“Stick to the big questions, don’t get bogged down in the details.” — Tony Sanford

India enters FY2025–26 at a critical point, with early data highlighting strong macroeconomic momentum but also revealing significant structural challenges. MoSPI estimates real GDP growth of 7.8% in Q1 FY26, the highest in five quarters, driven by services (~9.3%), stable manufacturing (~7.7%), and a broad-based GVA increase of 7.6%. Agriculture grew by approximately 3.7%, construction by about 7.6%, while mining contracted by 3.1%.

On the demand side, private consumption increased by around 7.0%, which is slower than the previous year but still supported by strong urban spending. Investment (GFCF) grew by about 7.8%, and government consumption rose nearly 10% in nominal terms. Given the strong Q1 base and favourable domestic demand, we expect growth to stay within the high-6% to low-7% range in the near term, though external risks remain. Overall, Q1 was robust, led by services and the rebound in infrastructure/construction capital spending.

Private consumption, while still solid, slowed compared to the previous year, and investment is improving but not yet fully broad-based. For Q2, a moderate increase in urban consumption ahead of festivals, continued but modest rural demand, and ongoing public investment are expected, but private investment may still be lagging.

Reliability of India’s Data

India’s macroeconomic data is broadly credible and improving, National Accounts follow UN SNA 2008 standards. India has a large, well-institutionalised statistical system (MoSPI, NSO, RBI). Quarterly GDP estimates are produced with regular revisions—first advance, second advance, provisional, revised—which increases accuracy over time. Use of GST, corporate data, MCA-21 database post-2015 has improved formal sector measurement. But it also faces known structural weaknesses that make certain indicators less precise or less timely than in advanced economies. The large informal sector (≈45–50% of the economy) complicates measurement. The base year is outdated (2011–12); newer one is still pending.

Quarterly GDP for agriculture, informal services, and SMEs often relies on proxies rather than actual surveys. The corporate data coverage in MCA-21 has validation issues, as noted by the Rangarajan Committee and the National Statistical Commission (NSC). The GDP revisions can be large, signalling initial under- or overestimation. India’s inflation measurement is high-quality and trustworthy, but weight updates are overdue.

Industrial Production (IIP) data is moderately reliable but volatile. In sum, India’s statistical agencies are generally professionally independent, and international bodies (IMF, World Bank) consider the data broadly credible, though in need of modernization.

Q2 Outlook: Festive Momentum and Public Capex Support

While official numbers are awaited, early indicators suggest Q2 held up well. Urban demand appears to have strengthened ahead of the festive season, rural consumption is showing the first signs of a meaningful pick-up, and public investment remains the economy’s most reliable pillar. States raised capex by 23% in Q1, while the Centre has already exhausted over a third of its capex allocation. Private capex, however, remains selective—project announcements are large, but execution is uneven.

Consumption remains the fulcrum of the economy, accounting for 55–60% of GDP. As incomes rise and balance sheets strengthen, the consumption cycle is broadening. Rural consumption growing 7.7% year-on-year in Q2, the fastest in 17 quarters, is particularly significant, signalling a paradigm shift after several soft years. Softer inflation, easier credit, and heavy promotional activity in automobiles, appliances, and electronics have improved sentiment across both urban and rural markets. High-frequency indicators, such as E-way bills (up 26%) and GST collections (near ₹1.9 lakh crore), point to GDP growth of around 7–7.2% in Q2.

Trade Headwinds: U.S. Tariffs and Their Ripple Effects

The sharpest external risk now comes from the U.S. decision to impose tariffs of up to 50% on a slate of Indian exports, including textiles, gems and jewellery, leather and seafood. The exposure is sizable at roughly $60 billion, and some sectors could see steep volume declines. While the direct drag on growth may be limited given the economy’s consumption-heavy structure, the indirect effects on MSMEs, employment and export-linked investment cannot be dismissed. This unsavoury episode reinforces the urgency of diversifying export markets and upgrading domestic competitiveness.

GST Rationalisation and Its Trade-offs

The September 2025 GST rationalisation covering consumer durables, small cars, ACs and several services has boosted sentiment and eased household budgets. The revenue hit, estimated at ₹93,000 crore, is partly offset by improved compliance and slab restructuring. The move helps reduce inverted duty structures and gives labour-intensive sectors some breathing room. But states, already facing tight budgets, remain worried about revenue loss, and some form of calibrated compensation may become necessary.

Monetary Policy and Inflation: A Window of Comfort

With inflation easing sharply—headline CPI fell to 3.16% in April—the RBI cut the repo rate to 6.0% and adopted an accommodative stance. Lower rates are starting to ease borrowing costs, though transmission remains patchy. While India’s disinflation largely reflects benign food prices, a good monsoon and subdued global commodities, extremely low inflation also carries risks: weaker nominal GDP, slower revenue growth, and pressure on corporate profitability. Core inflation remains sticky at 4–4.5%, signalling residual demand-side and cost pressures.

Grammar of Development: Growth Prospects

FY26 growth is projected in the 6.3–6.8% range, with upside if consumption and investment strengthen, and downside if global stresses intensify. In the medium term, sustained reforms in infrastructure, labour, logistics, and ease of doing business are essential to lift growth into the 7%+ range. There are several upside drivers, which provide an impetus to the process of growth. Such drivers include strong household demand (urban + rural), accelerated private capex under PLI/Make in India, low inflation enabling further monetary easing, and favourable global commodity dynamics.

Downside Risks

Downside risks are material: the recent U.S. tariffs already caused a near 12% drop in Indian merchandise exports to the U.S. in September. If trade diversion is slow and global headwinds intensify, growth could slip. A sharp weather or food-supply shock could reignite inflation and squeeze rural demand. Additionally, fiscal space is constrained by revenue pressures, like slowing nominal GDP growth and GST rationalisation, raising risks to the quality of public investment. These factors make it necessary to address emerging macro imbalances and their attendant granular implications.

Manufacturing: The Long-Standing Weak Link

“Think globally but act locally.” — Prof. Oladele Osibanjo

India’s manufacturing share has remained stuck at ~15% of GDP for over thirty years—driven by deep structural issues rather than temporary cycles, despite multiple policy pushes. High logistics and power costs, complex land and labour frameworks, fragmented supply chains, sub-scale firm distribution, and limited integration into global value chains have long bedevilled the sector. This stagnation reflects structural constraints rather than cyclical weakness. The sector faces high logistics and power costs, complex land and labour regulations, and fragmented supply chains that undermine competitiveness. A large share of firms operate at sub-scale levels, limiting productivity gains, technology adoption, and formalisation. Manufacturing employment has similarly underperformed, with limited absorption of surplus labour from agriculture.

Global dynamics have also shaped outcomes. China’s scale advantages, deeply embedded supply networks, and aggressive export orientation made it difficult for India to position itself as an alternative. Further, India’s domestic demand–driven growth model has historically prioritised services, which are more flexible and less capital-intensive.

PLI successes in electronics and renewables show promise, but scaling up requires faster trade facilitation and customs reform, stronger MSME linkages and technology diffusion, deeper skilling and industrial workforce reforms, and investment in ports, logistics, and power reliability. Complementary measures include infrastructure investment (ports, logistics, power), production-linked incentives (PLI) schemes in 14 priority sectors (electronics, pharmaceuticals, auto-components) supported by a combined outlay of ₹1.97 lakh crore, export-promotion schemes, simpler regulatory regime, land/labour reforms, and tax/indirect-tax support (such as, GST rationalisation).

Manufacturing grew 7.7% in Q1, but export-sector stress from U.S. tariffs increases the urgency for domestic capacity building and diversification. A meaningful manufacturing revival is essential for job creation, investment depth, and sustained 7–8% GDP growth over the long haul.

With firms looking to diversify away from China/other regions, India is positioning itself as an alternative manufacturing base and addressing the contextually significant issue of supply-chain diversification. The manufacturing push under Make in India and related incentives may spur greater foreign direct investment (FDI) and domestic capex in manufacturing, which is important because manufacturing historically has had lower share in GDP growth versus services/consumption.

For labour-intensive manufacturing (textiles, apparel, leather, furniture), the recent GST rate rationalisation and indirect tax relief provide a competitiveness boost.

But challenges remain: cost competitiveness (labour, power, logistics), land and infrastructure bottlenecks, variable quality of the regulatory environment, global demand uncertainty.

The current export headwinds (e.g., U.S. tariffs) increase the urgency for the manufacturing sector to focus both on domestic demand and export diversification.

If manufacturing can pick up meaningfully, it would help raise India’s investment rate, generate jobs (especially for the younger workforce), improve productivity, and make growth more inclusive, thereby supporting a structural shift from consumption-led to investment/manufacturing-led growth.

The Make in India agenda is well-aligned with the structural need to boost manufacturing. The current macro backdrop (moderate inflation, easing financing costs, policy support) is favourable. However, the realisation of the manufacturing leap will depend on investment rollout, implementation efficiency, global demand, and how quickly domestic manufacturing can scale up. Unlocking manufacturing growth is essential for job creation, export dynamism, and sustained 7–8% GDP growth over the medium term.

Fiscal Position and Budget Priorities

GST revenues touched ₹22.08 lakh crore in FY25, reflecting underlying buoyancy. The Centre remains committed to its fiscal consolidation roadmap, targeting a deficit of 4.4% of GDP in FY26 alongside a record ₹11.21 lakh crore capex outlay. The first quarter saw a 52% jump in central capex and strong state spending as well. The emphasis remains on transport, logistics, and manufacturing-supportive infrastructure.

Fiscal pressures, however, remain, with slower nominal GDP, uncertainty over GST revenues post-rationalisation, and high state-level deficits that could complicate consolidation in the coming years.

Broad-based Inclusive Growth

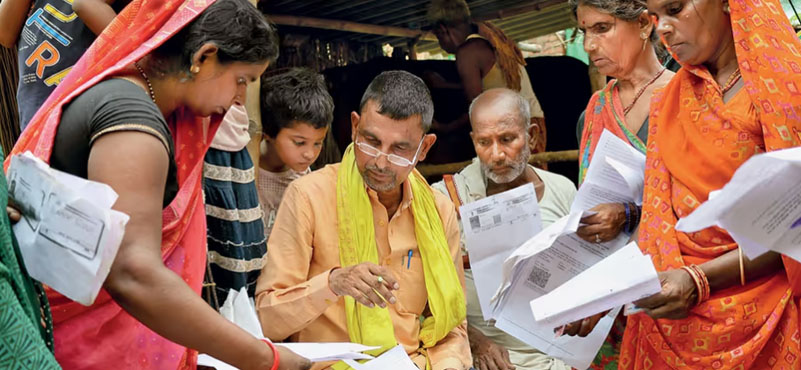

India has made significant progress in recent years in advancing inclusive growth, which has always been a central objective of our development planning. There has, however, been a sharper focus on financial inclusion and digital empowerment in the last 10-15 years.

One of the key breakthroughs has been the successful implementation of the JAM Trinity—Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar, and Mobile connectivity. This initiative has brought about a quiet revolution by improving access to banking and government services, especially for the underserved. It has also gained recognition from global institutions like the World Bank and the IMF.

Going forward, efforts must continue to build on this foundation. The JAM framework has been instrumental in reducing leakages, improving efficiency, and ensuring that benefits reach the intended sections of society. Strengthening and expanding this system will be crucial for sustaining inclusive growth.

Growth reduces poverty but does not automatically reduce unemployment, inequality, or regional imbalances. To make growth broad-based you need a deliberate mix of: labour-intensive public investment, demand-driven skilling and manufacturing promotion, stronger social protection and redistribution, regional infrastructure and decentralised planning — all underpinned by better data and outcome-based accountability. invest in people and strengthen workforce outcomes.

Today, governments must focus on broad-basing economic growth to ensure it benefits all sections and regions of society. Strengthening the MSME sector, creating an enabling ecosystem for inclusive development, and leveraging the role of banks and financial institutions as catalysts for transformation are essential. These elements are key to addressing inequality and fostering sustainable, equitable growth.

Lexicon of Change-Outlook and Policy Imperatives

With structural tailwinds like demographic dividend and a rising middle class; urban–rural convergence; shift toward services and the experience economy; digitisation, fintech, and wider distribution; and durables and aspirational goods upcycle with high income elasticity and strong supply-chain multipliers, India stands at an inflexion point. But despite India’s robust macro fundamentals, the road ahead demands precision rather than complacency. The key priorities include improving the quality of public spending, reviving private investment through regulatory clarity, accelerating reforms in logistics and factor markets, and integrating more deeply into global value chains.

Growth around the mid-6% range is achievable and sustainable but unlocking the next stage of 7–8% growth with broad-based prosperity requires firing on all growth cylinders: consumption, investment, manufacturing, exports, and public spending. The reform agenda must provide a renewed thrust on labour/formalisation (digital platforms, gig economy, MSME formalisation), supply-side/logistics improvements, and deeper financial inclusion/credit access at this defining moment.

While fiscal consolidation under the FRBM framework must continue, the bigger priority is to reignite economic “animal spirits” through execution-driven reforms, stable macro policy, and a relentless push to build competitive, scalable manufacturing ecosystems.

The larger shift required is one of mindset: embracing execution-led reforms, building competitive industrial ecosystems, and focusing on sustained rather than episodic growth. If India can align these forces, the coming decade could mark a significant transformation in the country’s economic trajectory. As Robert Frost wrote eloquently in his poem Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening published in his collection ‘New Hampshire’ (1923), we would like to rest there awhile, but we must move on because the cycle of life and economy never ends, the wheel marches inexorably onwards, and we must adapt to changing circumstances and the evolving world- a world, where change is the only constant, a world of ebb and flow, churn and swirl, a roller coaster ride of sorts.

“The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma is Chief Economist, Infomerics, India. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 250 publications and six books. His views have been cited in the Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma is Chief Economist, Infomerics, India. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 250 publications and six books. His views have been cited in the Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.