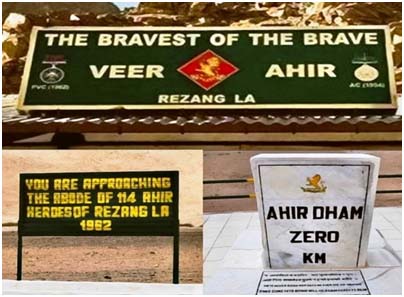

Rezang La

At 18,000 feet in Ladakh’s frozen wilderness, where the air itself feels like an enemy and the wind cuts like a blade, a handful of Indian soldiers carved their names into legend. This was Rezang La, November 1962—a battle as fierce as Thermopylae or Saragarhi, yet fought in harshest conditions.

The ridge was desolate: minus 30 to minus 40 degrees Celsius, no cover, no vegetation, only stone and silence. Into this silence marched C Company, 13 Kumaon, composed largely of Ahir (Yadav) soldiers from Haryana’s plains. Farmers turned fighters, they were tasked with an impossible order: Hold Rezang La. Their commander, Major Shaitan Singh Bhati, was a man of quiet steel. His mission was clear—guard the approaches to Chushul, the gateway to Ladakh. If Rezang La fell, the valley would open to the enemy.

The company’s positions were exposed: shallow trenches and stone sangars, with little artillery support. Against them stood the might of the Chinese army, determined to break India’s defences. On 18 November 1962, the storm arrived. Before dawn, the ridge shook under a relentless bombardment. Mortars and artillery thundered, communication lines snapped, and the sky flashed with fire. Out of the smoke came wave after wave of Chinese soldiers—hundreds at a time, advancing from multiple directions. Their plan was simple: overwhelm by sheer numbers.

But the men of C Company answered with fury. Rifles cracked, light machine guns rattled, and each shot echoed like defiance in the thin air. The Ahirs fought with cold precision, cutting down ranks of attackers. The slopes became littered with bodies, yet fresh waves surged forward. In the midst of chaos, Major Shaitan Singh moved from post to post under fire, correcting fields of fire, encouraging his men. His presence was a beacon: “We hold together. We die together if we must.” Even when bullets tore into him, he refused evacuation, continuing to lead from behind a boulder, bleeding but unyielding.

The cold gnawed at flesh, metal froze to skin, and ammunition dwindled. Yet the defenders fought on. When bullets ran out, bayonets were fixed. When bayonets broke, they fought hand-to-hand—rifle butts, stones, bare fists against the tide. One by one, posts were overwhelmed, not by retreat but by annihilation. When silence finally returned to Rezang La, the ridge was strewn with heroes. Weeks later, recovery parties found a haunting sight: bodies still in firing positions, weapons in hand, facing the enemy. Around machine guns lay men in semi-circles, showing they had fought until the last round. Of about 120 soldiers, 114 had fallen. They had not yielded an inch.

Even the enemy was shaken. An outnumbered company had turned a barren ridge into a fortress of fire and resolve. For his unmatched courage and sacrifice, Major Shaitan Singh was awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India’s highest gallantry honour. Rezang La was not just a battle. It was a crucible of spirit, fought against impossible odds of terrain, weather, and numbers. On that frozen ridge, C Company, 13 Kumaon, under Major Shaitan Singh, wrote a chapter of courage so absolute that it stands among the world’s greatest Last Stands. Rezang La was a wall of men against a tide of steel. And the men did not fail.

Even the enemy was shaken. An outnumbered company had turned a barren ridge into a fortress of fire and resolve. For his unmatched courage and sacrifice, Major Shaitan Singh was awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India’s highest gallantry honour. Rezang La was not just a battle. It was a crucible of spirit, fought against impossible odds of terrain, weather, and numbers. On that frozen ridge, C Company, 13 Kumaon, under Major Shaitan Singh, wrote a chapter of courage so absolute that it stands among the world’s greatest Last Stands. Rezang La was a wall of men against a tide of steel. And the men did not fail.

Widow vs the State

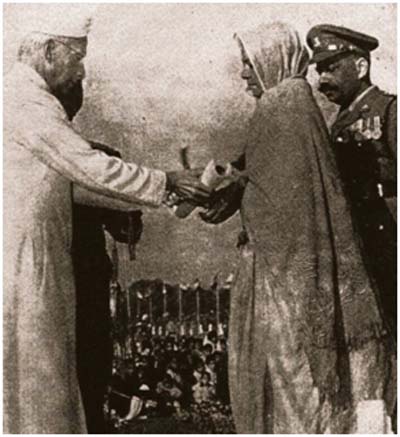

When the guns at Rezang La fell silent in November 1962, the echoes of sacrifice reached a quiet home far away. There, Smt Sugan Kunwari—wife of Major Shaitan Singh, Param Vir Chakra awardee—was thrust into a battle of her own. Overnight, she became a widow, a mother, and the custodian of a hero’s memory. The nation hailed her husband as immortal. Leaders spoke of sacrifice, garlands adorned memorials, and medals were pinned. But once the ceremonies ended, silence descended. What remained was a young widow, a few photographs, and the hope that the country her husband died for would at least honour its promises.

When the guns at Rezang La fell silent in November 1962, the echoes of sacrifice reached a quiet home far away. There, Smt Sugan Kunwari—wife of Major Shaitan Singh, Param Vir Chakra awardee—was thrust into a battle of her own. Overnight, she became a widow, a mother, and the custodian of a hero’s memory. The nation hailed her husband as immortal. Leaders spoke of sacrifice, garlands adorned memorials, and medals were pinned. But once the ceremonies ended, silence descended. What remained was a young widow, a few photographs, and the hope that the country her husband died for would at least honour its promises.

By law, as the widow of a battle casualty and PVC recipient, she was entitled to a Liberalised Special Family Pension (LSFP)—equal to 100% of his last pay. This was not charity; it was her right. Yet, through bureaucratic indifference, she was placed on a normal family pension, barely 30% of his salary. The difference was devastating. It meant deferred school fees, leaking roofs unrepaired, and children growing up with less than what was owed to them. The nation called her husband a treasure; the system treated his widow as a clerical oversight.

In 1963, she received a gratuity of ₹4,000—a small but meaningful support. But in 1964, the same system clawed it back, deducting the amount from her pension as “excess.” For a war widow, this was not an accounting correction; it was betrayal. No apology came, only cold deductions. In 1972, pension rules were liberalised. On paper, widows of battle casualties were promised better scales and additional gratuity. For Sugan Kunwari, it should have been transformative. Instead, from 1972 to 1995, she continued to receive the reduced pension. The promised ₹9,500 gratuity never reached her. Twenty-three years passed—her children grew, struggled, and matured—while she lived on less than what the law guaranteed. Her husband’s gallantry was celebrated; her rightful dues remained trapped in files.

In 1963, she received a gratuity of ₹4,000—a small but meaningful support. But in 1964, the same system clawed it back, deducting the amount from her pension as “excess.” For a war widow, this was not an accounting correction; it was betrayal. No apology came, only cold deductions. In 1972, pension rules were liberalised. On paper, widows of battle casualties were promised better scales and additional gratuity. For Sugan Kunwari, it should have been transformative. Instead, from 1972 to 1995, she continued to receive the reduced pension. The promised ₹9,500 gratuity never reached her. Twenty-three years passed—her children grew, struggled, and matured—while she lived on less than what the law guaranteed. Her husband’s gallantry was celebrated; her rightful dues remained trapped in files.

Only in 1996, more than three decades after Rezang La, did the State finally admit she was entitled to LSFP. Her pension was corrected going forward, but the past was erased. No arrears for 1972–1995, no gratuity, no compensation for decades of deprivation. The message was clear: justice delayed is justice denied. Refusing to surrender, she and her son Narpat Singh took the fight to the Armed Forces Tribunal, Jaipur. Their demand was simple: arrears, gratuity, and recognition. Yet hearings dragged, judges were absent, files shuffled endlessly. Delay became the weapon of the system. Her husband’s last stand lasted hours. Hers stretched into decades.

By 2015, she had grown old, her face etched with battles fought in silence. The case was still pending. She died without seeing arrears, gratuity, or closure. Her husband fell to enemy fire; she fell to bureaucratic apathy. Both were warriors—one against guns, the other against files. After her death, Narpat Singh continued the fight, not for money but for honour. Even by Jan 2026, the case remained unresolved. Six decades after Rezang La, the family still waits. India recognised bravery in months. It has yet to recognise justice in sixty years.

Two Warriors, One Nation’s Conscience

On a frozen ridge in 1962, Major Shaitan Singh and his men of C Company chose death over dishonour. At Rezang La, they fought until the last bullet, the last breath, proving that courage can outlive flesh. Their stand became immortal. Far from the gun smoke and snow, another battle began. His widow, Smt. Sugan Kunwari, was left to fight not enemies across the border, but the cold indifference of her own country. Her war was longer, lonelier, and just as merciless.

Between Rezang La and the corridors of bureaucracy lies a brutal contrast:

- At Rezang La, India proved it can produce courage beyond imagination.

- In Sugan Kunwari’s lifetime, India proved it can produce indifference beyond justification.

If the widow of a Param Vir Chakra hero must fight for decades, what hope remains for ordinary soldiers’ families? Rezang La must remain our symbol of bravery. Sugan Kunwari’s struggle must become our symbol of justice. Only then will we be worthy of those who stood, fought, and fell—on the ridge, and in silence at home. Kautilya, in Arthashastra, insisted on prompt, regular payment to soldiers and, importantly, caring for their families, wives and children, while they were away on duty, ensuring their peace of mind. He warned his king, Chandragupta Maurya that the day a soldier/his family has to demand or plead for its dues, the ruler loses the moral authority to govern and the kingdom risks collapse. Timely payment of the armed forces is a sacred duty of the state.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LLt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, a former DGBR, is a writer and social observer. He also pursues his passion for the creative arts in his free time.

LLt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, a former DGBR, is a writer and social observer. He also pursues his passion for the creative arts in his free time.