“Strength is not in merging theatres, but in dominating the battlespace and victory belongs to the nation that fuses its battlespace, not just its forces.”

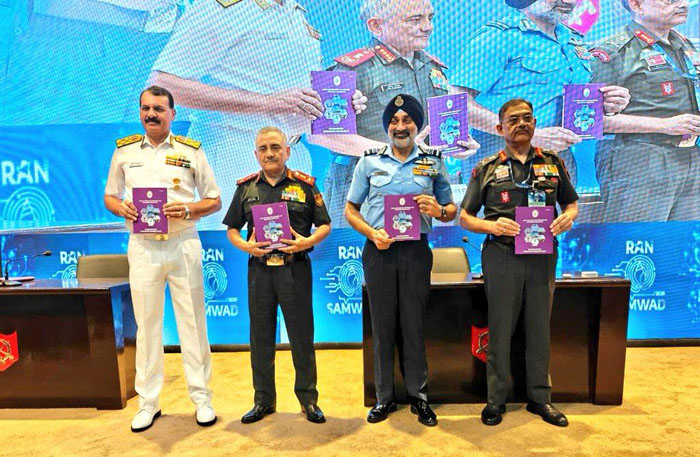

India is again at a point where its military reform risks mistaking optics for substance. The concept of integrated theatre commands (ITC) was recently discussed at an event organised at the Army War College saw differing views of the Chief of Defence Staff and the Service Chiefs to the fore. The debate on the need for ITC once again dominated the headlines, suggesting that the mere act of placing the Army, Navy and Air Force under unified geographic structures may not produce synergy and add teeth to the deterrence. The character of modern war is not about who controls which landmass, aerospace or maritime front on a map. It is about who can dominate the battlespace across multiple domains, compress decision cycles, and deliver precise effects faster than the adversary. India’s priority, therefore, should not be the hurried creation of theatre commands but the establishment of functional commands that integrate resources across services for specific operational effects. Cyber Command, Space Command, C5ISR Command, Cognitive Warfare Command, a Drone Corps, and a dedicated Air Defence Command will achieve more for India’s security in the coming decade than geographic theatre-isation.

India is again at a point where its military reform risks mistaking optics for substance. The concept of integrated theatre commands (ITC) was recently discussed at an event organised at the Army War College saw differing views of the Chief of Defence Staff and the Service Chiefs to the fore. The debate on the need for ITC once again dominated the headlines, suggesting that the mere act of placing the Army, Navy and Air Force under unified geographic structures may not produce synergy and add teeth to the deterrence. The character of modern war is not about who controls which landmass, aerospace or maritime front on a map. It is about who can dominate the battlespace across multiple domains, compress decision cycles, and deliver precise effects faster than the adversary. India’s priority, therefore, should not be the hurried creation of theatre commands but the establishment of functional commands that integrate resources across services for specific operational effects. Cyber Command, Space Command, C5ISR Command, Cognitive Warfare Command, a Drone Corps, and a dedicated Air Defence Command will achieve more for India’s security in the coming decade than geographic theatre-isation.

The seduction of theatre commands lies in its simplicity. One commander, one theatre, one fight. But India’s security environment is not the global expeditionary arena of the United States or the mass mobilisation template of China. It is defined by contested borders, hybrid conflict, proxy terrorism and the increasing convergence of cyber, space, and information with conventional operations. To assume that this complexity can be solved by reassigning formations under new headquarters is naive. India does not require a reorganisation of organisational charts; rather, it requires a revolution of the organisation in its integration of sensors, shooters and decision-makers. The acme of future dominance will be reducing the kill chain and closing technology gaps, and building agile structures to combat in a physical-cyberspace battlespace. This requires fusion of kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities in an integrated multidomain environment.

Operation Sindoor offered a glimpse of this future. But it was a low-end form of threat model, which must not be overplayed. Yet the operation succeeded because air power, cyber disruption and ground manoeuvre were synchronised in real time, not because of a new command headquarters. Yet it also revealed voids: gaps in drone swarms, deficiencies in electronic warfare coordination, delays in data fusion. These are not problems solved by appointing a theatre commander; they demand functional commands with the authority, resources and expertise to integrate capabilities across services. A Cyber Command must lead in offensive and defensive operations in the digital domain, denying adversaries the ability to cripple infrastructure or manipulate information. A Space Command must secure India’s satellites and exploit space-based ISR and communication to give forces decision superiority. A C5ISR Command must be the backbone, linking every radar, drone, satellite and sensor into a seamless picture for commanders. A Drone Corps must ensure India does not fight tomorrow’s wars with yesterday’s tools, creating swarms, kamikaze drones and loitering munitions at scale. A Cognitive Warfare Command must prepare India for the battles of perception, narrative and psychological influence where wars may be won or lost without a shot being fired. And an Air Defence Command must protect the nation’s skies across the entire geographical extent in an age where drones, missiles and hypersonic challenge every assumption of legacy defence systems and the geometry cum geography of warfare has transformed.

The obsession with theatre commands risks importing foreign models unsuited to India’s realities. America built its commands for wars fought thousands of miles from its homeland, enabled by unmatched logistics and technology. China’s system reflects its drive for continental dominance and its centralised political culture. India has neither the resources of the United States nor the authoritarian control of China. Its wars will be fought under nuclear shadow, with hostile neighbours exploiting hybrid and grey zone tactics. Its geography demands rapid redeployment of air and missile forces, not static geographic fiefdoms. Its political system demands reforms that are transparent, debated and sustainable, not cosmetic rearrangements to meet arbitrary deadlines. Functional commands tailored to India’s operational environment are, therefore, the logical and realistic path.

This shift also demands clarity in political intent. India has long operated without a written National Security Strategy, leaving the armed forces to interpret political objectives through ad hoc directives. Without such a foundation, theatre-isation risks becoming an end in itself rather than a means to national security. A clear strategy must set the hierarchy of threats and the sequence of capability development. Only then can functional commands be created with defined mandates and resources. The military must adapt to this political direction, not negotiate around it. Reform in a democracy is driven from the political level; the services must implement, even if it means shedding legacy comfort zones and single-service silos.

This shift also demands clarity in political intent. India has long operated without a written National Security Strategy, leaving the armed forces to interpret political objectives through ad hoc directives. Without such a foundation, theatre-isation risks becoming an end in itself rather than a means to national security. A clear strategy must set the hierarchy of threats and the sequence of capability development. Only then can functional commands be created with defined mandates and resources. The military must adapt to this political direction, not negotiate around it. Reform in a democracy is driven from the political level; the services must implement, even if it means shedding legacy comfort zones and single-service silos.

Functional commands also align better with the character of contemporary conflict. Drone warfare has already changed battlefield geometry in Ukraine, Nagorno-Karabakh and Gaza. Cognitive warfare has blurred the line between peace and conflict, with perception management and disinformation creating real strategic outcomes. Space has become the high ground, and cyber intrusions can paralyse a nation before its armed forces mobilise. In this environment, battles are no longer neatly divided into land, sea and air. They are fought in networks, in frequencies, in minds. It is functional integration across these domains that produces victory, not the reshuffling of geographic boundaries. Theatre commands may eventually have a role, but without functional pillars, they will be empty shells.

The Indian military culture must also change. For too long, planning has been dominated by attritionist thinking, single-service biases and preparation for the last war. Structural reform will fail if it does not address these cultural impediments. Professional military education must inculcate jointness, risk-taking and adaptability. Cross-service tenures must be incentivised. Command styles must evolve from centralised control to mission command, empowering leaders at the edge to exploit opportunities in fast-moving, technology-driven battles. Functional commands will force this cultural change by requiring officers from all three services to work together on specific domains rather than fight for turf under geographic umbrellas.

This is not to dismiss the logic of theatre commands altogether. Over the long term, once capabilities are built, functional commands stabilised, and a culture of jointness internalised, India may well benefit from geographic commands that unify resources for specific theatres. But sequencing matters. To build theatre commands first is to put the cart before the horse. India risks creating new bureaucratic layers that delay decisions, dilute accountability and confuse the chain of command at precisely the moment when wars demand clarity and speed. Functional commands, by contrast, create integration where it matters most—at the level of sensors, networks, weapons and effects.

Political leadership must therefore resist the temptation of symbolic announcements and instead drive a phased, capability-first approach. Parliament and Cabinet must mandate timelines for functional commands, allocate budgets for critical technology infusion, and ensure accountability in implementation. The Chief of Defence Staff should be empowered to overcome service silos and drive through military beneficial changes against the institutional resistance or political patronage. Civil-military dialogue needs to be institutionalised, such that strategy, capability and structure co-evolve. Reform cannot be left to inter-service bargaining; it must be a national project led by a National Security Strategy and pay off better at the cutting edge than exists today.

India has little time. China is investing in drone swarms, AI-enabled targeting and cognitive warfare. Pakistan continues to refine hybrid strategies of terror, cyber and propaganda. Both are learning from Ukraine and Gaza, where kill chains shrank to minutes and information dominance often mattered more than territorial control. If India waits, it risks falling further behind. If it rushes into theatre-isation without capability building, it risks creating hollow structures that crumble under pressure. The only path is deliberate, professionally driven, capability-first reform centred on functional commands that integrate the battlespace for effect.

It is imperative to integrate, but its priority should integrate minds, culture, technologies and effects and not just flags and formations. The priority, along with desired service capabilities, must be functional commands for multidomain integrated effects in the battlespace, dominate the kill chain and decision cycle through a Multi-Domain Command and Control (MDC2) Architecture. They will ensure that the foundation of theatre commands mature theatre is built on professionalism, not weakness or political expediency. Until then, India’s priority must be clear: better to integrate the battlespace through functional synergy than to chase the mirage of theatre-isation. In war, substance always defeats form and outcomes at the cutting edge matter most.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.

Lieutenant General A B Shivane, is the former Strike Corps Commander and Director General of Mechanised Forces. As a scholar warrior, he has authored over 200 publications on national security and matters defence, besides four books and is an internationally renowned keynote speaker. The General was a Consultant to the Ministry of Defence (Ordnance Factory Board) post-superannuation. He was the Distinguished Fellow and held COAS Chair of Excellence at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies 2021 2022. He is also the Senior Advisor Board Member to several organisations and Think Tanks.