The debate in India on her neighbour China tends to swing between two comforting certainties: confrontation framed as resolve, and engagement dismissed as weakness. Both positions are comfortable, but analytically thin. They avoid the harder question: how does India deal with a neighbour that is stronger today, unlikely to disappear tomorrow, and impossible to ignore without cost?

The concept of Chindia emerged during a phase when economic growth masked strategic divergence. That phase is over. Yet the collapse of optimism does not remove the underlying compulsions that produced the idea in the first place. Geography, demography and economic growth remain unchanged. Nor has the fact that Asia’s stability now depends disproportionately on how its two largest powers manage each other.

China and India are not destined for a partnership. But neither are they condemned to permanent confrontation unless policy choices make it so.

Geography as Destiny, Not Rhetoric

China and India are locked into proximity by geography. No alliance, technology, or diplomatic alignment can alter that. The Himalayas separate them physically, but they also bind them strategically. Any assumption that one can permanently sideline the other misreads the region.

India’s continental reality differs from that of maritime powers. It must deal with China not as a distant challenger but as a resident power across a contested frontier. This reality imposes constraints. It also creates imperatives, chief among them, the avoidance of uncontrolled escalation.

The boundary dispute has never been a marginal issue; it has shaped threat perceptions, forced posture, and political trust for decades. Protocols and peace-and-tranquillity agreements reduced friction, but never resolved the dispute. Doklam in 2017 and eastern Ladakh in 2020 did not create the dispute, but they normalised coercive signalling and narrowed diplomatic space.

Yet even after repeated crises and sustained forward deployments, neither side has allowed escalation to run out of control. That restraint reflects not harmony but hard realism; each side understands that war between two nuclear powers with unresolved domestic priorities would be self-defeating.

Hence, the goal need not be early resolution, which is unlikely, but a stable modus vivendi. Regular political contact, reliable military communication channels, and credible disengagement frameworks are not diplomatic charity; they are safeguards against miscalculation.

Power Asymmetry and Strategic Realism

Any serious discussion of China–India relations must begin with power asymmetry. China’s economy is larger, its defence industrial base more integrated, and its ability to convert economic strength into military capability more advanced. This asymmetry matters most in a prolonged standoff, where endurance and industrial depth count as much as intent.

India’s objective cannot be parity in all domains. It must be leverage. That leverage is built over time through economic growth, institutional credibility, defence preparedness, and diversified partnerships. In the interim, managing the relationship with China is primarily an exercise in risk control.

Permanent hostility does not accelerate India’s rise. It drains attention, hardens Chinese threat perceptions, and limits diplomatic manoeuvres. At the same time, accommodation without capacity invites pressure. The space between these extremes is narrow, but it exists.

Engagement, when conducted from a position of preparedness, does not dilute deterrence. It reinforces it by reducing uncertainty. Chindia, in this sense, is not a vision of partnership. It is a strategy of containment without confrontation.

Economics: Dependency Is a Policy Failure, Not a Fate

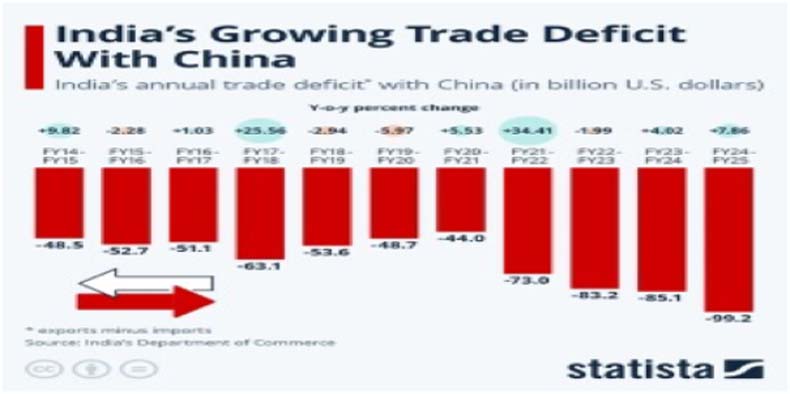

India’s trade relationship with China is often described as a vulnerability. That description is accurate, but incomplete. Dependency did not emerge overnight, nor is it irreversible. It is the result of domestic policy choices, industrial stagnation, and global supply chain dynamics.

That said, pretending disengagement is cost-free is equally dishonest. Indian industry remains tied to Chinese supply chains in sectors that directly affect growth and employment. Technology and infrastructure add further exposure. Sudden severance would damage Indian firms long before it alters Chinese behaviour. Yet, unrestrained openness would perpetuate dangerous asymmetry. The correction must be gradual and sector-specific; pharmaceuticals, electronics components, and renewable sources require different timelines and policy tools. Diversification, not disruption. Capacity-building, not gestures.

In economic terms, Chindia is not about integration or rhetoric; it is about managing exposure while buying time for domestic capacity to mature. Carefully designed coexistence in supply chains, industrial standards, and digital regulation allows both nations to keep their options open without exposing their vulnerabilities.

Strategic Competition Without Strategic Breakdown

China’s use of infrastructure financing and political leverage under the BRI framework has altered the strategic balance in South Asia. Infrastructure financing, political leverage, and expanding security ties in India’s neighbourhood have reduced New Delhi’s strategic space. For India, this has meant reduced strategic depth and higher costs for maintaining influence in its immediate neighbourhood. This competition is structural and will persist.

However, competition does not require a permanent crisis. Even during periods of rivalry, major powers historically maintained channels to prevent miscalculation. The erosion of political dialogue between India and China has increased the risk of tactical incidents acquiring strategic momentum.

Restoring leader-level engagement does not weaken India’s position. It clarifies red lines. Silence, by contrast, creates space for misinterpretation, often by military commanders operating under pressure. A managed relationship requires communication, even when trust is absent.

Multilateralism as Strategic Insurance

India and China already sit across the table in multiple forums. These platforms do not produce harmony, but they absorb friction, allowing signalling, obstruction, and limited cooperation without forcing bilateral showdowns.

For India, participation prevents isolation and sustains diplomatic flexibility. For China, it mitigates perceptions of encirclement.

Walking away from these spaces does not punish China. It reduces India’s influence. Presence allows obstruction when needed and cooperation when useful. Absence achieves neither.

Strategic autonomy demands the ability to engage rivals without becoming dependent on them or defined by them.

The Global Commons: Limited but Useful Convergence

On issues like climate change, green technology transfer, or global pandemic preparedness, India and China share enough overlapping interests to coordinate positions. This is not cooperation born of goodwill, but of shared exposure to failure. Pooling capacities; India’s pharmaceutical and research base with China’s manufacturing heft can enhance resilience within global frameworks without demanding political intimacy.

Neither China nor India benefits from climate regimes designed primarily around advanced economies. Coordination here is not idealism; it is interest alignment. Shared positions on finance, technology access, and adaptation reduce external pressure and increase bargaining power.

This is one area where rivalry is actively harmful.

What Chindia Can Realistically Mean

At its core, Chindia is not an alliance concept, nor a call for Asian harmony. It is a discipline of coexistence, managed competition bounded by restraint and periodic cooperation. What Chindia can represent is a condition of managed coexistence: predictable behaviour, bounded competition, and selective cooperation. It is not about trust. It is about restraint.

For India, this strategic balancing act allows breathing space. The priority is space to grow economically, consolidate power, and shape its region. A permanently hostile China constricts that space. A China engaged, deterred, and constrained, however imperfectly, creates room to manoeuvre.

Chindia and the Global Order

Viewed together, China and India represent an unusual concentration of power in the international system. Their account of the largest share of the population shapes labour markets, consumption, and political narratives. Geography gives them strategic reach across Asia, Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Together, they complement each other on rich history, vibrant economies, large militaries, advanced technological bases, and nuclear deterrence. Their decisions increasingly affect trade flows, energy security, military balance, and rule-setting. Any sustained stabilisation between the two would reduce the ability of the United States to play one against the other, complicating alliance management and accelerating a shift away from a US-dominated Asian balance, without creating a unified alternative pole.

Conclusion: Choosing Control Over Confrontation

The future of Asia will be shaped less by declarations and more by discipline. China and India will compete. That competition is unavoidable. What is avoidable is allowing it to spiral into confrontation and perpetual instability. The real test lies in resisting the temptation to simplify the relationship into binaries.

Finding limited common ground with China does not imply optimism about Chinese intentions. It reflects realism about Indian interests. Strategy is not built on sentiment. It is built on managing constraints.

Chindia, stripped of illusion, is not about convergence. It is about containment without collapse. That is not a weakness. It is a strategy.

In the end, Chindia is neither a dream nor a delusion. It is the strategic necessity of coexistence between two permanent neighbours, fated to shape Asia’s century together, whether they choose to manage reality or be trapped by it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.