locally produced alternatives. Alongside, a specific and substantially state-funded R&D effort aimed at developing domestic substitutes for Chinese imports has to be initiated. Unlike the PLI scheme, which has multiple end objectives and a shorter terminal date for receiving monetary benefits, the subsidy and support for this initiative must be singularly focused and extended over a longer horizon.