In his Independence Day address from the ramparts of the Red Fort in Delhi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the government’s intention to revisit the Goods & Service Tax (GST) regime. Introduced in mid-2017 to create a countrywide common market by unifying multiple indirect taxes at the central and provincial levels the review, which has already been set in motion, aims to simplify the tax setup, provide palpable relief to the common man, and minimize the unintended distortions. In the context of the global economic and financial turmoil underway, lowering the incidence of taxation is expected to soften the impact by putting more disposable income in the hands of consumers to spend.

That the Union government means business and expects to usher in the revised GST by Diwali, the occasion promised by the Prime Minister, is evident from the promptness of action at various levels. While a team of his advisers has shortlisted the action items for what is being loosely called the second-generation reforms, the required modifications in GST have been zeroed in on by a Group of Ministers (GoM). To finalize them on September 3rd and 4th, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has convened a meeting of the GST Council — the highly effective joint Centre-State mechanism, to frame the amended scheme. To reach such an advanced stage within a week of making the intention known may be a record in public policy. It reinforces the clichéd but accurate adage ‘where there is a will, there is a way.’

The Rationale behind the Revision and the New Proposal

The extant GST had rightly done away with the cascading effect of the earlier tax regimes and has steadily helped garner higher revenues — in the last fiscal year, it averaged Rs.1.58 lakh crores a month, up from Rs.92,500 crores in its first year, despite a somewhat lower than the envisaged GDP growth of 6.5% in 2024–25. However, the growing impression is that the tax rates are too high, and the compliance process is still onerous with the system having created an atmosphere of fear rather than trust. Together, these factors have impacted the ease of doing business and acted as a disincentive to entrepreneurship.

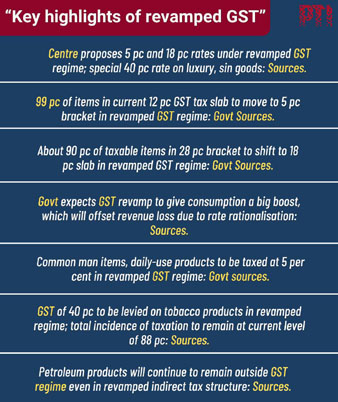

Addressing such apprehensions cannot be delayed for too long lest the spiral of lower growth perpetuates itself. With exports of both merchandise and services likely to remain under pressure for some time, our domestic orientation will need to be accentuated. Through the intended rationalization, specifically reducing the current four slab rates of 5%, 12%, 18% and 28% to just two, with essential and daily-use items taxed at 5% and all others at 18% (while “sin goods” including luxury items face item-wise hikes up to 40%), the average tax rate will decline from 11.64% to below 10%. According to State Bank of India estimates, such a move could increase consumption in the economy by a staggering Rs.2 trillion, or 8% of household demand. With aggregate consumption exceeding the current 60% of GDP, tax-optimization has the potential to spur both manufacturing and services. Taken in combination with the existing corporate tax rate of 25%, this measure should also improve the country’s global competitiveness.

Addressing such apprehensions cannot be delayed for too long lest the spiral of lower growth perpetuates itself. With exports of both merchandise and services likely to remain under pressure for some time, our domestic orientation will need to be accentuated. Through the intended rationalization, specifically reducing the current four slab rates of 5%, 12%, 18% and 28% to just two, with essential and daily-use items taxed at 5% and all others at 18% (while “sin goods” including luxury items face item-wise hikes up to 40%), the average tax rate will decline from 11.64% to below 10%. According to State Bank of India estimates, such a move could increase consumption in the economy by a staggering Rs.2 trillion, or 8% of household demand. With aggregate consumption exceeding the current 60% of GDP, tax-optimization has the potential to spur both manufacturing and services. Taken in combination with the existing corporate tax rate of 25%, this measure should also improve the country’s global competitiveness.

The rationalization-process of GST, however, must be completed at the earliest and the revisions effected soon thereafter. With Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations, the festive season which lasts until Diwali on October 20th, has set in. Both vendors and buyers eagerly await GST relief. In the meantime, they are likely to postpone transactions in durables and white goods. Any delay in implementing the lower rates could further dampen the already sluggish demand.

Global experience shows that higher tax rates and administrative complexities rarely sustain robust collections. The incentive to avoid or evade tax remains strong. India’s own fiscal history is no different: levying direct taxes as high as 98.5% of income in the 1970s and earlier decades neither raised revenue nor expanded the tax base. Only after their reduction to affordable levels, coupled with a broader base of taxpayers, did the tax accruals get augmented .

Eight years of GST also bear this out, though there is clearly room for further progress. Rampant avoidance routinely by petty shopkeepers through declining to issue bills or receipts, continues to erode the collections in both metros and rural areas. It also leads to a noticeable black market for goods and services. Substantially reducing rates, and eventually adopting a single, uniform rate as seen in most developed countries, would be ideal.

Eight years of GST also bear this out, though there is clearly room for further progress. Rampant avoidance routinely by petty shopkeepers through declining to issue bills or receipts, continues to erode the collections in both metros and rural areas. It also leads to a noticeable black market for goods and services. Substantially reducing rates, and eventually adopting a single, uniform rate as seen in most developed countries, would be ideal.

That said, we must also face our current reality; with a large portion of India’s population at the bottom of the pyramid or in the lower middle class, there is a need to continue exempting several essential daily-use items and taxing several others at no more than 5%. The latter should include almost all industrial raw materials, as well as health and life insurance. Whether the extensive low-cost housing should also be brought under GST at a 5% rate remains a moot point. The higher category of 18%, which is a rather steep rate, should apply only to goods, services, and amenities generally consumed by the upper-middle class. It must be the exception, not the rule. Only then will the goal of boosting domestic consumption be served. Stepping up the tax burden on luxury and “sin goods” such as tobacco products and alcohol to 40% and beyond could, to some extent, offset the revenue losses caused by the rationalization.

Getting the States On-board

For almost every state in the Union, accruals from GST collections constitute their single largest source of revenue. Yet, they continue to seek additional funds from the Centre. Some of them even feel that the Centre has benefitted disproportionately since the guaranteed compensation to the states ceased on July 1, 2022, while the levy of the Compensation Cess was extended until March 2026. In reality, this extension was justified: collections from the cess during the COVID-19 pandemic had sharply declined, forcing the central government to borrow funds to honour its compensation commitments to the states.

With the private sector still wary of fresh investments, states have increasingly stepped-up efforts in capital-intensive infrastructure creation, along with better provision of essential services such as healthcare, education, and social security. Recently, their demands for additional funds have grown louder as rising global protectionism – led by President Trump – has begun to adversely affect export-oriented ventures within their jurisdictions. The need for state-level ameliorative actions and relief for displaced workers is becoming urgent; for example, 1.5 lakh workers in the Surat diamond polishing industry face imminent layoffs, while several cancellations of export orders for apparel and leather goods in Tamil Nadu have also been reported. Such developments are being actively highlighted by exporters and political leaders across Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh.

Paying heed to the states’ concerns is essential under the statutorily mandated GST Council framework. For any agenda item to be approved, a two-thirds majority of votes is required. The Centre and the states together hold 50% weightage each. Consequently, neither side — even if all states were united — can pass an item on its own. Moreover, given the states relinquished their individual rights over indirect taxation (despite these being constitutionally vested in them), it would be fair for their evolving demands and proposals to be treated with due consideration.

In this context, it may become necessary to evolve ways and means to assure the revenue share of the states, even if the overall collections unexpectedly decline under the rationalised GST structure. While most projections are positive, a few pessimistic accountants estimate that the proposed modifications could cause an annual shortfall of Rs.45,000 to Rs.50,000 crores on the downside. While significant in absolute terms, such a figure is not beyond the Centre’s capacity to manage.

The highly desirable reform of GST could well serve as the torchbearer for a broader range of economic and financial reforms in India. The buoyancy in economic performance over the last few years – which has propelled India to the position of the world’s fastest-growing large economy, soon on track to becoming the third largest – must be sustained through timely, consensus-driven actions. Irrespective of political hues or affiliations, the states remain the fulcrum upon which the prosperity and well-being of 1.45 billion Indians, a population larger than that of North America, all of Europe, and Australia combined, will ultimately depend.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Ajay Dua is a former Union Secretary, Commerce & Industry and a development economist by training.

Dr. Ajay Dua is a former Union Secretary, Commerce & Industry and a development economist by training.