India’s Strategic Infrastructure Deterrence

China’s strategy along India’s eastern frontier rests on speed, intimidation, and the exploitation of geography. That advantage is now eroding. The Brahmaputra tunnel and the Dibrugarh Emergency Landing Facility together negate Beijing’s long-held assumption that the Northeast can be isolated through terrain, weather, or engineered coercion. What China built through roads, dams, and forward villages to compress India’s response time has been structurally countered by Indian infrastructure that restores depth, redundancy, and tempo.

This is not symbolic deterrence. It is an operational denial. Rapid mobilisation, sustained air power, and uninterrupted logistics convert the eastern theatre from a vulnerability into a zone of resilience. Weaponised flooding, salami slicing, and Chumbi-based pressure lose strategic effect when mobility is continuous, and response is immediate.

The message to China is unambiguous: incrementalism will no longer yield advantage. Geography can no longer be bent against India. The eastern rampart now imposes costs, shortens warning cycles, and removes surprise. Deterrence has shifted from intent to capability.

The Brahmaputra Underwater Tunnel: A Game Changer

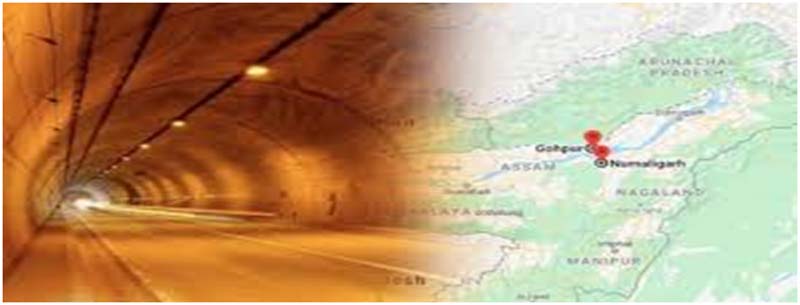

The inauguration of the Brahmaputra underwater tunnel on 14 February 2026 is a milestone in the eastern Indian strategy. The tunnel, stretching 33.7 kilometres, is built as a twin-tube tunnel under the river, connecting Gohpur on the north bank to Numaligarh on the south bank in the vicinity of Dibrugarh. Located almost 32 metres beneath the riverbed, it compresses what used to be a 240km diversion into a straight 34km tunnel. The distance that took more than six hours before is now covered within half an hour. All concealed, silent but disruptive to the adversary.

This is not merely an exercise in connectivity or regional development. The tunnel represents a decisive shift in India’s eastern defence posture at a time when Chinese military infrastructure and operational patterns increasingly threaten the Siliguri Corridor, the narrow land bridge linking mainland India to the Northeast. Barely 22 kilometres wide at its most vulnerable stretch, Siliguri remains the most consequential geographic choke point in the Indian Union. From the Chumbi Valley in Tibet, located roughly 130 kilometres away, the People’s Liberation Army retains the theoretical ability to disrupt this corridor in the opening hours of a high-intensity contingency. Added is the dimension of the Teesta River Comprehensive Management and Restoration Project in Bangladesh being given to China, which has caused significant security concerns for India due to its proximity to the strategic Siliguri Corridor.

China’s approach to the eastern sector has been deliberate and cumulative. Border villages constructed as civilian settlements double as logistics nodes. The airfields, feeder roads and rail spurs leading to Arunachal Pradesh have continued to proliferate, and are reinforcing the long-held position of Beijing in what it claims as South Tibet. The pace of forward deployments and reserve mobilisations has been on the rise since the Galwan crisis of 2020, followed by the confrontations in Tawang in Dec 2022. Field exercises of considerable length, and stocking cycles in winter conditions indicate training not to episodic signalling, but as a tool of cognitive coercion.

This trend was also evident in the past when the Chinese troops tried to change the status of the ground at Siliguri-based commanding heights and at Doklam in 2017. The objective was strategic leverage: compel India to accept incremental loss or risk strategic dislocation of its Northeast. The lesson was unambiguous. The lesson was unambiguous. Geography could no longer be trusted to provide a deterrent on its own, and these had to be supplemented by speed, redundancy and depth. However, the Indian Army stood its ground and thwarted the Chinese most professionally.

Even the Brahmaputra has entered this competition. It is controlled by large upstream dams in Tibet, such as the Medog project, that govern seasonal flows that play an important role in the Assam agrarian economy and population. On top of this, civilian infrastructure coming up, such as modern villages and settlements provide latent military utility. Covert troop movement and staging logistics in wartime could access through these corridors, an element of technical deception in China. The hydropower resources and infrastructure development, therefore, become a force-projection means, just as the G219 highway in facilitating armoured mobilisation into Ladakh in quick time.

The Brahmaputra tunnel is representative of a countering of Chinese designs and engineering as a strategy. At an estimated cost of Rs 20,000 crore and incorporating rail connectivity at the Prime Minister’s insistence, the tunnel eliminates monsoon-induced paralysis that once plagued military movement across the river. Ferry dependence routinely delayed formations by days. That vulnerability has now been structurally removed.

The Mountain Strike Corps can move to locations in Arunachal in less than 24 hours, which is a significant reduction compared to earlier capabilities. The tunnel, when combined with the Bogibeel Bridge and other developing logistics bases of Dhubri and Kishanganj, will add to a stratified defence of the Siliguri axis against attacks on the Chumbi salient. Robust portal, reinforced linings and in-built surveillance systems make them more survivable in case of any impending threat.

Dibrugarh Emergency Landing Facility as a Force Multiplier.

The strategic value of the tunnel is magnified through its integration with the Dibrugarh Emergency Landing Facility. Operational since 2023 under the Indian Air Force’s dual-use airfield programme, this 3-kilometre runway supports both civil aviation and frontline combat operations. Being an ELF, it is fully equipped for Su-30MKI and Rafales, backed with secured shelters, fuel storage and quick repair facilities.

The ELF is located some 450 kilometres north of Tawang and 300 kilometres from Siliguri, and addresses a long-term gap in air cover in the Upper Assam region. In the past, Chinese planes based at high altitude, like Bangda, had the benefit of sorties based on range and altitude. It is now offset that asymmetry.

The delivery of ammunition, spares and fuel in Numaligarh depots to the ELF complex can be transported in a quick time. Precision munitions, heavy calibre ammunition and air defence equipment are all refuelable without being subjected to surface interdiction. The modern strike aircraft detachments based at Chabua and Dibrugarh maintain continuous patrols and regular aerial patrols using the runway.

Integrated air defence also increases the battlespace. The Akash NG and Akashteer systems moved by tunnels create overlapping coverage of the Chumbi approaches and are linked with the S-400 missiles in depth, covering the area in a multi-tiered, multi-layered Air Defence architecture. This package dominates the enemy airspace, diminishing the feasibility of reconnaissance operations and strike attacks against the eastern front.

Operational Scenarios and Strategic Effects

In a contingency centred on the Tawang sector, rapid PLA mobilisation from Medog coupled with diversionary manoeuvres toward Sela Pass would previously have strained Indian response timelines. Seasonal flooding compounded delays, fragmenting force cohesion. Under the current configuration, mechanised elements, armour and artillery reach operational zones within hours. Air operations from Dibrugarh generate sustained sorties, while mobile missile units threaten logistics nodes across the Tibetan plateau.

Hybrid contingencies, including the activation of insurgent networks along the Myanmar border with external support, are similarly mitigated. Tunnel-enabled mobility allows paramilitary and army units to saturate vulnerable corridors rapidly. Persistent ISR from ELF-based platforms ensures early detection and precision response.

Even coercive use of water as a weapon loses potency. Sudden releases from upstream dams, intended to isolate northern bank formations, no longer sever logistics. Continuity of movement is preserved, and retaliatory options against critical infrastructure remain credible.

In a dual-front scenario, with western forces engaged elsewhere, the tunnel-ELF complex sustains eastern combat power autonomously. Airlifted formations, missile deployments and rapid rail movement deny adversaries the opportunity to exploit geographic or temporal gaps.

Doctrinal and Geostrategic Implications

Together, the Brahmaputra tunnel and the Dibrugarh ELF institutionalise a doctrine of accelerated mobilisation and credible deterrence tailored to eastern terrain. Response cycles shrink from days to hours. Theatre-level coordination improves as logistics, air power and ground manoeuvre converge on hardened nodes rather than vulnerable river crossings.

Beyond the military domain, the infrastructure reinforces economic and energy security. Reliable integration of Northeast hydropower into the national grid underwrites regional development and strategic sustainability. Indigenous expertise gained in subaqueous construction carries implications for future projects in island territories and friendly regional countries.

Chinese reactions underscore the shift. Adjustments within the Eastern Theatre Command followed the tunnel’s clearance, reflecting recognition that India has neutralised a long-perceived vulnerability. The eastern rampart is no longer defined by fragility, but by depth and resilience.

Conclusion

The Brahmaputra tunnel, along with the Dibrugarh Emergency Landing Facility, makes geography an asset, rather than a liability. It strengthens the eastern borders of India not symbolically, but structurally. Arunachal Pradesh is not a periphery anymore; it is a part of the integrated battle space. The Achilles heel of Indian strategy has been the Siliguri Corridor, which now lies within the depth of mobility and time-critical precision firepower.

Designed based on the lessons at Doklam and Galwan, this architecture is an indicator that the next battles in the eastern Himalayas are going to be determined by the possibility of India to move more quickly, stay longer and retaliate more profoundly. In such calculus, it is the asymmetry that has flipped.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.