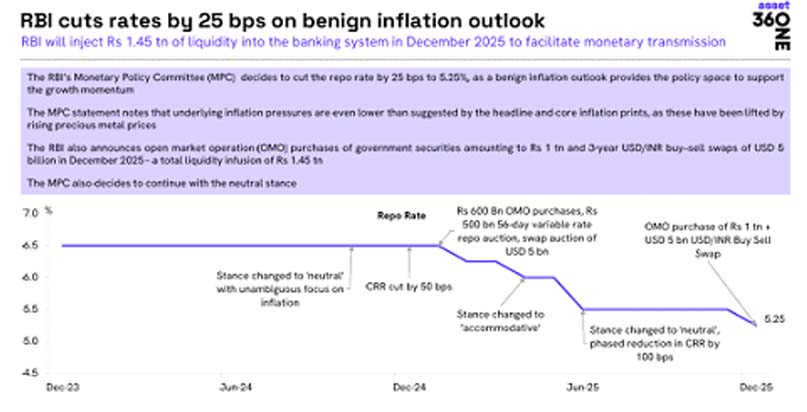

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), in line with broad market expectations, reduced the Repo rate by 25 basis points (bps) (from 5.50% to 5.25%) while retaining a Neutral policy stance.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) reduced the Repo rate by 125 bps cumulatively in four meetings this year, starting in February. In its October Policy, the MPC kept the Repo rate unchanged at 5.50% and maintained the policy stance as neutral.

The RBI also announced the purchase of ₹1 lakh crore of government securities via OMO and a three-year US$5 billion buy/sell swap, intended to stabilise money markets, ease financial conditions, and support the rupee. These liquidity injection measures collectively mark a calibrated, not aggressive, easing phase, where the RBI seeks to nurture growth without undermining macroeconomic stability or reigniting inflationary pressures.

Overview of Repo Rate Trends (2010–2025)

The key repo rate changes over the 15 years are given below: .

| Effective Date | Repo Rate | % Change |

|---|---|---|

| 19 March 2010 | 5.00% | +0.25% |

| 20 April 2010 | 5.25% | +0.25% |

| 2 July 2010 | 5.50% | +0.25% |

| 27 July 2010 | 5.75% | +0.25% |

| 16 September 2010 | 6.00% | +0.25% |

| 2 November 2010 | 6.25% | +0.25% |

| 25 January 2011 | 6.50% | +0.25% |

| 17 March 2011 | 6.75% | +0.25% |

| 3 May 2013 | 7.25% | +0.50% |

| 20 September 2013 | 7.50% | +0.25% |

| 29 October 2013 | 7.75% | +0.25% |

| 28 January 2014 | 8.00% | +0.25% |

| 15 January 2015 | 7.75% | -0.25% |

| 4 March 2015 | 7.50% | -0.25% |

| 2 June 2015 | 7.25% | -0.25% |

| 29 September 2015 | 6.75% | -0.50% |

| 5 April 2016 | 6.50% | -0.25% |

| 4 October 2016 | 6.25% | -0.25% |

| 2 August 2017 | 6.00% | -0.25% |

| 6 June 2018 | 6.25% | +0.25% |

| 1 August 2018 | 6.50% | +0.25% |

| 7 February 2019 | 6.25% | -0.25% |

| 4 April 2019 | 6.00% | -0.25% |

| 6 June 2019 | 5.75% | -0.25% |

| 7 August 2019 | 5.40% | -0.35% |

| 6 February 2020 | 5.15% | -0.25% |

| 27 March 2020 | 4.40% | -0.75% |

| 22 May 2020 | 4.00% | -0.40% |

| 6 August 2020 | 4.00% | 0.00% |

| 9 October 2020 | 4.00% | 0.00% |

| May 2022 | 4.40% | +0.40% |

| 8 June 2022 | 4.90% | +0.50% |

| 5 August 2022 | 5.40% | +0.50% |

| 30 September 2022 | 5.90% | +0.50% |

| 7 December 2022 | 6.25% | +0.35% |

| 8 February 2023 | 6.50% | +0.25% |

| 8 June 2023 | 6.50% | 0.00% |

| 18 September 2024 | 6.50% | 0.00% |

| 6 December 2024 | 6.50% | 0.00% |

| 7 February 2025 | 6.25% | -0.25% |

| 9 April 2025 | 6.00% | -0.25% |

| 6 June 2025 | 5.50% | -0.50% |

| 6 August 2025 | 5.50% | 0.00% |

Global Cues

The global economic environment remains decidedly fragile, marked by moderating growth, uneven disinflation, and heightened geopolitical risks. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook (October 2025) projected global growth marginally over 3% with advanced economies (AEs) expanding slowly and emerging markets doing better on average, but with downside risks stemming from geopolitics, trade restrictions and financial volatility. The OECD’s latest projections envisage that the world output is expected to decelerate from 3.2% in 2025 to 2.9% in 2026, reflecting the lagged impact of the most aggressive monetary tightening cycle in decades. Although inflation is gradually moving closer to Central Bank targets across major advanced and emerging economies, the path to price stability remains bumpy, with services inflation still sticky and wage dynamics yet to fully normalise.

Fiscal vulnerabilities are re-emerging as a critical global concern. Government debt ratios across both advanced and emerging economies remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels, constraining fiscal space and increasing the urgency of consolidation. Ageing populations are raising pension and healthcare costs, while geopolitical fragmentation is driving higher defence spending. Simultaneously, the mounting financial requirements for climate mitigation and resilience exacerbate long-term structural pressures. This unsavoury combination of elevated debt and rising multiyear expenditure commitments is straining sovereign balance sheets and narrowing policy flexibility. Not a pretty picture, is it?

Risks to the global outlook remain tilted to the downside. Labour markets, while still broadly resilient, are showing signs of cooling as vacancy-to-unemployment ratios decline and hiring momentum weakens. Financial markets face the possibility of abrupt repricing if the current wave of enthusiasm surrounding artificial intelligence fails to translate into sustained earnings growth.

Tariff Imbroglio

Significantly escalated protectionist trade policy has immediate and long-term consequences for the global economy in general and emerging market economies (EMEs) in particular. As Adam Smith wrote presciently in his classic work An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations (Book IV, Chapter 2) (published March 9, 1776): “The very bad policy of one country may thus render it in some measure dangerous and imprudent to establish what would otherwise be the best policy in another”.

Further, geopolitical tensions ranging from US–China strategic rivalry and trade restrictions on critical technologies to disruptions in key shipping lanes could disrupt supply chains and undermine trade flows. Intensifying regional conflicts or commodity-price shocks could further complicate the disinflation process. These far-reaching dynamics hampered global rebound and raised worrisome concerns of mounting global debt, risks to financial stability and a resilient financial system.

Overall, the global economy is characterised by slower but more volatile growth, with policymakers required to navigate a narrow path between maintaining financial stability, achieving price stability, and ensuring sustainable public finances.

Macroeconomic Setting: The Lexicon of Change

1. Disconcerting Disinflation Trend-Discordance and Dissonance

Many analysts had suggested a continued pause despite the remarkable 0.25% CPI inflation print for October 2025, the lowest since the CPI series began in 2013. Their caution stemmed from base-effect-driven volatility in food inflation, persisting risks from vegetables, pulses, cereals, climate-linked uncertainty (El Niño/La Niña transitions), and inflation expectations that had softened but not decisively anchored. The RBI has repeatedly emphasised the need for sustained, broad-based disinflation, not transient declines. Thus, one monthly print alone could not have justified easing.

2. Strong Grammar of Growth-“Never lose the sight of a forest just for a tree.”

In this disconcerting overarching global environment, what carried the day was the broad-based revival in growth with Q2 FY26 GDP surging to ~8.2%, a six-quarter high; robust domestic demand, services-sector momentum, and accelerating capex; and improved corporate profitability and healthy tax collections. This constellation of factors created policy space where a modest rate cut could support the recovery without jeopardising price stability.

The RBI raised its GDP growth forecast for FY2026 to 7.3% from the previous 6.8%. The quarterly estimates are Third Quarter FY2026: 7%, up from 6.4%; Fourth Quarter FY2026: 6.5%, up from 6.2%; First Quarter FY2027: 6.7%, up from 6.4%; and Second Quarter FY2027: 6.8%.

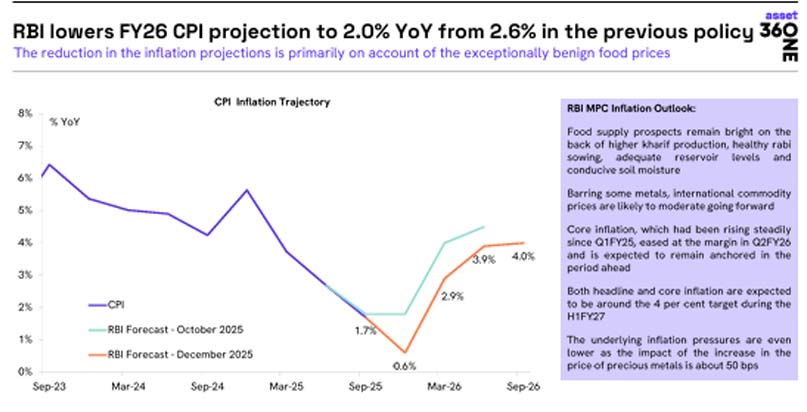

3. Unusually Low Inflation

The October CPI print, supported by food-price easing and outright deflation in some categories, GST rationalisation, and favourable base effects, pushed headline inflation far below the target band.

The quarterly projections are Third Quarter FY2026: Reduced from 1.8% to 0.6%; Fourth quarter fiscal year 2026: Reduced from 4% to 2.9%; First quarter fiscal year 2027: Reduced from 4.5% to 3.9%; and Second quarter fiscal year 2027: Forecast 4%.

Despite caution on food-price volatility, the prevailing combination of low inflation and robust activity offered an opportune, low-risk window for monetary easing.

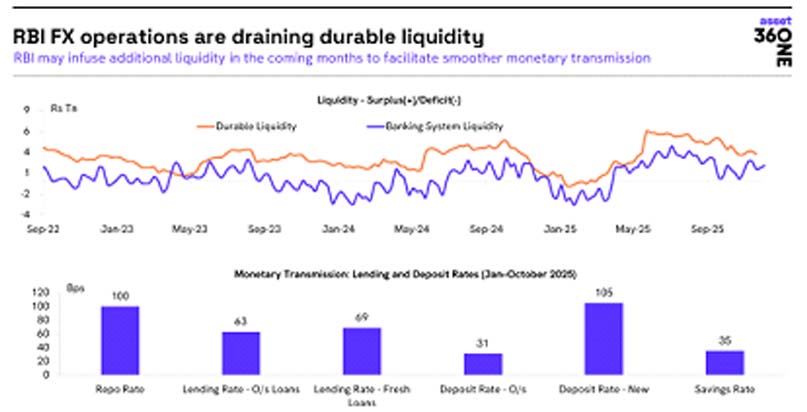

4. Rising Liquidity Tightness and Rupee Pressures

Liquidity had tightened significantly because of large government cash balances, festival-season currency leakage, and reduced forex inflows. Simultaneously, the rupee breached the ₹90 per US dollar mark, raising concerns about external financing costs, capital-flow dynamics, corporate external-borrowing stress, and imported inflation risks (especially via oil). The RBI, therefore, combined the rate cut with strong liquidity support, signalling that currency stability and market conditions were integral to the decision matrix.

With the Indian economy gaining steam and gross non-performing assets (GNPAs) ratio steeply declining to dropping to 2.6% of total advances in September 2024 (the NNPA-net non-performing assets ratio stood at approximately 0.6%), marking the lowest level in the past 12 years, according to the RBI’s latest Financial Stability Report. Accordingly, bank credit is expected to grow rapidly.

5. The “Goldilocks” Window- Looking at the Larger Picture

Given global cues and the domestic economic setting, the RBI found that the confluence of high growth, exceptionally low inflation, currency pressures, and tight liquidity created a rare “Goldilocks” moment, where the downside risks of easing were limited. The potential benefits of growth reinforcement, liquidity normalisation, and currency stabilisation were, however, substantial, inducing the RBI to move with the rate cut.

Development Discourse: Growth Up, Inflation Down

In its forward guidance, the RBI raised projections of GDP growth for FY26 to ~7.3% and lowered CPI inflation to ~2%. These revisions reflect confidence in strong real-economy momentum, benign inflation trajectory, supply-side cushioning from improved agricultural output and lower global commodity prices. However, the RBI highlighted that risks are asymmetrically tilted with food inflation remaining a structural vulnerability, oil prices and global commodity cycles remaining unpredictable, and the possibility of global monetary policy path (especially the US Fed) altering capital flows. This is why the policy stance remained Neutral, keeping future options open.

Broader Macroeconomic Impact and Implications

1. Liquidity Management and Monetary Transmission

Monetary policy transmission is the entire process starting from the change in the policy rate (Repo rate) by the central bank to various money market rates (e.g., inter-bank lending rates to bank deposit rates, bank lending rates) to households and firms, to government and corporate bond yields and asset prices (stock prices and house prices). It is expected to result in stable inflation and economic growth.

The 25-bps cut will gradually reduce retail and corporate borrowing costs, particularly home, auto, and consumer loans, MSME working capital requirements, and corporate term loans and refinancing of existing debt. But my long experience in a leading commercial bank suggests that the degree of transmission depends on banks’ deposit-cost pressures, liquidity conditions, and competitive dynamics in the lending market. Lower interest rates should bolster consumption, stimulate credit demand, and enhance the viability of capital-intensive and long-gestation projects, reinforcing the capex upcycle visible in H1 FY26.

2. Financial Markets and Liquidity

The ₹1 lakh crore OMO and $5 billion swap are likely to ease money-market strains, compress bond yields across the curve, support equity valuations, reduce rollover risks for corporates with forex liabilities, and cushion the rupee by supplying dollar liquidity. These measures strengthen confidence in the RBI’s willingness to stabilise financial conditions proactively.

3. Savers vs Borrowers: A Distributional Impact

While borrowers stand to benefit, deposit rates may soften, potentially hurting retirees, households dependent on interest income, and risk-averse savers. Balancing these distributional effects is an inherent challenge in any easing cycle.

4. Key Risks and Uncertainties – “For Whom the Bell Tolls?” (Ernest Hemingway)

Despite favourable macro settings, the risks of sticky food inflation due to supply shocks, oil price spikes amid global geopolitical tensions, currency volatility if global risk sentiment weakens, high deposit competition, which could delay transmission, and asset-price inflation in equities or real estate if liquidity becomes excessive persist. These risks justify the RBI’s eternal inflationary vigil.

Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy Synergies

Fiscal policy in 2025 has been mildly expansionary in parts: tax cuts and selective incentives to sustain consumption and investment were introduced earlier in the year and have supported activity and headline demand. The combination of fiscal loosening and lower inflation creates mixed implications for the RBI. Stronger fiscal support can stimulate growth and justify a more accommodative monetary stance to support the private sector. But if fiscal impulses materially widen the deficit or lead to “crowding out”, monetary policy may need to resist undue loosening or rely on operational tools to sterilise excess flows.

The composition and timing of fiscal measures is important. Temporary, well-targeted tax cuts that boost consumption during festival seasons may not be inflationary in the medium term, but enduring fiscal loosening would enhance demand pressures when global commodity prices pick up. With constrained fiscal space post the recent tax cuts and uncertain external environment, the heavy lifting must occur through Monetary Policy. The MPC will, therefore, incorporate fiscal projections and Centre/state budgets into its medium-term inflation outlook and assess whether the current low CPI is compatible with sustainable fiscal expansion. The RBI’s November commentary noted that recent fiscal and monetary measures were expected to bolster investment and growth, and this interplay was central to December’s policy calculus.

Calibrated Policy in a Virtuous Cycle

This Policy reflects a measured, risk-balanced approach. The rate cut provides incremental growth support, the liquidity operations address currency and money-market pressures, the Neutral stance signals caution amid global uncertainty, the projections reveal confidence in short-term macro stability, and the emphasis on liquidity management underscores that India’s monetary framework is now as much about financial-market functioning as about interest rates. The Policy is thus supportive but vigilant, avoiding any perception of an unrestrained easing cycle. There must be swifter monetary transmission and lower credit costs.

Conclusion: Straddling the Growth-Inflation Trade-off

The RBI’s December 2025 Monetary Policy astutely balanced monetary easing and liquidity support, reflecting a pragmatic response to an unusual macroeconomic configuration of strong growth, exceptionally low inflation, and rising external-sector vulnerabilities. A close look at the macroeconomic structure and momentum shows that the Policy delivers a modest lift to growth, helps steady liquidity and the rupee, takes advantage of a rare low-inflation window, and upholds prudence amid global uncertainties. Should growth begin to overheat, inflation pick up again, or global financial conditions tighten abruptly, the RBI has ample room to recalibrate. Conversely, if disinflation continues and growth starts to soften, scope remains for further calibrated easing.

As I have repeatedly emphasised, the RBI responds to the shifting growth–inflation balance. In this context, it has deftly steered a challenging macroeconomic moment, seeking to secure India’s growth path while preserving stability across inflation, financial markets, and the exchange rate.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.

Dr. Manoranjan Sharma, Chief Economist, Infomerics Ratings is a globally acclaimed scholar. With a brilliant academic record, he has over 350 publications and six books. His views have been published in Associated Press, New York; Dow Jones, New York; International Herald Tribune, New York; Wall Street Journal, New York.