Heritage, not a Relic; Responsible Tourism should Preserve this Living Rhythm, as a shared responsibility.

Tourism in India unfurls not as a simple act of travel across landscapes, but as an intricate dialogue with memory, imagination, and civilisational wisdom. It is not the passage of visitors through time-worn sites, but a deeper communion with the spirit of place, crafted over generations and delicately held by communities who live and breathe heritage. In this conversation, the inclusion, upskilling, and empowerment of knowledge bearers and creative communities are not optional; they are essential. Without their presence, tourism remains a hollow journey; with them, it becomes a living force aligned with the spirit of Mission Viksit Bharat – Developed India.

Cultural heritage, whether it flows through rituals and cuisine, is etched into temple walls, sings through folk music, or now flickers across digital screens, emerges as a profound human response to geography. Each tradition, each expression, is shaped by the terrain that birthed it.

India, encompassing approximately 2.9 per cent of the Earth’s surface, is a living atlas of physical variety: majestic mountain ranges, ancient plateaus, fertile plains, a long coastal line, winding rivers, searing and frozen desert, saline stretches, and dense forests. These terrains have given rise to an equally vast spectrum of cultural expression. Over 1,900 languages flow through the lives of 3,000 castes and nearly 25,000 sub-castes. Thousands of Scheduled Tribes, and several hundred denotified, nomadic, and semi-nomadic communities form a vibrant cultural landscape unmatched in its complexity and depth. This diversity, unique to India, is not merely decorative; rather, it serves as a foundational element that reflects centuries of adaptation to various environmental, political, economic, and social realities.

This diversity is not merely decorative; rather, it serves as a foundational element that reflects centuries of adaptation to various environmental, political, economic, and social realities. The outcome of this complex interplay is a nation enriched by an extraordinary array of natural and cultural heritage. One aspect presents a landscape that invites wildlife exploration and adventure. At the same time, the other reveals a rich tapestry woven from rituals, festivals, culinary traditions, artistic skills, and local aesthetics, all of which create fertile ground for immersive cultural heritage tourism experiences and the development of emerging forms such as sports tourism. Additionally, India’s digital archives, encompassing photography, cinema, and multimedia expression, further broaden the horizons of both living tourism and digital engagement.

The vast constellation of heritage forms an intricate lattice of human creativity and ecological interdependence. Tourism policy, when centred around the participation of local creative and intellectual communities, evolves from management to stewardship. In aligning itself with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, India crafts a tourism narrative that promotes economic vitality, environmental guardianship, social inclusion, and infrastructural transformation.

This alignment breathes life into the vision of Viksit Bharat—a nation defined not only by economic progress but by cultural and ecological wisdom.

As the World Tourism Organisation affirms, “Tourism bridges cultures and fosters understanding between people.” In India’s case, this bridge is more than symbolic. It carries the weight of livelihoods, the voice of traditions, and the power to rewrite development through inclusion. Tourism becomes a strategy to alleviate poverty, ensure sustainable resource use, protect natural and cultural heritage, and promote shared prosperity. This potential for shared prosperity through tourism is a reason for optimism about India’s future.

Within the umbrella of tourism, cultural heritage tourism stands out as the most evocative. It is here that India’s richness finds its most profound expression, where heritage is not a relic but a living rhythm of everyday life. Preserving this living rhythm through responsible tourism is a shared responsibility.

The Living Silence of Silent Valley

Silent Valley, nestled within the mist-laced Western Ghats of Kerala, holds a name bestowed in 1847 by the Scottish botanist Robert Wight. Struck by the absence of cicadas, he named it Silent Valley. Yet the silence is not absence, it is presence. It is a stillness dense with life, a hush that breathes with the wisdom of the forest and those who know its language.

Among them is Maari, a Muduga tribesman with extensive experience as a forest watcher, and in his presence, the forest transforms into a manuscript, vivid and rich with meaning. He meticulously examines the bark of ancient trees to uncover the scars left by elephants, interprets the claw marks that indicate the passage of tigers, and gestures toward the flicker of dragonflies that signify the purity of the stream, as each sound and each sign becomes a verse in an unwritten poem that has been shared from one generation to the next.

Among them is Maari, a Muduga tribesman with extensive experience as a forest watcher, and in his presence, the forest transforms into a manuscript, vivid and rich with meaning. He meticulously examines the bark of ancient trees to uncover the scars left by elephants, interprets the claw marks that indicate the passage of tigers, and gestures toward the flicker of dragonflies that signify the purity of the stream, as each sound and each sign becomes a verse in an unwritten poem that has been shared from one generation to the next.

Maari’s knowledge, which he has acquired not in conventional classrooms but instead beneath the expansive canopies of the forest, is a form of science deeply rooted in a sense of belonging. The Muduga and other indigenous communities hold profound insights into the complexities of ecosystems, recognising hundreds of species not by their Latin names but by their vital roles in the delicate rhythm of the forest. This knowledge resists codification; it is a form of understanding that can only be fully experienced and lived.

Yet these communities, essential to the forest’s health, are often displaced in the name of conservation. Buffer zones replace homes, severing ancient bonds between people and place, and this misunderstanding of sustainability is both tragic and counterproductive, since the forest has always been sustained by its people, and removing one harms the other.

As Viksit Bharat emerges, a foundation rooted in inclusion becomes essential. Sustainable tourism must leverage the ecological wisdom of indigenous communities not as an act of charity but as a model for mutual survival. Training forest dwellers to serve as guides, researchers, and interpreters creates employment opportunities while strengthening the ethical fabric of tourism; this initiative inspires knowledge communities to preserve cultural identities that are often lost in the relentless pursuit of political, social, and economic advancement. In this context, visitors learn not merely to see but to truly perceive.

Maari’s enduring partnership with the Forest Department, along with its recent connections with travellers, presents a vision of inclusive conservation that reflects UNESCO’s ideals for Natural Heritage, where biodiversity intertwines with cultural knowledge. In this context, the forest transcends a mere preserved artefact; it serves as a vibrant living classroom.

The stillness of Silent Valley is far from empty; rather, it resonates with the sound of balance, characterised by the rustling of a bird’s wing, the gentle ripple of water, and the soft step of a barefoot guide. This harmony represents the essence of sustainability, and to truly appreciate it, tourism must engage not with cameras but with conscience.

Weaving Maritime Memories: Local Knowledge and Sustainable Heritage Tourism

On the windswept coast of Mandvi in Kutch, Gujarat, memory is preserved not in museums but in the textures of salt, wood, and song, as the Kharwha boat builders and sailors uphold maritime traditions that have connected India to the world for centuries. Among them is Shivji Kharwha, a nonagenarian whose life story is etched into the keel of every vessel he has touched; having captained his first ship at the tender age of twelve, he now crafts miniature dhows in his Ship Model Shop located near the old port, serving as a living archive that encompasses monsoon voyages, whispered prayers, and the vivid imagination of encounters with mermaids and water spirits.

His narratives also evoke the scent of Yemen’s Socotra Island, a once-sacred destination for Kutchi sailors, and regarded as the dwelling place of Socotra Devi, Sikotar Maa, the guardian of the seas. Known as the “Island of Bliss,” this location was integral to an ancient maritime pilgrimage during which sailors carried model boats as offerings, presenting them upon arrival as expressions of gratitude and reverence.

These maritime journeys, which extended for months and crossed the Arabian Sea to the East African coast, facilitated trade in spices, ivory, and stories. Historical records affirm these connections, as evidenced by inscriptions found in Socotra’s Hoq Cave, carved in Brahmi script between the first century BCE and the sixth century CE. It is believed that the name “Socotra” may derive from the Sanskrit term Dvipa Sukhadara.

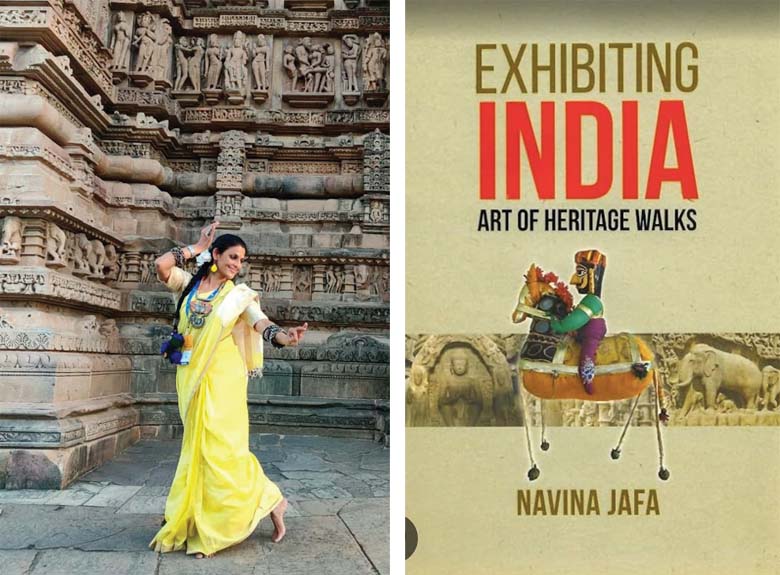

The veneration of Sikotar Maa, through the offering of a small ship model, persists among seafarers in Gujarat, with her coastal shrines still receiving prayers for safe passage. Yet, this living tradition is frequently overlooked in mainstream heritage narratives and holds significant promise for cultural tourism. The publication ‘Exhibiting India: The Art of Heritage Walks’ by the Government of India emphasises how such stories can be thoughtfully curated through the involvement of local communities; rather than merely polishing monuments in isolation, development must nurture the human heritage they embody.

Maritime memory is not a closed chapter; rather, it serves as a compass, illuminating Viksit Bharat’s path toward envisioning sustainable tourism as both anchor and sail. It resonates with echoes of a time when India was a formidable player on the global stage, drawing upon ancient wisdom while adeptly navigating the tides of the future. This rich heritage not only informs our present endeavours but also empowers us to chart a course that honours our past while embracing the opportunities of tomorrow.

Khajuraho: Reclaiming the Living Pulse of Heritage

Khajuraho transcends its characterisation as merely a site of stone and sculpture; it embodies a sanctuary where form is transformed into dance and rhythm resonates within the very walls of its temples. Yet, in the relentless pursuit of modernising heritage experiences, numerous such sites have forfeited their essence to the allure of superficial spectacle. Laser shows now illuminate spaces that once reverberated with the melodies of folk songs, as mechanical precision supplants the touch of human creativity.

This transformation stifles the living continuity of culture. Rather than depending on electronic extravaganzas, Khajuraho, along with myriad other heritage sites, could be revitalised through the rich artistry of puppeteers, village theatre, and regional performers. These artists, deeply rooted in oral tradition and community memory, offer an authenticity that no projection can ever replicate.

Implementing multilingual side screens that offer translations in Hindi, English, and regional dialects would facilitate meaningful engagement from diverse audiences without compromising linguistic or cultural integrity. The loss of any language represents the disappearance of an entire world, and the erosion of linguistic diversity is not merely superficial; it poses an existential threat. In the absence of such diversity, Viksit Bharat risks losing the very voices that imbue it with depth and resonance.

The inclusion of marginalised and denotified communities in tourism experiences reconfigures heritage into a shared memory rather than a commodified fragment. When folk traditions are relegated to hotel lobbies, they become mere decor; however, when intricately woven into the fabric of the heritage landscape, they restore dignity, significance, and continuity.

Moreover, the organisation of dance and music festivals at prominent sites such as Khajuraho warrants a more thorough examination. Committees must encompass scholars and practitioners with a deep understanding of history, performance, and iconography. The programming should be aligned with the philosophical essence of each monument, ensuring a harmonious balance between solo and group performances. The Natya Shastra acknowledges solo performance as a medium for creative spontaneity and an intimate dialogue between artist and audience.

Such structural reforms are not mere surface-level adjustments; they are foundational. Only through recalibrating the interaction between monument, performance, and community can India’s festivals evolve into sites of knowledge rather than mere entertainment.

Building Viksit Bharat Through Living Heritage

The vision of Viksit Bharat cannot thrive solely on restored stone. Heritage revitalisation, while essential, must pair with the development of human infrastructure that encompasses community empowerment, respect for tradition, and skill cultivation. The frameworks of tourism, including roads, hotels, and digital platforms, serve merely as skeletal structures; without the vibrancy of living culture, such frameworks lack true essence.

Laser shows may capture attention, but cannot replace the profound warmth of human expression. These spectacles illuminate without providing real enlightenment. Imagination is essential, imagination that positions local communities at the core of tourism. When skilled, creative, and knowledgeable individuals become central actors rather than background figures, tourism becomes a vibrant cultural economy.

In this way, employment flourishes with dignity, and systems of knowledge endure beyond the margins. India’s cultural intelligence can then shape global perspectives and foster domestic prosperity. During times when other sectors falter, tourism emerges not just as a safety net but as a symbol of vitality, identity, and inclusion. This sector tells stories in silence, forges livelihoods in barren fields, and revives national identity when the present seems to forget.

Rooted in its people, tourism embodies the nation’s heartbeat. Let that heartbeat resonate with strength, echoing the industriousness of artisans, the evocative tales of storytellers at twilight, the graceful movements of dancers in temple courtyards, and the contemplative gazes of sailors under starlit skies. Viksit Bharat must rise not only from restored ruins but from the resounding voices of those who have never abandoned their roots.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

Dr Navina Jafa is a distinguished authority in heritage tourism, an acclaimed Kathak dancer, and the author of Exhibiting India: Art of Heritage Walks (Government of India, 2024). She has pioneered the field of experiential heritage walks in India, earning accolades such as the ICONIC Award 2025 for Heritage Tourism. As a Fulbright scholar at the Smithsonian Centre for Folklife and Cultural Heritage in Washington DC, she developed innovative approaches for safeguarding intangible cultural skills through heritage tourism. Dr Jafa’s work forges connections between heritage conservation, sustainable tourism, and the performing arts. Celebrated by eminent institutions, her interdisciplinary initiatives empower communities via culture and education, having trained over 300 teachers in the integration of heritage.