The term Global South has emerged as a unifying identity for many of the countries it encompasses. This unification has led to the United Nations’ South-South Cooperation, a coalition of Global South countries whose main goal is to help solve mutual challenges such as poverty, population growth, war, disease, and border issues. Countries involved in the SSC become more self-reliant, strengthen their technological capabilities, and become better able to participate in the global economic marketplace.

Spearheaded by India, the Global South, an unofficial yet increasingly recognised group of countries from Central and South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania are articulating their common concerns. How significant is their growing influence in a rapidly changing world order?

In an age where global punditry is focused on the emerging duopoly of America and China, or G2 as it is being christened, there is, equally, increasing focus on the emergence of the so-called Global South. While it is not a geographical entity—some states that are aligned to the global south are in the northern hemisphere—there is a common agenda, mainly economic because most of them are underdeveloped or developing countries as categorised by the IMF and World Bank, but also the common desire to have a greater voice in world affairs.

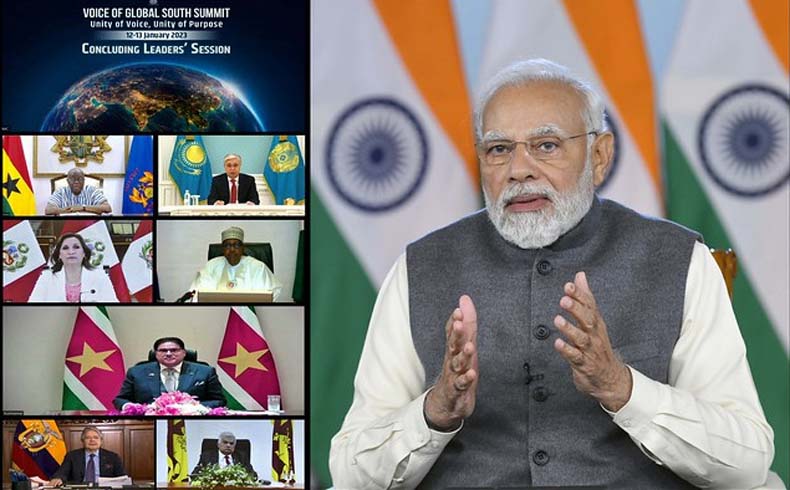

Leading the way is India. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has hosted three summits representing “the voices” of the global south. Speaking at the 17th BRICS Summit in July 2025, he emphasized that two-thirds of humanity from the Global South remain underrepresented in 20th-century global institutions, calling for urgent reforms to bodies such as the United Nations Security Council, the World Trade Organization, and Multilateral Development Banks. He affirmed that under India’s 2026 BRICS presidency, the concerns of the Global South would be a central priority, reflecting a “people-centric and inclusive vision for global governance.”

The term Global South has gained prominence as older classifications like “Third World” became less relevant or were perceived negatively. It provides a way for these nations to advocate for their interests on the global stage, moving away from a narrative dictated by the West. It also serves as a shorthand for a wide range of shared goals, from economic cooperation to advocating for a more multipolar world system.

The closest parallel was the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) created during the Cold War to promote the interests of developing countries, founded by leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Yugoslavia’s Josip Broz Tito, to distance themselves from the two superpowers of the time, America and the Soviet Union. That evolved into the G77, a group of developing countries established in the 1960s to articulate and promote their collective interests at the United Nations. That, in turn, has expanded into what is being labelled the Global South, developing countries, plus China, representing a significant portion of the world’s population.

The closest parallel was the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) created during the Cold War to promote the interests of developing countries, founded by leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Yugoslavia’s Josip Broz Tito, to distance themselves from the two superpowers of the time, America and the Soviet Union. That evolved into the G77, a group of developing countries established in the 1960s to articulate and promote their collective interests at the United Nations. That, in turn, has expanded into what is being labelled the Global South, developing countries, plus China, representing a significant portion of the world’s population.

Led by countries like India, Brazil and South Africa, which has just hosted the G-20 summit in Johannesburg, leaders of the Global South are displaying a renewed willingness and ability to challenge the dominance of the West. Leigh Anne Duck, co-editor of Global South, argued that the term is better suited at resisting “hegemonic forces that threaten the autonomy and development of these countries.” Historically, the region has lagged in economic development; however, recent trends show that several nations within the Global South are surpassing their regional peers and some Global North countries in economic performance and global influence.

There is also the troubling question of China being part of the global south movement. China identifies as part of the Global South, and many analyses consider it a key player within the group due to its economic size, but it is also seen as an outlier due to its significant global power. China aligns itself with the Global South through its diplomatic rhetoric, emphasizing a shared history of colonialism and inequality, but its actions are often seen as those of a traditional hegemonic power, which creates a contradiction. While China uses its Global South identity in its foreign policy to counter the United States and other Western powers, its categorization in the Global South remains complex. While it officially identifies as part of the Global South for diplomatic purposes and is included in many lists of Global South countries, its economic and military power places it in a unique position, distinguishing it from many of its peers in the group.

In fact, The United Nations’ Finance Centre for South-South Cooperation maintains arguably the world’s most reliable list of Global South countries. In 2022, the list included 78 countries, which are referred to as the “Group of 77 and China.” Since then, a number of other like-minded countries have declared themselves as part of the grouping. When India hosted the Voice of the Global South summit last year, 125 countries were involved. India hosted the first summit in January 2023, followed by the second in November 2023, and the third in August 2024, with the theme “An Empowered Global South for a Sustainable Future”.

In fact, The United Nations’ Finance Centre for South-South Cooperation maintains arguably the world’s most reliable list of Global South countries. In 2022, the list included 78 countries, which are referred to as the “Group of 77 and China.” Since then, a number of other like-minded countries have declared themselves as part of the grouping. When India hosted the Voice of the Global South summit last year, 125 countries were involved. India hosted the first summit in January 2023, followed by the second in November 2023, and the third in August 2024, with the theme “An Empowered Global South for a Sustainable Future”.

While it does not have a single leader or a formal governing structure like the G7 or United Nations or a secretariat like NAM had, it includes nations with varying levels of development and economic power linked by shared experiences of colonialism and the struggle for a more equitable global order. Collectively, the Global South is flexing political and economic muscles that the “developing countries” and the “Third World” never had. As former G-20 sherpa Amitabh Kant wrote recently in an op-ed: “There was a deeper strategic objective during India’s presidency of the G-20: integrating the voice and priorities of Global South into the centre of global decision-making.”

In September, 2025, speaking at the High-Level Meeting of Like-Minded Global South Countries in New York, India’s foreign minister S Jaishankar, said: “We meet in increasingly uncertain times, when the state of the world is a cause for mounting concern for member states. The Global South in particular, is confronted with a set of challenges which have heightened in the first half of this decade. Most of all, the rights and expectations of developing countries in the international system, which has been so assiduously developed over many decades, are today under challenge. So as like-minded Global South countries, we today approach world affairs united, and through a broad set of principles and concepts.” These included fair and transparent economic practices that democratize production and enhance economic security, A stable environment for balanced and sustainable economic interactions, including more South-South trade, investment and technology collaborations, and a resilient, reliable and shorter supply chains that would reduce dependence on any single supplier or any single market.

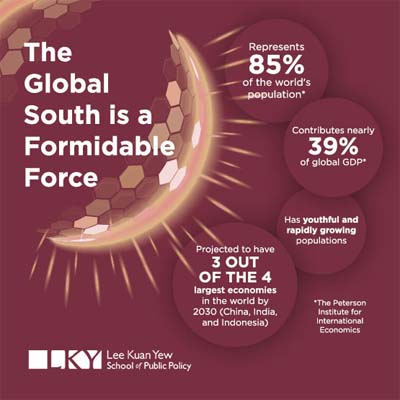

Alvaro Mendez, co-founder of the London School of Economics and Political Science’s Global South Unit, has written extensively on the emergence of the bloc and the empowering aspects of the term. In an article, Discussion on Global South, he looks at emerging economies in nations like China, India, Mexico and Brazil and analyses predictions that by 2030, 80% of the world’s middle-class population will be living in developing countries. The Global South also holds 70% of the world’s wind and solar energy potential and 50% of minerals necessary for global energy transition.

As Christina Figueres, a senior diplomat from Costa Rico said recently: “The era when American politics could make or break global cooperation is over. This time the Global South is leading the way.”

There is also growing recognition that the global balance of power is shifting; the 2023, the UK government review of defence, security and foreign policy identified this as one of the four trends that would shape the international environment.

Some commentators talk of a new era of great power competition between the United States, China and Russia, recalling how the world divided into American and Soviet spheres of influence during the Cold War. Can the Global South step into the breach? It is not a formal bloc but collectively, their voices are starting to count in global affairs. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has also spoken of the need to strengthen the voice of Africa and the Global South in the broader multilateral system.

India’s G20 theme, which focused on amplifying the voice of the Global South, was “One Earth, One Family, One Future”. The theme for the 3rd Voice of Global South Summit in 2024 was: “An Empowered Global South for a Sustainable Future”. The core, collective ambition is to create a stronger, more unified voice for the Global South on the world stage.

In common usage, the label amalgamates a remarkably heterogeneous group representing around two-thirds of the world’s population and spreading across vast expanses of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Its ostensible members range from Barbados to Bhutan, Malawi to Malaysia, Pakistan to Peru, and Senegal to Syria. The category encompasses both major emerging powers, including aspirants to UN Security Council seats such as Brazil, India, and Nigeria, as well as small states like Benin, Fiji, and Oman.

The US-based think tank, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, did a deep analysis of the grouping recently which pointed out that many critics say that the concept purports to capture an array of nations that differ markedly in their governing systems, economic circumstances, strategic alignments, and cultural identities. However, the study went on to conclude that such critiques should not obscure the term’s “continued political salience and symbolic potency,” adding: “Across the decades, the concept of the Global South has resonated with governments and citizens of lower- and middle-income countries because it is an expression of perceived exclusion from—and rejection of—enduring hierarchies in world politics. Historical analysis thus illustrates that, rather than using the Global South to mean a rigid grouping of nations, it is more helpful to understand it as an organizing principle to guide a reimagining of a more just international economy and world order. Appreciating the continuity between twentieth-century anticolonial movements and contemporary political issues clarifies the perspectives and choices of many in the Global South for policymakers in the United States and the rest of the so-called Global North. To some in the world, the central divide in the international sphere remains that between the dominant North and the aggrieved South, rather than that between democracies and autocracies.”

As Jean-Noël Barrot, French Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs, wrote in an article in February 2025: “Some may argue that the world is divided between a “Global North” and a “Global South”. But what exactly is meant by that? Of the 20 leading global economies, seven are in the “South.” According to IMF data (in purchasing power parity terms): four of the world’s 10 largest economies are in the global south: China, India, Indonesia and Brazil. The main stumbling block seems to be the huge diversity, in economic, political and diplomatic terms, between the nations that are currently being classified as the global south.

However, as Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva who, along with Prime Minister Modi and South Africa’s Ramaphosa, are striving to give the Global South a larger voice in world decision making, stated: “There are those who question the concept of the Global South, saying that we are too diverse to fit together. But there are many more interests that unite us than differences that separate us.”

Other critics have argued that such a grouping, and its objectives, hinder it from dealing effectively with western powers led by the US. In fact, India, Brazil and South Africa have been slapped with the highest tariffs by the US administration.

Audrey Wilson, managing editor at Foreign Policy magazine which has published articles either using the term or discussing its merits or demerits, says that while many analysts question its legitimacy, “what is certain is that the global south will remain a central figure in diplomacy and summitry in the coming years.”

In its latest article on the eve of the November 22 G-20 summit in Johannesburg, Sophie Eisentraut, head of research and publications at the Munich Security Conference, wrote: “As the G-20 summit approaches, the countries of the global south may already be starting to fill the United States’ empty chair. Europeans would do well to pay attention.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dilip Bobb is a former senior managing editor, India Today (1975 -2010), and Group Editor, Features and Special Projects, Indian Express (February 2011-October 2014)

Dilip Bobb is a former senior managing editor, India Today (1975 -2010), and Group Editor, Features and Special Projects, Indian Express (February 2011-October 2014)