Introduction

In contemporary security discourse, infrastructure is no longer viewed merely as an enabler of economic growth. Increasingly, it is recognised as a critical instrument of national power, shaping military capability, deterrence posture, and strategic autonomy. Nowhere is this more evident than in regions characterised by contested borders, difficult terrain, and unresolved geopolitical fault lines.

For India, strategic infrastructure along the Northern borders—particularly in relation to China—has assumed decisive importance. Roads, tunnels, bridges, rail links, logistics nodes, and airfield connectivity in high-altitude and remote areas directly influence the Indian Army’s ability to mobilise, sustain, and manoeuvre forces. In such environments, infrastructure asymmetry can translate rapidly into operational disadvantage.

While India has made notable strides in recent years, the challenge ahead is not incremental improvement but structural acceleration. This necessitates a re-examination of existing delivery models for strategic infrastructure and an exploration of alternative mechanisms that can combine speed, scale, and sustainability without compromising sovereign control.

Understanding Strategic Infrastructure

Strategic infrastructure refers to assets whose primary purpose is to serve national security objectives rather than commercial or civilian demand. These assets typically include:

- Border and approach roads in forward areas.

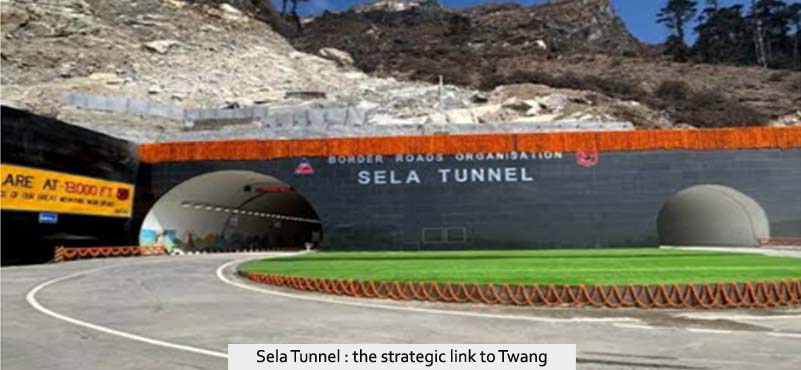

- All-weather tunnels and bridges in high-altitude terrain.

- Connectivity to advanced landing grounds and military installations.

- Strategic rail corridors in sensitive regions.

- Logistics hubs, fuel depots, and storage facilities.

- Dual-use infrastructure with predominant military utility.

The value of such infrastructure cannot be captured through conventional financial metrics. Its returns are measured instead in reduced mobilisation time, improved logistics reliability, enhanced deterrence, and operational resilience.

Unlike commercial infrastructure, strategic projects are often characterised by:

- Negligible or non-existent user revenue.

- Severe climatic and geological challenges.

- Limited construction windows.

- High uncertainty and risk.

- Restricted civilian access.

These features fundamentally shape the choice of delivery and financing models.

India’s Strategic Infrastructure Imperative

India’s Northern borders present a uniquely demanding infrastructure environment. High altitude, fragile ecology, extreme weather conditions, and sparse population densities combine to raise construction costs and execution risks. At the same time, the operational requirement for year-round connectivity and rapid force deployment has intensified.

Over the past decade, agencies such as the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), NHIDCL, and the Indian Railways have expanded their footprint in these regions. Budgetary allocations have increased, and execution capacity has improved. However, the scale of infrastructure required over the next decade runs into several lakh crore rupees, far exceeding what can be sustainably accommodated through annual budgetary allocations alone.

Moreover, infrastructure development along the northern borders is not merely a domestic concern. China’s extensive investment in transport and logistics infrastructure across the Tibetan plateau has altered the strategic balance by enabling rapid mobilisation and sustained force presence. This creates an imperative for India to narrow the infrastructure gap within compressed timelines.

The Dominance of the EPC Model

With creation of NHIDCL in July 2014 and enabling BRO to execute projects through Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) in August 2017, India has relied almost exclusively on EPC model for strategic infrastructure. This approach offers several advantages:

- Full government ownership and control.

- Clear accountability.

- Minimal private sector exposure to sensitive areas.

However, the EPC model also has inherent limitations:

- Project execution is constrained by annual budget availability.

- Cost overruns are borne entirely by the exchequer.

- Limited incentives for lifecycle optimisation and maintenance.

- Capacity constraints within public agencies.

While EPC remains indispensable for certain categories of strategic works, its exclusive use risks slowing the pace of infrastructure creation at a time when acceleration is strategically necessary.

Why Public–Private Partnership Has Been Avoided

Public–Private Partnership (PPP) has transformed sectors such as highways, airports, and power generation in India. Yet it has been conspicuously absent from strategic infrastructure. The reasons are well understood:

- Absence of tolling or user charges.

- High construction and operational risk.

- Security sensitivities.

- Long gestation periods and uncertain returns.

These concerns are legitimate. However, they have led to a binary policy approach: strategic infrastructure is equated with direct government execution, while PPP is associated solely with commercially viable projects. This binary framing overlooks the diversity of PPP models and, crucially, the role of Viability Gap Funding (VGF) as a risk-mitigation and fiscal-smoothing instrument.

Rethinking Viability Gap Funding

VGF was conceived precisely to address projects that are economically justified but commercially unviable. It recognises that certain public goods cannot be delivered solely through market mechanisms and require targeted state support. In India, VGF has been successfully deployed in:

- National highways.

- Airports and regional connectivity.

- Urban transport systems.

The key lesson from these sectors is that VGF is not a subsidy in the pejorative sense, but a tool for aligning public objectives with private execution capacity. Strategic infrastructure, by its very nature, represents the most compelling case for VGF. Its benefits accrue overwhelmingly to the state, and expecting commercial viability without public support is neither realistic nor necessary.

Learning from the Chinese Experience

China’s rapid development of border infrastructure is frequently cited in Indian strategic discourse. While institutional and political differences preclude direct replication, the underlying logic is instructive. China deploys large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) backed by assured financing from policy banks. These entities execute projects without regard to commercial returns, with losses absorbed by the state. Functionally, this system resembles PPP with near-total viability support. India lacks comparable infrastructure SOEs operating at such scale. Consequently, a VGF-backed PPP framework represents the closest functional equivalent within India’s democratic and fiscal architecture.

Setting the Conceptual Foundation

The core argument of this article is that strategic infrastructure requires a distinct PPP framework, one that differs fundamentally from commercial PPPs. Such a framework must:

- Eliminate reliance on user revenue.

- Allocate risk realistically.

- Preserve full sovereign control.

- Provide fiscal predictability.

- Incentivise execution speed and lifecycle performance.

VGF, when integrated with annuity-based PPP models, offers a credible pathway to achieve these objectives.

VGF: Concept and Rationale

VGF was introduced in India as a policy instrument to address a structural dilemma in infrastructure development: the divergence between economic necessity and commercial viability. Many infrastructure assets generate significant public value—through connectivity, regional integration, and security—but fail to generate sufficient private revenue to attract market-based investment.

VGF bridges this gap by providing targeted government support to projects that are socially and strategically justified but financially unviable on a stand-alone basis. Crucially, VGF is designed not as open-ended fiscal support, but as a calibrated mechanism to allocate risk efficiently and crowd in private participation. India’s experience with VGF over the past two decades offers valuable insights into both its potential and its limitations.

Highways: The Most Successful Application of VGF. The highways sector represents the most mature and successful application of VGF in India. Early PPP models based on toll revenues revealed significant weaknesses, particularly in traffic forecasting and demand risk allocation. This led to stalled projects, financial stress, and loss of investor confidence.

The policy response was the evolution towards annuity-based structures, most notably the Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM). Under HAM:

- The government contributes a portion of the project cost during construction.

- The private partner finances the balance.

- The government pays fixed annuities linked to asset availability.

- Traffic and revenue risk are fully retained by the state.

This model effectively transformed VGF from a one-time subsidy into a structured risk-sharing mechanism. The results were significant: revival of private participation, improved execution timelines, and enhanced asset quality due to long-term maintenance obligations. The highways experience demonstrates a critical principle that VGF succeeds when the government retains risks that the private sector cannot reasonably manage.

Airports and Urban Infrastructure: Conditional Success. VGF has also been deployed in airports and urban transport systems, albeit with mixed outcomes. In airports, particularly under regional connectivity initiatives, VGF compensated for low initial passenger volumes while enabling long-term growth.

Urban infrastructure—such as metro rail projects—relied heavily on government support, including VGF, state guarantees, and equity participation. While these projects achieved operational success, they highlighted governance challenges related to fare regulation, land acquisition, and inter-agency coordination.

The key takeaway is that VGF works best in environments where institutional arrangements are stable and decision-making authority is clearly defined.

Ports and Railways: Lessons from Failure. In contrast, early attempts to apply VGF in ports and railways were largely unsuccessful. In ports, demand projections proved overly optimistic, regulatory frameworks were rigid, and connectivity delays undermined throughput. In railways, private operators were expected to bear commercial risks without corresponding control over operations or pricing.

These failures underscore an important lesson that VGF cannot compensate for flawed institutional design or misaligned risk allocation. Where the private sector bears risks it cannot influence, VGF becomes insufficient and unsustainable.

Implications for Strategic Infrastructure

At first glance, strategic infrastructure appears even less amenable to PPP than ports or railways. It has no user revenue, operates in extreme environments, and is deeply embedded in national security considerations. However, a closer examination reveals the opposite. Strategic infrastructure possesses three characteristics that make it particularly well-suited to annuity-based PPP with VGF:

- Demand Certainty. Usage is driven by defence requirements, not market demand.

- Single Beneficiary. The state is the primary and often sole beneficiary.

- Performance Focus. Asset availability and reliability matter more than throughput or profit.

These characteristics eliminate the central uncertainty that undermines many commercial PPPs.

Relevance of Annuity-Based Models. Annuity-based PPP models shift the focus from revenue generation to asset availability and performance. Private partners are compensated through fixed payments, typically linked to predefined service standards. For strategic infrastructure, this approach offers several advantages:

- Eliminates traffic and revenue risk.

- Enables predictable fiscal planning.

- Incentivises construction quality and long-term maintenance.

- Preserves full government control over operations.

When combined with VGF, annuity-based models can make even the most challenging strategic projects bankable without exposing private partners to uncontrollable risks.

Reassessing the Role of the Private Sector

The role of the private sector in strategic infrastructure must be understood in limited and specific terms. Private entities are not being asked to manage security-sensitive operations or exercise sovereign authority. Their role is confined to:

- Design and construction.

- Project management.

- Long-term maintenance.

Security oversight, access control, and operational decision-making remain firmly with the state. This distinction is critical for addressing institutional resistance and ensuring political acceptability.

Comparative Perspective: India and China. China’s approach to strategic infrastructure relies on state-owned enterprises executing projects with assured financing. These entities absorb losses as a matter of policy, reflecting the primacy of strategic objectives over commercial returns. India’s institutional landscape is different. However, the functional outcome—rapid infrastructure creation backed by state support—can be approximated through VGF-backed PPP models that leverage private execution capacity within a sovereign framework.

The Need for a Dedicated Strategic PPP Framework. The preceding analysis establishes that strategic infrastructure represents a distinct category of public assets—one that cannot be effectively addressed through either conventional commercial PPPs or exclusive reliance on budget-funded EPC models. The unique combination of security imperatives, absence of revenue streams, and extreme operating conditions necessitates a dedicated policy framework for strategic infrastructure development. Such a framework must recognise that private participation in strategic infrastructure is not about profit maximisation, but about augmenting state capacity through efficient delivery mechanisms. VGF, when embedded within annuity-based PPP models, provides the structural foundation for this approach.

Core Principles for Strategic PPP Design. Any policy framework for strategic PPP must be anchored in a set of non-negotiable principles:

- Primacy of National Security. Strategic objectives must override financial considerations. Infrastructure design, execution, and operation should be guided by military requirements.

- Retention of Sovereign Control. Ownership, access, and operational authority must remain with the state at all times.

- Realistic Risk Allocation. Private partners should bear risks related to construction efficiency and maintenance, while the state retains geopolitical, demand, and security risks.

- Fiscal Predictability and Transparency. Government support through VGF should be clearly defined, capped, and structured to avoid ad hoc interventions.

- Lifecycle Performance Orientation. Long-term asset availability and reliability should be prioritised over initial construction speed alone.

These principles distinguish strategic PPP from its commercial counterparts and ensure alignment with national security imperatives.

Model Selection for Strategic Infrastructure

Based on project characteristics and risk profiles, three PPP models emerge as suitable for strategic infrastructure, each with a specific role.

- Pure Annuity + VGF. This model should be the default option for frontline strategic assets, particularly in sensitive border areas. Appropriate for:

- Border roads near the Line of Actual Control.

- Access roads to advanced landing grounds.

- Strategic bridges and tunnels in high-altitude terrain.

Under this model, the private partner designs, builds, and maintains the asset, while the government makes fixed annuity payments. VGF is used to ensure financial viability, with no reliance on user charges.

- DBFOM + VGF. This model is suitable for large, complex strategic projects requiring integrated lifecycle management. Appropriate for:

- Long, technically complex tunnels.

- Integrated logistics hubs.

- Dual-use corridors with limited civilian traffic.

By consolidating design, construction, financing, operation, and maintenance under a single contract, DBFOM + VGF encourages durability, innovation, and cost efficiency.

- Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM). HAM may be applied selectively where:

- Terrain is relatively accessible.

- There is mixed civilian and military usage.

- Partial cost sharing during construction is feasible.

However, HAM should not be treated as a universal solution for strategic infrastructure.

Institutional and Security Safeguards

One of the principal concerns regarding private participation in strategic infrastructure relates to security and control. These concerns can be effectively addressed through robust safeguards:

- Security vetting and pre-qualification of contractors.

- Restricted access protocols for sensitive zones.

- Government-controlled traffic and operations.

- Clear termination and step-in rights.

- Sovereign-backed annuity payment mechanisms.

Such safeguards ensure that private participation enhances delivery capacity without compromising security.

Fiscal and Strategic Advantages of VGF-Based PPP From a fiscal perspective, annuity-based PPP supported by VGF offers several advantages:

- Smoothing of capital expenditure over time.

- Greater predictability in budget planning.

- Reduction in upfront fiscal shocks.

Strategically, this approach enables:

- Faster infrastructure creation.

- Improved asset quality and reliability.

- Enhanced deterrence through credible connectivity.

In effect, VGF-based PPP allows India to achieve outcomes similar to China’s state-led infrastructure push, while remaining consistent with India’s institutional and democratic framework.

Implementation Roadmap

To operationalise this framework, the following steps are recommended:

- Formal Policy Recognition. Strategic infrastructure should be explicitly recognised as eligible for PPP with VGF.

- Creation of a Strategic Infrastructure Fund. A dedicated fund to ring-fence annuity payments and enhance investor confidence.

- Model Concession Agreements. Tailored contracts incorporating security clauses and performance standards.

- Pilot Projects. A limited number of projects along the northern borders to demonstrate feasibility.

- Inter-Ministerial Coordination Mechanism. Integration of defence, finance, and infrastructure planning processes.

Conclusion

Strategic infrastructure is no longer a peripheral development issue; it is a central pillar of national security. As India confronts a dynamic and challenging strategic environment, the pace and scale of infrastructure development will increasingly shape operational outcomes. Continuing to rely solely on traditional delivery mechanisms risks creating a mismatch between India’s strategic ambitions and its execution capacity.

The question, therefore, is not whether the private sector should be involved, but how it can be engaged in a manner consistent with national security imperatives. VGF provides the conceptual and practical bridge between these objectives. Success depends not on the quantum of support, but on clarity of purpose, realism in risk allocation, and institutional coherence. The choice before policymakers is not between public and private, but between traditional incrementalism and strategic acceleration.

A deliberate shift towards VGF-backed strategic PPP will signal India’s readiness to align institutional innovation with strategic necessity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

LLt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, a former DGBR, is a writer and social observer. He also pursues his passion for the creative arts in his free time.

LLt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, a former DGBR, is a writer and social observer. He also pursues his passion for the creative arts in his free time.