In a landmark judgement, the Supreme Court has ruled that access to footpaths without obstruction is a citizen’s fundamental right, guaranteed by the Constitution under Article 21. It has instructed state governments and UTs to ensure encroachment-free pavements and inclusive city infrastructure, focused on the elderly and the differently-abled. This judgement has brought to the fore the sad state of public infrastructure across Indian cities, which actively excludes non-motorised movement in general and pedestrian movement in particular. Can we get our act together after the apex court’s scathing remarks?

If you are a driving enthusiast or someone who travels frequently, especially on new expressways and highways, you must have experienced that our roads have undergone a most profound transformation. Swanky four-lane access-controlled expressways and highways now connect more cities, and many more such new-age infrastructure projects are underway. These projects are poised to change the way we commute between cities. India’s road network has increased by over 60% between 2014 and 2024, highlighting the government’s success in creating visible, hard infrastructure – one of its undeniable success stories.

Even the road infrastructure within cities has improved substantially, with more flyovers and continuous widening of existing roads to accommodate growing numbers of cars, two-wheelers and three-wheelers, as more Indians now own private transportation. However, this breathless growth in road infrastructure has also aggravated the challenge of managing pedestrian traffic. Factors such as poor civic planning, rampant encroachment, corruption in municipal bodies, lack of driving etiquette and sheer apathy towards the woes of people have contributed to an alarming situation, where India records more road fatalities per capita than any other major country globally. And many thousands of them are pedestrians whose deaths account for nearly 20% of all road accident fatalities. This dubious distinction has raised alarm bells among policymakers.

Even the road infrastructure within cities has improved substantially, with more flyovers and continuous widening of existing roads to accommodate growing numbers of cars, two-wheelers and three-wheelers, as more Indians now own private transportation. However, this breathless growth in road infrastructure has also aggravated the challenge of managing pedestrian traffic. Factors such as poor civic planning, rampant encroachment, corruption in municipal bodies, lack of driving etiquette and sheer apathy towards the woes of people have contributed to an alarming situation, where India records more road fatalities per capita than any other major country globally. And many thousands of them are pedestrians whose deaths account for nearly 20% of all road accident fatalities. This dubious distinction has raised alarm bells among policymakers.

Nitin Gadkari, Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways, has highlighted this challenge on several occasions, even on the floor of the Parliament, calling it one of his biggest regrets and failures. Known for his no-holds-barred takedown of issues, he argued that most road accidents “happen in the country due to small civil mistakes, faulty DPRs and nobody is held accountable.” He points out that our road signage and marking systems are very poor. “We need to learn from countries like Spain, Austria and Switzerland. This gives me a feeling that basically, the engineers are responsible for increasing road accidents. So, the main problem is road engineering and defective planning, and defective DPRs,” he said. However, condemnation and self-reflection won’t suffice anymore as the Supreme Court has stepped in.

Nitin Gadkari, Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways, has highlighted this challenge on several occasions, even on the floor of the Parliament, calling it one of his biggest regrets and failures. Known for his no-holds-barred takedown of issues, he argued that most road accidents “happen in the country due to small civil mistakes, faulty DPRs and nobody is held accountable.” He points out that our road signage and marking systems are very poor. “We need to learn from countries like Spain, Austria and Switzerland. This gives me a feeling that basically, the engineers are responsible for increasing road accidents. So, the main problem is road engineering and defective planning, and defective DPRs,” he said. However, condemnation and self-reflection won’t suffice anymore as the Supreme Court has stepped in.

Supreme Court Weighs In!

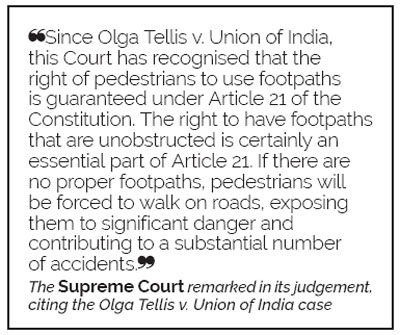

In a hard-hitting judgement with far-reaching consequences, the apex court has noted that citizens have a fundamental right to use footpaths without obstruction, linking it to Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life. The Supreme Court remarked that safe and obstruction-free access to pathways and sidewalks is a basic necessity, not a luxury! This timely judgement comes in the backdrop of a rising number of road fatalities due to the lack of safe access to walkable footpaths. In its judgement, the SC has ordered state governments and union territories to make footpaths safe, universally accessible and inclusive, especially for the elderly, physically disadvantaged and visually impaired.

Among its multiple directives on the matter, the SC questioned the government’s inability to establish the National Road Safety Board, mandated under the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019. The court said that it won’t tolerate any further delays, granting a final extension to complete the formalities. The apex court also instructed state governments and union territories to establish guidelines on footpath design and maintenance in a time-bound manner, asking them to focus on creating inclusive infrastructure for the differently-abled.

It also came down heavily on policymakers’ inability to decongest roads and directed authorities to free pedestrian roads from illegal encroachment and obstructions. The court also asked policymakers to ensure that urban planning laws are followed in letter and spirit to deter re-encroachment.

Can We Take a Leaf Out of the World’s Best?

Well-travelled Indians would know that some of the world’s best cities have first-class infrastructure designed to encourage pedestrian movement. Walking by the cobbled bylanes of Scotland or Japan’s Tokyo or Kyoto that value urban pedestrian-mobility is a hassle-free experience. More importantly, they are designed to ease commute for their citizens. That tourists benefit from such arrangements is an add-on that further encourages these cities to focus on delivering world-class pedestrian mobility.

Then there are other examples. Take, for instance, the Netherlands. As the gold standard for creating pedestrian infrastructure, its cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam have enabled pedestrian movement by creating Woonerf or living streets. These streets are well-lit and equipped with signals, and prioritise walkers and cyclists. To create an environment for pedestrian movement, they are dotted with benches and trees to reduce vehicular speeds. The Netherlands’ success is not a fluke. It is a culmination of decades-long public planning and efforts to create awareness by prioritising pedestrians over motorised vehicles. The secret to their success lies in car-free zones, imposing heavy parking fees to deter traffic and strict speed limits to create confidence among pedestrians.

Copenhagen is another city celebrated for its public-centric design. For the uninitiated, Strøget, located in the city centre, is one of the world’s longest pedestrian streets. It was established in the early 1960s, creating a template for other cities to follow. Copenhagen features ample green spaces, mixed traffic zones with strict speed limits, encouraging walking and cycling. Beautiful lighting, public art and benches enable walkers to travel considerable distances with ease.

Could India emulate a similar model? It most certainly could. The successes of these cities worldwide as leaders in non-motorised mobility demonstrate political will, a people-first design, integrated mobility systems and rigorous policy enforcement. Steep fines and proactive public participation act as deterrents, enabling policymakers to keep pedestrian and non-motorised mobility at the centre of their city planning initiatives. India could start small, perhaps by focusing on key areas in each city, such as the Aerocity and Connaught Place in the capital, Delhi. Both tourists and citizens frequent these commercial hubs. They also offer seamless metro connectivity and ample parking spaces to encourage non-motorised commuting. Policymakers could use the learning and data to evolve their strategies for a city-wide implementation.

Either way, any such initiative would require public participation, backed by solid last-mile connectivity. It is a multi-faceted puzzle and the clock is ticking. Among the many suggestions, some even advise privatising municipal corporations to free them from political interference. Will our state governments and union territories get their act together? Time will tell.