Unencumbered by having to defend Britain, the great American historian Will Durant asked his Western readers in 1931 to remember that,

India was the mother-land of our race, and Sanskrit the mother of Europe’s languages; that she was the mother of our philosophy; mother, through the Arabs, of much of our mathematics; mother, through Buddha, of the ideals embodied in Christianity; mother, through the village community, of self-government and democracy. Mother India is in many ways the mother of us all.1

While seemingly hyperbolic, he was right that ‘It was to reach this India of fabulous riches that Columbus sailed the seas’2. In 1817, James Mill wrote a polemical book, The History of British India, that became the bible for all Britons coming out to India. Mill wanted to show that Britain had taken control of a barbaric and primitive country that Britain needed to civilize. He dismissed the knowledge of the depth and breadth of India’s intellectual legacy that genuine scholars like William Jones had discovered.

While seemingly hyperbolic, he was right that ‘It was to reach this India of fabulous riches that Columbus sailed the seas’2. In 1817, James Mill wrote a polemical book, The History of British India, that became the bible for all Britons coming out to India. Mill wanted to show that Britain had taken control of a barbaric and primitive country that Britain needed to civilize. He dismissed the knowledge of the depth and breadth of India’s intellectual legacy that genuine scholars like William Jones had discovered.

James Mill knew no Indian language and had never visited India, but he firmly discarded the idea that Indians could have discovered zero and the decimal system, or the facts that the Earth is round, rotates and revolves around the sun (rather than the other way round) — all ideas that Aryabhata had discovered by 499 CE, many centuries before they reached Europe. Indeed, Aryabhata had discovered gravity nearly 1,200 years before Isaac Newton’s famous apple moment. But James Mill asserted that all this must have been learnt by modern Indian pandits from books written by Europeans, and passed off as ancient Indian knowledge!

Mill’s notion of India, sadly, is the standard perception that pervades the English-speaking world, all the way to the drawing rooms of Lutyens’ Delhi. So, Fibonacci (of the famous number sequence, which had been discovered a millennium earlier by Pingala in the Gupta era) acknowledged in the preface to his own book Liber Aci (1202) his deep debt to the ‘Indian method’ of mathematics (Modus Indorum), compared to which Pythagoras was ‘almost erroneous’, but the West knows little of this legacy. Getting past the fog of Mill’s obfuscation remains a herculean task. Will Durant’s book was banned in British India immediately after it was published in 1931, and did not become available again until it was republished by a private Indian book store in 2007.

Mill’s notion of India, sadly, is the standard perception that pervades the English-speaking world, all the way to the drawing rooms of Lutyens’ Delhi. So, Fibonacci (of the famous number sequence, which had been discovered a millennium earlier by Pingala in the Gupta era) acknowledged in the preface to his own book Liber Aci (1202) his deep debt to the ‘Indian method’ of mathematics (Modus Indorum), compared to which Pythagoras was ‘almost erroneous’, but the West knows little of this legacy. Getting past the fog of Mill’s obfuscation remains a herculean task. Will Durant’s book was banned in British India immediately after it was published in 1931, and did not become available again until it was republished by a private Indian book store in 2007.

In the first sixty years after Plassey, the British had sought to assimilate into the local milieu (as the Mughals Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Dara Shukoh did, and the Portuguese afterwards) with several early luminaries of the Company marrying Indian women and becoming effectively Indianized. Warren Hastings (the first governor general of British India) was fluent in Bengali and Farsi, was acquainted with Hindu and Muslim scriptures, and admired India’s culture and history.

Several early judges and administrators were even more deeply imbued with India’s culture, most notably William Jones (who founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta to deepen England’s awareness of the depths of this legacy). Cornwallis, smarting from his defeat in America, was determined to preclude the emergence of a similar settler community in India, so he banned anyone with an Indian parent from becoming a military or civilian officer of the Company.

By 1805, with the advent of Lord Wellesley, a further change began to appear, with the British becoming increasingly aloof from the locals, and more stubborn in the enforcement of their supremacy over all things Indian. By the 1820s, James Mill (who, like I said earlier, had never visited India) began asserting that there was absolutely nothing of value in India’s history, cultural heritage, or literature, and this was taken to new extremes by Thomas Macaulay, the overtly racist imperial bureaucrat who asserted ludicrously that ‘a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole literature of India and Arabia3.

The intellectually precocious Macaulay’s supposedly insatiable appetite for knowledge did not extend to the literature or heritage of the country he was being sent to administer. On the ship to India in 1834 (to become the Law Member in the Governor General’s Executive Council), this great bibliophile read books in Greek, Latin, English, French, Italian, and Spanish, ranging from the Iliad through Horace, Virgil, Dante, Gibbon, and Voltaire. But he did not bother to read anything about India apart from James Mill’s pernicious History of British India. The Hindustani and Farsi grammar texts he carried lay untouched.

Mill and Macaulay’s disdain for India’s past became the prevailing ideology of the British Empire after 1835 (and is still held unashamedly by the likes of historians Niall Ferguson and Robert Tombs). A small phalanx of urban Indians adopted these attitudes towards their past as well, epitomized by the talented Bengali poet, Madhusudan Dutt, who converted to Christianity, took the name Michael, and married an Englishwoman. Michael initially wrote poetry only in English, but eventually came to regret his disdain for India, and wrote a brilliant, inverted version of the Ramayana in Bengali, Meghnadbadh Kabya (The Saga of Meghnad’s Killing), in which Ravana is a heroic figure (and his son, Indrajit or Meghnad, is the central figure).

Mill and Macaulay’s disdain for India’s past became the prevailing ideology of the British Empire after 1835 (and is still held unashamedly by the likes of historians Niall Ferguson and Robert Tombs). A small phalanx of urban Indians adopted these attitudes towards their past as well, epitomized by the talented Bengali poet, Madhusudan Dutt, who converted to Christianity, took the name Michael, and married an Englishwoman. Michael initially wrote poetry only in English, but eventually came to regret his disdain for India, and wrote a brilliant, inverted version of the Ramayana in Bengali, Meghnadbadh Kabya (The Saga of Meghnad’s Killing), in which Ravana is a heroic figure (and his son, Indrajit or Meghnad, is the central figure).

Macaulay’s ‘Minute on Education’ sought to create ‘a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect’.4 There is little doubt that Macaulay succeeded amongst an elite veneer in urban India. But a subversive element remained, biding its time and chafing at the insults that were being thrown at the ancient culture of India. The growing racism of the British rulers—in stark contrast to their respectful initial attitudes to India’s cultures, languages, and religions—created a critical mass of opposition that burst forth in 1857–1858.

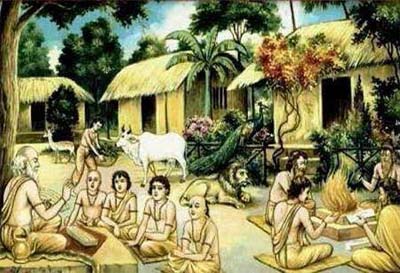

Although barely articulated at the time, the British revenue system had also systematically destroyed India’s extremely widespread community-based education system that ensured higher literacy rates in India than in Britain in the eighteenth (and early nineteenth) century. Painstaking research by Dharmapal, based primarily on a report commissioned by Thomas Munro (the governor of Madras Presidency) in each of the twenty-one districts of Madras between 1822 and 1826 (and other data from Bihar and Bengal), showed that,

… in terms of the content and proportion of those attending institutional school education, the situation of India in 1800 is certainly not inferior to what obtained in England then; and in many respects Indian schooling seems to have been much more extensive … The content of studies was better than what was studied in England. The duration of study was more prolonged. The method of school teaching was superior and it is this very method which is said to have greatly helped the introduction of popular education in England ….5

Munro himself was astonished that ‘every village had a school’; these traditional institutions (pathshalas, gurukuls, and madrasahs) were ‘kept alive by revenue contributions by the community including illiterate peasants’,6 and all villagers were committed to educating children. Dharmapal’s study showed that students started school between the ages of five and eight, and spent five to fifteen years being educated. The official reports had broken down the student body by caste (Brahmin, Vaishya, Shudra, ‘other castes’, and Muslims), and it was clear that the vast majority of students were from ‘groups termed Shoodra, and those considered below them who predominated in the thousands’.7 Teachers and students came from a variety of backgrounds, creating a richly diverse teaching environment. Until Dharmapal’s investigative book was published in 1983, the British and their successors had buried this information about a vibrant pre-colonial education system. What was clear was that the new colonial taxation system eroded the indigenous schools’ sources of local revenue support, and destroyed India’s community-based knowledge economy by 1850.

Modi’s India seeks to redress these imbalances that are a legacy of coloniality—a history of Hindus being naturally downtrodden during centuries of Muslim and Christian rule8. Constitutional lawyer J. Sai Deepak shows how colonialization is the software that provides the framework to mould the minds of a colonized people. Coloniality achieves fruition when a colonized (and even more, post-colonial) people are subconsciously colonialized—instinctively imbibing the attitudes of the colonizer, particularly towards their indigenous culture. Macaulay’s project was the epitome of coloniality.

Using legal avenues to build the new Ram temple at the lord’s birthplace in Ayodhya was part of the BJP’s conscious project of redressal, but its ultimate purpose was to rebuild the moral fibre of a long repressed civilization. Modi merely sought to make the majority faith the basis for the moral underpinning of the nation—as Catholicism is in France, Shinto-Buddhism in Japan, Protestantism in Britain (where the monarch solemnly swears to uphold it at his/her coronation), Judaism in Israel—while being faith-neutral in its delivery of social services. So, for instance, over 30 per cent of recipients of Prime Minister Modi’s housing subsidy (Awaas Yojana) programme are Muslims, as are 33 and 36 per cent of its farmer income support and microcredit schemes respectively9 (despite Muslims being less than 15 per cent of the overall population).

While redressing the most egregious iniquities the majority faith faced in the Nehruvian dispensation (including the persistence of a form of ‘jizya’—a tax uniquely imposed on Hindu temples but not on mosques or churches, as happened again in 2024 with Karnataka’s Congress government),10 the BJP seeks to unite India’s citizens. Ambedkar’s vision of the annihilation of caste is closer to the BJP’s approach than the Congress (under Rahul Gandhi) seeking to entrench caste rather than merit as the criterion for filling positions at the top of the bureaucracy and judiciary.

Coloniality is deeply embedded in the English-educated elite’s thinking (disdainful of non-speakers of English), as well as in India’s social structure—with the ‘Macaulayputra’ elite having slipped seamlessly into the supercilious status previously occupied by the British. Modi sought to remove the barriers between ‘brown sahibs’ and the broad mass, making significant headway among the mass, but meeting persistent resistance from the elites. At inaugurations of monuments, Modi has gone out of his way to dine with the workers, or touch the feet of those supposedly at the bottom of the social pyramid; he abolished the ‘red light culture’ in New Delhi (although it was still evident in some capitals of states ruled by other parties).

Those the elites called ‘the great unwashed’, increasingly wore clean clothes that made them less distinguishable from the elite, and were better fed (with free foodgrain, near-universal access to cooking gas, toilets, bank accounts, subsidies directly transferred to them—all helping to democratize economic opportunity). Those that would, thirty-five years earlier, have travelled by bullock cart, now do so on two-wheelers (an unobtrusive but clear symbol of progress, and faster mobility). The English language (still the exclusive language in high courts and the Supreme Court) remains a barrier between the elite and the mass, a continuing source of unequal access to justice, with 90 per cent of India’s people having first to jump the language hurdle before being able to access the higher judiciary, while lower courts remained mired in corruption and long delays.11 Judicial reform remains part of Modi’s unfinished agenda.

Decluttering Macaulayputra minds may require a few more decades, but de-coloniality is increasingly embedded in the new generations educated in the post-2001 era of universal, compulsory education until age 14. Coloniality won’t be abolished overnight, but its cleansing is well on its way.

1 Will Durant, The Case for India, Strand Book Stall, Mumbai 2007. (First published in 1931), p. 3.

2 Ibid., p. 4.

3 Zareer Masani, Macaulay: Pioneer of India’s Modernization, New Delhi: Random House India, 2012,

p. 90.

4 Ibid., p. 101.

5 Dharmapal, The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century. Goa: Other India Press, 1983, p. 20.

6 Ibid., p. 21.

7 Ibid., p. 23.

8 See J. Sai Deepak, India, That Is Bharat: Coloniality, Civilisation, Constitution. New Delhi: Bloomsbury India, 2021.

9 Anand Ranganathan, Hindus in Hindu Rashtra. Noida: BlueOne Ink, 2023, p. xvii. The formal names of the other two schemes are Kisaan Sammaan Nidhi Yojana and the MUDRA Yojana.

10 ‘Karnataka Govt Plans to Table Temple Tax Bill again’, News18, 29 February 2024.

11 India is not unique in using the language of a former conqueror in its courts. For over three centuries after the Norman invasion of England in 1066, French was the language of England’s courts. It was only after English replaced French in the early fifteenth century that England began achieving economic success. Similarly, Persian (Farsi) was the language of India’s courts until the 1830s, and English persists seventy-seven years after Independence.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Prasenjit K. Basu’s ‘Asia Reborn’ won the Best First Book award at the Tata Literature Live! Mumbai LitFest, 2018. His new book, ‘India Reborn’ has just been published. PK was Chief Economist (SE Asia & India) at Credit Suisse First Boston and Chief Asia Economist at Daiwa Securities for 5 years each. Among other roles, he was Chief Economist at ICICI Securities and Malaysia’s Khazanah Nasional, CEO of Maybank Kim Eng Research Pte Ltd, board member of Tata Capital Pte Ltd, and Macquarie Malaysia, and Director of the Asia Service at Wharton Econometrics in Philadelphia, and Director of Asian Macroeconomics at UBS Securities. He has dual Master’s degrees in Public Administration and International Relations from the University of Pennsylvania, and completed PhD coursework in International Political Economy there.

Prasenjit K. Basu’s ‘Asia Reborn’ won the Best First Book award at the Tata Literature Live! Mumbai LitFest, 2018. His new book, ‘India Reborn’ has just been published. PK was Chief Economist (SE Asia & India) at Credit Suisse First Boston and Chief Asia Economist at Daiwa Securities for 5 years each. Among other roles, he was Chief Economist at ICICI Securities and Malaysia’s Khazanah Nasional, CEO of Maybank Kim Eng Research Pte Ltd, board member of Tata Capital Pte Ltd, and Macquarie Malaysia, and Director of the Asia Service at Wharton Econometrics in Philadelphia, and Director of Asian Macroeconomics at UBS Securities. He has dual Master’s degrees in Public Administration and International Relations from the University of Pennsylvania, and completed PhD coursework in International Political Economy there.