Road infrastructure is often called the backbone of the economy – and for good reason. In fact Infrastructure and Economy are interdependent and complementary and contribute towards creating potent Comprehensive National Power in a big way. A robust highway network enables efficient movement of goods and people, spurring trade, connectivity, and growth. In India, National Highways (NHs) carry 40% of total traffic. Recognizing this, the government has earmarked Rs 2.72 lakh crore for capital budget for NHs in FY 2025-26. Such spending is part of a long-term strategy to boost economic growth.

The Progress

The NH network has grown fast during past decade to be the second largest road network globally. Government spending on road infrastructure has increased 6.4 times during last 10 years, with a 57% rise in budget allocation. During past three years, projects covering an average of 6000 km are being awarded annually. There are plans to bid out 124 highway projects worth Rs 3.4 lakh crore in FY 26, covering 6,376 km.

The Union Minister has pushed many constructive and positive changes to accelerate the progress of highways which has resulted in huge direct, indirect and induced employment across various sectors. There has been major initiative to develop 700 Wayside Amenities by 2028-29, providing clean restrooms, quality food, rest areas, fuel stations and EV charging points. Under Minister’s vision for safe roads, 14,000 accident-prone black-spots have been rectified. However, infrastructure’s true value is realized not just by spending more, but by building better. Recent years have underscored the critical importance of quality infrastructure. When key road and bridge links collapse or wash out during floods, it doesn’t only endanger lives; it also disrupts supply chains, hurts commerce, and imposes huge recovery costs.

The Union Minister has pushed many constructive and positive changes to accelerate the progress of highways which has resulted in huge direct, indirect and induced employment across various sectors. There has been major initiative to develop 700 Wayside Amenities by 2028-29, providing clean restrooms, quality food, rest areas, fuel stations and EV charging points. Under Minister’s vision for safe roads, 14,000 accident-prone black-spots have been rectified. However, infrastructure’s true value is realized not just by spending more, but by building better. Recent years have underscored the critical importance of quality infrastructure. When key road and bridge links collapse or wash out during floods, it doesn’t only endanger lives; it also disrupts supply chains, hurts commerce, and imposes huge recovery costs.

The Pitfalls

Despite being one of the most capital-intensive sectors and a key enabler of economic growth, the National Highway infrastructure in India is plagued by systemic inefficiencies, institutional weaknesses, and quality concerns. Recent structural collapses, chronic potholes, stalled projects, and spiralling costs are not isolated incidents—they are symptoms of deeper, structural maladies.

Union Minister for Road Transport and Highways expressed his deep anguish in a virtual gathering during the inauguration of National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) building at Dwarka which took about nine years to complete and saw eight NHAI chairmen and two governments. He was unhappy over a ‘delayed’ work culture in NHAI and said it was time to show exit door to ‘non-preforming assets’ complicating and delaying projects by creating obstacles. The NHAI has become a breeding ground for inefficient officials who are creating hurdles and referring every matter to committees and it was time to ‘suspend’ and ‘terminate’ them and bring in reforms in its functioning.

NHAI has a mix of permanent cadre, officials on deputation and contractual staff in the ratio of approximately 30%, 30% and 40% respectively, which creates lack of continuity, gaps in Institutional memory, poor organisational ethos and lack of accountability. All these weaknesses have given rise to gross inefficient work culture and deep rooted corrupt practices. The following key problem areas outline the true scale and complexity of the crisis.

- Illusory Expansion and Misreported Progress. While official statistics portray a massive expansion of India’s NH network over the past decade, a closer examination reveals that this growth is, in part, statistical rather than structural. Between 2014 and 2023, the total length of NHs reportedly grew by 60%, from approximately 91,300 km to 1.45 lakh km. However, a significant share of this expansion—about 50,000 km—came not from new construction, but from the reclassification of existing state highways and roads into the NH network.

- Shift from Linear Kilometers to Lane Kilometers. In 2018, the Ministry adopted a new reporting metric: lane-kilometer construction, replacing the conventional linear kilometer count. For example, building 1 km of a four-lane road is reported as 4 lane-km. By this measure, India “constructed” 34,378 km of highways in 2017–18, compared to just 9,829 km under the earlier linear system.

- The Core Problem: Substance vs Symbolism – The rebranding of old roads and the adoption of lane-kilometer metrics point to a larger issue of optics over outcomes.

-

- These practices project an illusion of rapid growth, often cited in government achievements, but mask operational and structural deficiencies.

- This misrepresentation undermines accountability, misinforms policy debates, and leaves pressing ground-level problems—such as potholes, unfinished stretches, and inadequate safety features—unaddressed.

- Chronic Project Delays. The most persistent and damaging flaw in India’s highway development is the widespread delay in project execution, which directly translates into massive cost overruns, legal disputes, and lost public trust. The challenge isn’t just to build highways—it is to build them on time, within budget, and to lasting quality standards. According to data from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI):

-

- As of early 2024, over 40% of major central infrastructure projects were running behind schedule.

- Out of 1,873 monitored central projects, 779 were delayed, with an average delay of 36 months.

- Such prolonged lags postpone public benefits, undermine return on investment, and cause cascading disruptions in logistics, regional development, and national connectivity plans.

- Massive Financial Impact

-

- As of March 2024, 449 large projects (each over Rs 150 crore) had incurred Rs 5.01 lakh crore in cost overruns—an increase of nearly 19% over their originally sanctioned estimates.

- These overruns reflect wasted opportunity cost—funds that could have been used to build new roads, hospitals, schools, or rail networks.

- Even assuming a conservative corruption/leakage rate of 20%, this means Rs 1.0 lakh crore may be lost outright to inefficiencies or malfeasance which is a huge wasteful loss.

- Over-Centralization of Decision Making. Too many approvals are routed through Regional Officers (ROs), Project Directors (PDs), and Ministry Headquarters. This not only slows work but demotivates site-level teams who are best placed to make real-time decisions.

- Real-World Impact on the Public and Economy. Incomplete highways that were meant to reduce congestion, improve logistics, and save fuel remain inaccessible, thereby denying users the intended benefits of time and cost efficiency. Meanwhile, commuters and freight operators are forced to navigate half-finished stretches, poorly designed detours, and roads lacking basic amenities. On a macroeconomic level, the delay in project execution triggers inflation-linked cost escalation—with rising prices of construction materials, land, and interest rates further worsening the financial viability of projects.

- Tender Manipulation: The First Breach in the System. The genesis of corruption in highway infrastructure often lies in non-transparent and manipulated tendering processes, which distort competition and compromise value-for-money outcomes. In many cases, tender conditions are deliberately customized to favour select firms—either due to political pressure or through illicit inducements to officials. The consequences are two-fold: either abnormally low bids are accepted, resulting in post-award quality compromises and dispute claims, or artificially inflated project estimates are pushed through—justified by unnecessary design complexity or padded scope—leading to massive cost overruns.

- The L1 Bidding Fallacy: Cheap Wins, Costly Consequences. A key structural flaw in highway procurement is the uncritical adoption of the Lowest Bidder (L1) system. In many instances, bids that are 40–50% below the estimated cost are accepted in a rush to expedite award decisions. To recover their margins, many rely on post-award tactics such as inflated claims, time extensions, and arbitration—effectively turning the project into a legal and financial trap for the government.

- Contractor Inefficiencies and Lax Monitoring. Despite significant investment in the NH sector, execution at the ground level continues to suffer due to poor contractor performance and weak field-level oversight. The contractor’s inefficiencies, coupled with inadequate supervision, delay project completion, degrade quality, and inflate costs.

- Delayed Mobilization Post-Award. A persistent inefficiency plaguing highway execution is the habitual delay in mobilization by contractors even after issuance of Letters of Award (LoAs). Despite formal award of work, contractors frequently cite resource constraints—such as unavailability of labour, machinery, or site readiness—as justifications for inaction.

- Collusive Extension Of Time (EOT) Culture. A subtler but highly damaging form of inefficiency stems from deliberate, engineered delays by contractors, who later seek EOTs under the pretext of factors such as bad weather, non-availability of quarries or statutory clearances, and lack of scope clarity. This practice, often termed “soft corruption,” enables contractors to regularize schedule slippages on paper, circumventing penalties and creating a false narrative of procedural compliance.

- The Triangular Nexus: Authority, Engineer and Contractor The highway execution model was originally structured around a three-tier system—Authority, Engineer, and Contractor—to ensure checks and balances, with each entity expected to independently uphold project integrity. However, in practice, this framework often degrades into a two-party collusion between the Engineer and the Contractor, effectively neutralizing the oversight role of the Authority. This creates a mutual benefit loop, wherein engineers gain personal favours or illicit financial incentives, contractors receive certified bills and generous time extension, and the authority either remains complicit or chooses inaction.

- The Economic Impact of Corruption: 20–30% Value Drain Corruption in infrastructure projects is not merely a moral concern—it is a quantifiable economic burden with significant fiscal implications. Global benchmarks and Indian audit observations estimate that 20–30% of project value is routinely lost to corruption in environments lacking robust institutional safeguards. These losses are not abstract—they materialize in gold-plated projects with inflated costs, redundant and unjustified scope changes, artificial cost escalations, and frequent repair cycles for newly commissioned assets.

- The Double Burden: Maintenance and Reconstruction Costs The systemic failure in construction quality has forced the government into a wasteful and unsustainable cycle of repeated spending. Between 2021 and 2024, the government spent Rs 17,900 crore on highway maintenance alone—averaging Rs 6,000 crore per year—with a sharp increase to Rs 9,599 crore budgeted for FY 2024–25, indicating a deteriorating national road health profile. This self-perpetuating loop of build–neglect–repair–rebuild has been aptly described by experts as an “extortionary phenomenon”, where the taxpayer pays multiple times for the same road.

- Poor Payment Transparency and Physical Coercion. The absence of automated, transparent billing and payment systems in highway project execution has created significant vulnerabilities to corruption and coercion. Manual verification of bills, coupled with a lack of real-time digital payment mechanisms, opens the door to bribery for file movement, unjustified delays, and the absence of a verifiable audit trail for contractor payments. One example to emulate is the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), which reportedly managed to reduce corruption to near-zero by streamlining processes – they achieved 90% bill payments within 9 days and earned Gold Certificate for two consecutive years by Ministry of Commerce, for bringing in this revolutionary change for transparent and efficient system.

- Misaligned Metrics: Spend Over Outcome A fundamental flaw in the monitoring of highway projects lies in the over-reliance on financial expenditure milestones as a proxy for progress, rather than on actual physical or quality-based achievements. In many cases, projects are prematurely declared “50% complete” simply because 50% of the allocated funds have been disbursed, even when only 20–30% of the physical work is complete on site. This misalignment creates perverse incentives—where the emphasis shifts from delivering quality infrastructure to spending allocated budgets quickly.

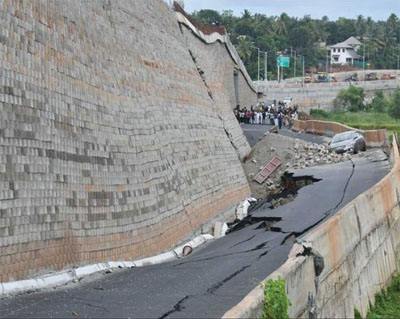

- Safety Consequences of Corruption. The consequences of corruption in highway infrastructure go well beyond financial loss—they pose a direct threat to public safety and structural integrity. The frequent collapse of bridges, flyovers, and water-logged highways are not accidents—they are the structural manifestations of compromised execution, unchecked malpractices, and diluted accountability.

- Poor Quality Construction and the Maintenance Burden. The frequent collapse of newly built infrastructure, proliferation of potholes, and ever-increasing repair budgets underscore that we are building fast—but not building to last. The consequences are not only fiscal but also fatal. The burden of poor construction is borne by both the economy and the citizen—through inflated budgets, hazardous roads, and repeated repairs. This is not just a construction failure—it is a failure of governance, enforcement, and ethics.

- Lax Enforcement and Absence of Accountability.

-

- Contractors routinely escape penalties due to expiry of liability periods before defects surface.

- Authority Engineers (AEs) rarely face consequences even when quality lapses occur under their watch.

- Whistle-blowers or users have no formal channel to report defects, further shielding malpractices.

- The Bigger Picture: Public Safety, Not Just Infrastructure. The consequences of poor-quality infrastructure extend far beyond cracked pavements and delayed timelines—they are measured in lives lost, injuries suffered, and livelihoods disrupted. The economic fallout is equally severe: logistics slow down, fuel consumption rises, and supply chains are disrupted as trucks crawl over damaged corridors. In essence, every poorly built road is not just a wasted investment—it is a systemic failure that weakens national productivity, regional mobility, and public morale.

- Legal Disputes, Arbitration, and Institutionalized Inefficiency. Amidst the challenges of physical execution and financial mismanagement in India’s highway infrastructure sector, one of the most financially debilitating yet under-addressed issues is the proliferation of contractual disputes and arbitration claims. As of March 2025, the NHAI is embroiled in arbitration claims amounting to Rs 1.0 lakh crore, representing nearly 40% of NHAI’s total liabilities. This amounts to approximately 40% of its capital expenditure budget. This figure, growing year-on-year, ties up substantial fiscal bandwidth and undermines NHAI’s capacity to initiate or sustain new projects.

- Case in Point: The Dwarka Expressway Embarrassment. One of the most striking examples of cost inflation and questionable project justification in recent years is the Dwarka Expressway project. Originally approved by Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs at Rs 18.2 crore per kilometer, the final project cost burgeoned to over Rs 250.77 crore per kilometer—a 14-fold escalation. The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) flagged the costs as “very high”. In public discourse, the project came to be dubbed “Sone ki Sadak” (Golden Road)—a powerful metaphor for perceived government indulgence, inefficiency, or collusion.

- The Pothole Pandemic: A National Shame. Potholes have become a defining symbol of India’s infrastructure decay, especially during the monsoon season, when roads across the country deteriorate into cratered surfaces often likened to the moon’s landscape. At the national level, data presented in Parliament reveals that potholes are responsible for over 4,000 road accidents annually, resulting in hundreds of deaths—making them one of the most preventable yet persistently ignored causes of road fatalities.

Recommendations : Building Better Roads in Amrit Kaal

To address these multifaceted issues, a multi-pronged reform agenda is needed. The aim must be to inject greater transparency, efficiency and accountability at every stage – from planning and procurement to execution, maintenance, and oversight. Below are key recommendations and reform strategies that government stakeholders (from MoRTH and NHAI to state agencies and oversight bodies) should pursue to put India’s highway development on a better track.

- Decentralize and Streamline Decision-Making. Delegating appropriate financial powers to PDs and ROs can speed up execution, as long as their decisions are logged in the system for audit. A balanced approach is needed to cut redundant hierarchy but increase accountability through real-time oversight. In fact, there is a compelling need to bring in immediate cadre reforms in NHAI.

- Strict Procurement and Tendering Reforms. The contracting process must be reformed to prevent both corruption and future disputes. The practice of accepting abnormally low bids should be curtailed. This prevents the “suicide bidding” that often leads to poor work or cost escalation claims later. A fair and efficient dispute resolution clause is also critical.

- Evolving Qualification Norms. The current Indian system, largely driven by L1 (lowest bidder) criteria, needs to evolve into a value-based, quality-centric procurement regime. We must build a centralized digital contractor evaluation portal linked to MORTH/NHAI/CPWD projects. Performance scoring post every project (timeliness, quality, safety, client satisfaction) should be mandatory. We should include only CPARS (Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System)-qualified contractors in select tenders, especially for high-value expressways or BOT projects.

- Institutionalizing Incentives: Reward-Based Contracting. A robust mechanism to incentivize timely or early completion must be institutionalized within all EPC/PPP contracts. Such a framework will:

-

- Motivate contractors to plan better, mobilize faster, and work efficiently.

- Decongest arbitration pipelines, as projects completed ahead of schedule rarely enter disputes.

- Reduce interest burden and escalations by compressing the overall project cycle.

- Independent Audits and Oversight. Robust oversight is vital to keep the system honest. Importantly, audit findings and action taken should be made public. Transparency is a disinfectant: when audit results, project statuses, and contractual deviations are published openly, there is pressure on officials and contractors to avoid wrongdoing.

- Focus on Maintenance and Asset Management. There is a tendency to emphasize new highway construction while neglecting maintenance of existing assets. This must change. Given budget constraints, asset monetization is a useful strategy: NHAI can raise funds by leasing out completed highways to private investors (through Toll-Operate-Transfer or Infrastructure Investment Trusts), and plough back that money into maintaining other roads.

- Accountability for Contractors and Engineers. Reforms must ensure that those who build and supervise our highways are strictly accountable for their performance. Contractors who consistently deliver quality work on time should be rated well and earn faster security deposit releases or preference in bidding. On the other hand, non-performers must face tangible consequences. Furthermore, the government must introduce a rigorous rating system for Authority Engineers and Consultants.

- Arbitration Reforms. To course-correct, India needs urgent and systemic reforms, including:

-

- A completely independent arbitration pool, with conflict-of-interest-free empanelment.

- Amendments to the Arbitration Act to allow scrutiny of arbitrator misconduct.

- Mandatory use and empowerment of DRBs and CCIEs.

- Linking officer appraisals and financial accountability to arbitration outcomes.

- Strengthening government legal teams, with dedicated legal officers for each major project.

- Real-time third-party audits and digital documentation of project progress to build defensible positions.

- Legal and Policy Measures to Deter Corruption. Fast-track courts for corruption cases (especially involving large public works) could help ensure timely justice – delayed trials only embolden wrongdoers. The government should also empower bodies like the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC), State Vigilance Bureaus, and Lokayuktas to proactively investigate highway project complaints. Leveraging technology, all project payments and transactions should be traceable online to reduce scope for under-the-table deals. Ultimately, an ethical environment has to be cultivated from the top down, with leadership in MoRTH and NHAI making it clear that integrity is non-negotiable.

- Digital Transparency & Workflow Monitoring: Embrace e-governance tools to make processes transparent and minimize human discretion. Project Management Software to be used to track all project data and file movements, and use analytics to forecast delays and disputes, issuing early warnings. Similarly, important project milestones should be geo-tagged and photo/video documented to deter false reporting.

- Digital Twins & AI-Based Central Monitoring. To address the rampant information asymmetry and fake reporting in highway construction, Digital Twin Technology should be mandatorily deployed in all projects exceeding Rs 100 crore. It will enable predictive maintenance and lifecycle optimization, reducing total cost of ownership. Live dashboards can be opened to CAG, MoRTH, Parliament Committees, and even public observers for critical corridors.

- Enabling Citizen Engagement. Encouraging citizens and honest insiders to report malpractices can greatly enhance oversight. Going forward, highway users should be empowered via grievance portals and apps to report issues like poor maintenance, contractor malpractices, or toll irregularities, with assurance of prompt action. All the project information should be put on open website and be continually updated – including project progress dashboards, contract awards, and quality ratings of contractors/consultants. In sum, transparency, citizen engagement, and social accountability will ensure that the whole system stays honest and oriented towards the public good.

Conclusion: Driving Reforms to Restore Trust

India stands at the crossroads with respect to its infrastructure development. On one hand, never before have resources and political will been so firmly behind building world-class highways. On the other hand, the spate of recent road collapses, pothole embarrassments, and audit revelations have shaken public confidence. It is evident that business-as-usual will not suffice – pouring more money is not a solution unless it is accompanied by deep-seated governance reforms. When bridges fail and roads crumble soon after inauguration, it is not merely an engineering failure but a failure of ethics and oversight. Each such incident erodes the people’s trust in the system and tragically, sometimes their lives. We cannot afford to continue on this path. As the Prime Minister himself has emphasized, the focus now has to shift not just to expanding the highway network, but widening and maintaining it to the highest standards. With greater transparency, stricter accountability, and active public vigilance, the cycle of waste and corruption can be broken. The road ahead during Amrit Kaal to 2047, can indeed be smooth – if we collectively choose not to be corrupt, and instead, to be accountable. The recommendations above provide a blueprint for change. Implementing them will not be easy; it requires breaking the status quo of entrenched interests and overcoming bureaucratic inertia.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, former DG Border Roads, doubled the pace of work to meet stringent targets post Galwan clash and worked to get an incremental budget allocation of 160% for GS roads during his tenure. He infused at least 18 new technologies to enhance speed and quality of projects. He brought transparency in expenditure through increased use of GeM and ensured timely payments to the firms for which BRO was awarded Gold Certificate for two consecutive years. He also ensured desired dignity, social security and visibility to the unsung BRO Karmyogis.

Lt Gen Rajeev Chaudhry, former DG Border Roads, doubled the pace of work to meet stringent targets post Galwan clash and worked to get an incremental budget allocation of 160% for GS roads during his tenure. He infused at least 18 new technologies to enhance speed and quality of projects. He brought transparency in expenditure through increased use of GeM and ensured timely payments to the firms for which BRO was awarded Gold Certificate for two consecutive years. He also ensured desired dignity, social security and visibility to the unsung BRO Karmyogis.