Behind the scenes of a centennial retrospective with curator Kishore Singh

What is a dream project? Something you want to do or achieve – an occasion you create within the realm of achievable aspirations. But there are others that lie outside that ken, something so unfeasible, you never, ever consider them. Till, well, destiny chooses otherwise. So, when Feroze and Mohit Gujral reached out to me to curate the centennial retrospective on Satish Gujral, it was an opportunity out of the blue, something I willingly dropped other projects to work on. A centennial exhibition is a big thing, but one on Gujral sa’ab – and at the National Gallery of Modern Art, at that – was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Of course, I said yes.

I had known Gujral sa’ab over many decades, first as a journalist and editor, and more lately as part of the art world involved in research and scholarship rather than commerce. Out meetings were never frequent, but they were always warm with affection, raconteurship and hospitality. At his home designed by Raj Rewal, those meetings – with his wife Kiran Gujral interpreting for him – opened up discussions around his practice. Other artists represented the great diversity of their talent through their choice of subject and material, but Satish Gujral was encyclopaedic in himself: painter, sculptor, muralist, architect, each of which he spoke about with great passion. More even than that, he was the quintessential Delhi artist, its primus inter pares – the first among equals who made a habit of attending the openings of other artists, while, at home, the Gujral parties were as legendary as their guests.

In the melee of success and celebration, it was easy to overlook Gujral sa’ab’s impairment. He had been clinically deaf since the age of eight, following a swimming accident in Undivided India’s Punjab. Perhaps the die was cast then, for the 1930s offered few recourses to a boy with no hearing. Gujral learned to speak languages phonetically with the help of his brother Inder (later, Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral); gained his art pedagogy from the Mayo School of Arts in Lahore and the J.J. School of Art in Bombay; won a scholarship to Mexico; created a series of heart wrenching paintings on the Partition and emerged as its greatest visual chronicler; went on to pioneer abstraction; represented the aftermath of the Emergency and the Delhi riots of 1984 using burnt wood and leather (to represent the citizenry that had been incinerated alive); made extraordinary metal reliefs in a refreshing new language; before creating iconic private and institutional buildings (New Delhi’s Belgian Embassy and Panjim’s Goa University among them) as a self-taught architect that won accolades and awards around the world. How was one to compress all of this “genius” – art critic Charles Fabri’s term to describe Gujral sa’ab’s work – into one exhibition?

In the melee of success and celebration, it was easy to overlook Gujral sa’ab’s impairment. He had been clinically deaf since the age of eight, following a swimming accident in Undivided India’s Punjab. Perhaps the die was cast then, for the 1930s offered few recourses to a boy with no hearing. Gujral learned to speak languages phonetically with the help of his brother Inder (later, Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral); gained his art pedagogy from the Mayo School of Arts in Lahore and the J.J. School of Art in Bombay; won a scholarship to Mexico; created a series of heart wrenching paintings on the Partition and emerged as its greatest visual chronicler; went on to pioneer abstraction; represented the aftermath of the Emergency and the Delhi riots of 1984 using burnt wood and leather (to represent the citizenry that had been incinerated alive); made extraordinary metal reliefs in a refreshing new language; before creating iconic private and institutional buildings (New Delhi’s Belgian Embassy and Panjim’s Goa University among them) as a self-taught architect that won accolades and awards around the world. How was one to compress all of this “genius” – art critic Charles Fabri’s term to describe Gujral sa’ab’s work – into one exhibition?

The Gujral Foundation, co-founded by Feroze and Mohit Gujral, had already been working on the project when I joined the team. But there was still ambiguity about how to shape it. Eventually, it was agreed that the NGMA exhibition would take into consideration only his art practice, while his architectural decades would be represented by a separate exhibition at The Gujral House, now converted by the Foundation into a museum that may eventually house part of its permanent collection as well as host related exhibitions and events. What united us was one vision: that through these exhibitions, Satish Gujral had to receive his due as one of the great masters of the twentieth century.

The Gujral Foundation, co-founded by Feroze and Mohit Gujral, had already been working on the project when I joined the team. But there was still ambiguity about how to shape it. Eventually, it was agreed that the NGMA exhibition would take into consideration only his art practice, while his architectural decades would be represented by a separate exhibition at The Gujral House, now converted by the Foundation into a museum that may eventually house part of its permanent collection as well as host related exhibitions and events. What united us was one vision: that through these exhibitions, Satish Gujral had to receive his due as one of the great masters of the twentieth century.

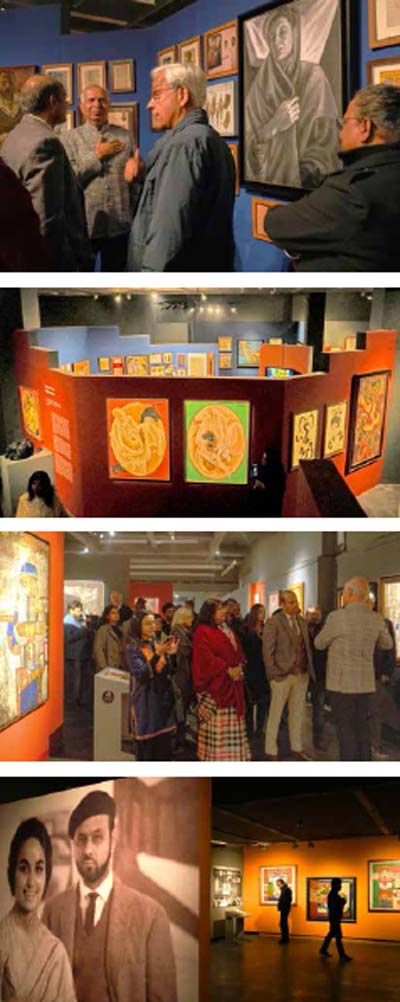

Feroze spearheaded the project. An inveterate note-taker, she was its lively force that helped shape the vision over endless coffees and some lunches; Mohit helped with ideas, suggestions, and when stuck in a messy spot, with his “executive decisions”. The Foundation’s engaging and lively team added those who would shape it further – scenographer Aashwin Bhargava who virtually built a Satish Gujral City within NGMA’s cavernous exhibition hall; filmmaker Pryas Gupta as technology consultant; ; lighting expert Rahul Singh to ensure eliminate ambient light in favour only of lighted artworks; and, naturally, a production team to make it all happen.

An exhibition on this scale is a mammoth task, and at least as complicated. The cliché, “Change is the only constant”, was only too true as the planning moved ahead. The works belonging to Feroze and Mohit, many in storage, needed to be taken out and checked for condition and framing; but it left many important gaps for which loans had to be requested – from the National Gallery of Modern Art, the Chandigarh Museum and Art Gallery and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art – all of which have considerable collections of Gujral’s works; others that belonged to family members and friends; and requests, too, from important collectors. Based on feedback and availability, the likely displays, sizes of walls and sections kept changing to accommodate not just their quality but their individual scale as well. Pedestals had to be built, wall colours decided, wallpapers created for atmosphere, wall texts mapping his journey and the artistic contexts planned, videos and interviews selected and, for me personally, a selection of memorabilia around his life collated for a planned studio that turned into a memorial room with his paintbrushes, palettes, cleaning rags, unfinished paintings, certificates, awards, letters and diary writings, and photographs. Inevitably, till the formal opening of the exhibition, work was underway – the final displays, artwork captions, lighting adjustments, cleaning…

Gujral sa’ab’s contribution to the world of Indian art is unmeasurable, not just through his immense and iconic legacy but also because of the manner he shaped the following generation within the family. Daughters Alpana and Raseel went on to create successful careers in design; son Mohit – and many may not know this – trained as an architect to support his own architectural journey in the face of immense opposition from architects in the country and went on to run a successful architectural design firm and retired as CEO of DLF; while daughter-in-law Feroze was dispatched to artists’ and designers’ studios, when young, thereby nurturing the instinct that has shaped many of the Foundation’s activities.

Gujral sa’ab’s contribution to the world of Indian art is unmeasurable, not just through his immense and iconic legacy but also because of the manner he shaped the following generation within the family. Daughters Alpana and Raseel went on to create successful careers in design; son Mohit – and many may not know this – trained as an architect to support his own architectural journey in the face of immense opposition from architects in the country and went on to run a successful architectural design firm and retired as CEO of DLF; while daughter-in-law Feroze was dispatched to artists’ and designers’ studios, when young, thereby nurturing the instinct that has shaped many of the Foundation’s activities.

For me, it was the discoveries that were most exciting. Familiar with most phases of his work, it was a revelation that he had also worked with fabric and thermocol to create works of art; or that he had designed several incredible pavilions for Asia 72, pioneering a concept of muralism in the country, examples of which one can see while driving around Lutyens’s building facades: Delhi High Court, Shastri Bhawan, Baroda House…among others. One such mural at The Oberoi was, alas, removed during an earlier renovation phase, making it imperative that his as well as everyone else’s artistic commissions are preserved for future generations.

The exhibition opened last month and will run till the end of March at NGMA; the architecture exhibition will be on simultaneously at Gujral House, but other projects are also part of the centennial exhibition: the artist’s biography, A Brush With Life, was re-issued by Harper Collins at JLF Jaipur in January; my own large monograph on the artist gets released this month at NGMA’s Night at the Museum as an India Art Fair collateral event. His presence will be marked at the art fair too, as also at CEPT University, Ahmedabad, where the Foundation supports students, in Chandigarh and Jalandhar, where it works closely…a fitting tribute to the legacy of an artist whose journey is closely intertwined with that of the nation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kishore Singh is an independent art writer and curator. His recent projects include a book and Satish Gujral retrospective at NGMA (till 30 March) and The Portrait of an Artist (published by Mapin).

Kishore Singh is an independent art writer and curator. His recent projects include a book and Satish Gujral retrospective at NGMA (till 30 March) and The Portrait of an Artist (published by Mapin).